This story originally appeared on Inc.

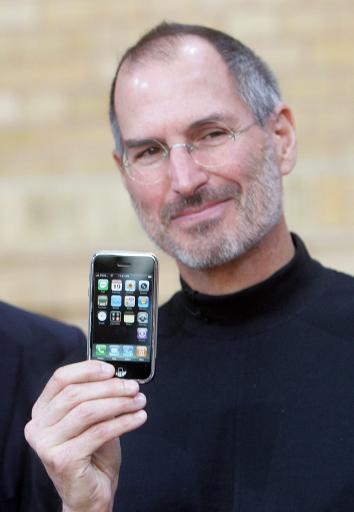

Steve Jobs, the late Apple co-founder and CEO, was a master businessman and showman. His way of combining apparent simplicity with an unrelenting demand for quality turned Apple into a giant.

He also knew how to use the media—for better or worse. Under Jobs, Apple honed the fine art of playing reporters and editors, timing information releases, and withholding stories to punish those who wouldn’t cooperate. Some of these tactics were models of how to smartly work with the press. Others were ethically suspect at best. Given the well-publicized history of Good Steve/Bad Steve, the man that could alternately inspire and then terrify employees, that should be no surprise.

Here are half a dozen techniques that Apple, under Jobs, regularly used to get its message out. Whether good or bad—and sometimes it’s all how you use things—each can be effective. Even if you don’t want to use them all, keep your eyes open because your competitors might, and recognizing what a rival is doing can be powerful.

Be Secretive.

Apple was one of the most secretive companies on the planet under Jobs. Not only was there great discipline about who was allowed to say what, but the company put into place what was described to me by some who would know as one of the most draconian and restrictive nondisclosure agreements the industry has ever seen. Apple reportedly has a Worldwide Loyalty Team that tracks down sources of unauthorized information leaks.

Forgetting the heavy-handed tactics for a moment, the impulse to be secretive is brilliant. Much of the press thrives on breaking news, which is a relative of that little thrill most people can get telling friends something juicy they hadn’t previously heard.

Now, many in the media who thrive on this sort of hard-news jones would love to think you have something that would interest their audiences (and potentially advance their careers). Being secretive without anything behind it will go nowhere. You need the right balance. An artificial air of mystery will get laughed down. On the other hand, telling everyone everything you’re doing is wearing on the listeners. Try just keeping developments secret until you’re ready to release the details. That way you also avoid alerting competitors.

Pick Your Favorites.

There were news outlets and particular reporters that Apple and Jobs liked. Walt Mossberg when he was at the Wall Street Journal, for example. John Gruber, of the blog Daring Fireball, was always another well-sourced writer. But Jobs wasn’t looking for fawning from this cadre. He found smart writers who got what he was trying to do and would appreciate it, then he and the company deepened the relationships.

Not even Apple could sweet talk the entire press, but it’s helpful to find sympathetic listeners who can help explain what you’re trying to communicate.

There’s a second type of favorite: reporters who long for insider access and the chance for scoops. They don’t have the same kind of loyalty, but will likely be more sympathetic in coverage for fear of losing the insider access that, to them, is a personal competitive career advantage. Mind you, not all reporters who excel in the art of the scoop are like this. Some are just good at building relationships and will write what they want, not what you want.

Punish Those Who Don’t Cooperate.

Apple and Jobs could get heavy-handed when it came to bad press, which meant stories that not only didn’t emphasize the Apple songbook but said things the company didn’t want to be public. One weapon was to cut off access to information, which puts beat reporters at a competitive disadvantage since rival outlets would have stories first. Or Apple might release a story that would contradict a reporter and make him or her look sloppy.

This is a dangerous tactic. It takes muscle and importance to make the punishment even noticeable, and it’s also a great way to make enemies that might suddenly become sympathetic to one of your competitors.

Learn How to Leak.

Much of Apple’s ability to push the press was through controlled leaks. A former Apple manager, John Martellaro, has written about how the company engineers a controlled leak of information. The short version is that upper management goes to a lower-level person, asks who they have good connections with in the press, and tells them to “idly mention this information and suggest that if it were published, that would be nice.” Nothing goes into writing (including emails) so there’s no way to track the planted story back to its source.

Planted stories can help companies judge public reaction on a feature, price point, or potential strategy; panic competitors; or even get analysts and influencers more interested in an upcoming product announcement event.

Plant Disinformation.

This is the fancy term for pragmatic lying. Using a controlled leak to a favorite journalist (see how these techniques build on each other?), or even having someone in management make an outright statement, the company says something that’s either blatantly untrue or highly misleading. A classic example was when Jobs declared that Apple wasn’t working on a mobile phone. That statement may have put competitors at ease, giving Jobs more maneuvering room. Another example may have been the repeated rumors that Verizon would finally get the iPhone, long before it actually did, which had the effect of slowing at least some talk about Android.

Perfect Your Presentations.

In marketing and PR, showmanship is everything. Any presentation has to be perfect—smooth, coherent, and compelling. That’s true for any presentation from a new product announcement to an onstage interview at a conference. Journalists often lose their more critical edge when things flow along without a hiccup to wake them up and get them thinking again.

Have Something Worth Writing About.

This is the biggest trick. All of the above media techniques suggest that the press wants to talk to you. You need to give them a reason. Create products and services in hot demand from customers, and you’ll find that more journalists want to talk to you.