In 2013, Ohio State University President E. Gordon Gee earned $6,057,615. This, according to the Chronicle of Higher Education, made him the top paid public college leader in the country—one of nine to break the $1 million mark. Much of that haul, it should be said, came from built-up deferred compensation and severance; Gee retired from his post last summer after he was caught on tape disparaging Notre Dame and Catholics. (He’s now running West Virginia University). But his $851,000 base salary was also the highest among state school leaders.

In the meantime, about 59 percent of Ohio State students now graduate with student loans. Of those who do, the average burden is about $26,000. And to top it off, according to a new report by the Institute for Policy Studies, between 2010 and 2012, debt among OSU students grew 23 percent faster than the national average.

So Gee got paid, while his students paid up. Should you be mad?

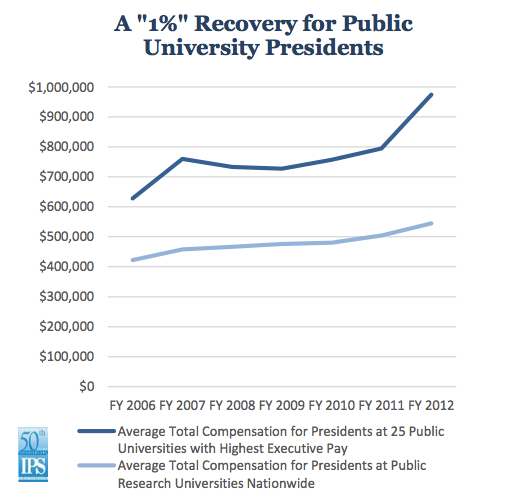

The Institute for Policy Studies thinks you should. Its report argues that a group of public colleges is showering its top administrators with money, while shortchanging spending on faculty and financial aid. At the 25 state universities with the best paid executives, it notes, student debt grew faster than at the average state school. Compensation packages at those institutions also grew far quicker than at public colleges on the whole.

(One note: The IPS appears to be revising its report due to problems with its data on faculty compensation, but that doesn’t affect the part we’re discussing.)

Of course, a single president’s salary, no matter how generous, isn’t going to influence tuition at a massive university. According to the Chronicle, Ohio State spent $4.5 billion last year, making Gee’s pay little more than a budgetary rounding error. But deluxe pay packages are a useful symbol for a much bigger issue that’s contributing to the skyrocketing cost of college—the growth of administrative expenses, which, as the Delta Cost Project has shown, have largely eaten away at whatever savings schools have managed to find by switching to adjunct professors. The IPS study notes that among the top 25 states with the highest executive compensation, spending on nonacademic administration—basically, anything that doesn’t directly touch students, like HR, legal operations, public relations, development, and the like—grew 65 percent. According to Delta Cost, public research universities have increased their compensation spending both on a per-student and per-employee basis.

Which has me beginning to wonder if we aren’t witnessing a new twist on Baumol’s cost disease—the fearsome malady that is often blamed for the expense of college today. Here’s the idea behind Baumol’s: In industries where productivity lags behind the overall economy, costs go up very quickly, because educated workers—even if they’re not producing much more than in the past—expect their pay to keep up roughly with their peers in other businesses. Otherwise, they’ll go and find another line of work.

The classic example is a string quartet. It takes the same number of people to play Mozart live as it did in 1900, but musicians expect a far higher standard of living, so the relative price of attending a classical concert has gone up. A similar explanation is often used to explain the price of college—professors still stand around in the middle of a seminar room and teach to the same 12 students they did in 1950, but are theoretically paid better for it. Colleges have managed to save costs on instruction by turning to adjuncts, which is why it doesn’t seem that Baumol’s is really the main culprit behind rising tuition.

But I do wonder if Baumol’s can at least help explain the growth of administrative bloat. As schools bring on more admin staff, some of whom might otherwise be working in the private sector, the cost of keeping a campus running is probably going to rise. And in a way, richly paid presidents might be the ultimate example. After all, those boards of trustees who set pay are often made up of VIPs from the corporate world, who may use the private sector as their frame of reference. Schools aren’t getting more efficient, but some of their leaders are being paid as if they were. And that can be a little infuriating, especially when the tuition bill comes around.