These are agonizing times for small, private colleges. Enrollment is falling. Debts are rising. Tuition is high as it can go. And since the financial crisis, schools have been shuttering more often than normal.

Now, Moody’s Investor Service, which analyzes the credit worthiness of more than 500 public and private nonprofit colleges, is delivering this grim prognosis for the future.

“What we’re concerned about is the death spiral—this continuing downward momentum for some institutions,” analyst Susan Fitzgerald tells Bloomberg. “We will see more closures than in the past.”

And that, I will add, might be a very good thing.

Small private colleges aren’t necessarily nefarious institutions, but they’re not exactly the heroes of higher education either. For the moment, forget about elite schools Amherst or Wesleyan (they’re doing fine, anyway). Instead, consider places like Ashland University in Ohio, which Moody’s has called a default risk. These institutions often cater to iffy students and produce mediocre graduation rates. But because they don’t have much in the way of endowments, they tend to charge high tuition, and leave undergraduates saddled with debts that simply might not be worthwhile. When all the aid is factored in, attending Ashland still costs $21,000 a year, according to the Department of Education. Meanwhile, only 59 percent graduate after six years. And so, according to Payscale, it offers one of the lowest returns on investment of any college in the country.

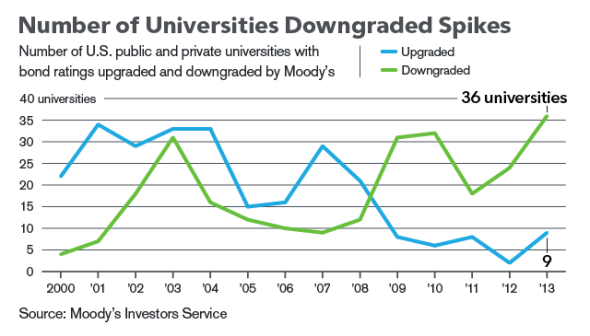

That might have been sustainable in a pre-Great Recession world. But as Moody’s has found, the business model of asking middling students to pay exorbitant prices for an education they might not finish is beginning to creak and fail. In part, that’s because many schools have larded themselves with debt in order to finance dubiously worthwhile expansions. But now that their enrollment rolls and tuition revenues are dwindling, their finances are fraying. In 2013, Moody’s downgraded its credit ratings on 36 schools and raised it on only nine. A study by Vanderbilt found that the rate of school closures doubled from about five annually before the crash to about 10 annually after it.

The Vanderbilt study is especially instructive because it shows the particular types of schools that have run into the worst financial strife. Again, they tend to be very small, with 1,000 students or under, and are often religiously affiliated. The majority of private nonprofit colleges, meanwhile, don’t really seem to be in too deep trouble. Overall, the sector’s enrollment has actually increased over the last few years. And while Bain has suggested that as much of a third of all colleges are on a financially “unsustainable” path, its metrics were a bit questionable (among other schools, it seemed to suggest Harvard and Cornell were in trouble. I assure you, they’re not).

What we’re witnessing right now, then, is a small brush fire, clearing out some of the unhealthier institutions in higher ed. It will be wrenching for the schools and the people who work for them. But hopefully, it will also inspire some better ways of doing business. A few colleges, like Ashland, have already responded by slashing their sticker prices. In practice, that often just means they’re handing out smaller aid packages, while charging about the same amount as always, but it’s a step in the right direction. If the demise of a few schools can make the rest of higher ed a bit healthier, then let the death spiral whirl.