What if the most accurate economic forecasts weren’t based on economists’ predictions, but on your tweets?

It might sound crazy, but a group of researchers at Stanford University and the University of Michigan genuinely believe that social media platforms like Twitter can add some valuable insight to economic projections. For more than two years now, these economists and computer scientists have been predicting initial jobless claims using an analysis of people’s tweets, and they think policymakers and market experts alike could take a leaf from their book.

The project, “University of Michigan Economic Indicators From Social Media,” is somewhat like Google’s Flu Trends map in how it works. Google tracks flu activity around the world by monitoring how many people are searching flu-related terms in different areas, and with what frequency. “We have found a close relationship between how many people search for flu-related topics and how many people actually have flu symptoms,” the search giant explains on its Flu Trends page. (Admittedly, the methodology of Flu Trends has come in for some criticism.)

Similarly, the researchers at Stanford and Michigan created their economic indicators by scanning billions of tweets for terms related to job changes, and analyzing those. For the moment, they’ve focused on predicting initial jobless claims because the actual figure comes out once a week, and it’s one of the simplest indicators to track among what people post on Twitter.

“We really wanted a number that was good enough that policy makers and market participants could actually use it,” says Michael Cafarella, one of the researchers on the project and a professor of computer science and engineering at the University of Michigan.

Cafarella says that the Twitter-based data is not a substitute for economists’ predictions, but he does believe that combining the two could make for more accurate forecasts. “If I were concerned with making the best possible predictions and my professional standing depended on it, I would want to use this data,” he says.

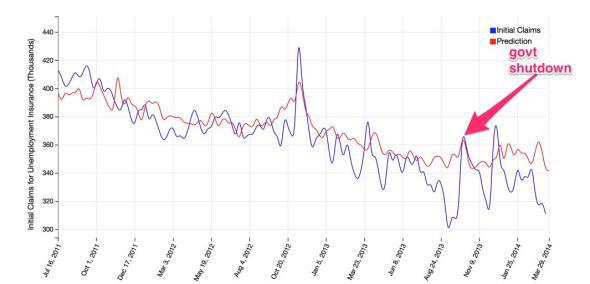

What’s more, he thinks the high-frequency, real-time nature of data from Twitter can add a valuable layer of analysis to more traditional methodology. This past October, for example, the economists noticed a small bump in their initial jobless claims data several days before the official government numbers came in, due to the as-it-happened impact of the government shutdown.

Courtesy of Michael Cafarella.

“The shutdown was a situation where you might be interested to see what was happening moment by moment, and we can provide that,” Cafarella explains.

The Twitter method has also succeeded in predicting, with some degree of accuracy, traffic at e-commerce sites (as a proxy for retail sales) and movie box-office sales. The researchers are looking at using it to collect data on mortgage refinancing and gas prices. For now, though, initial jobless claims is the main item on the agenda, so be careful what you tweet about unemployment—you might be skewing the data.