There are 3.8 million Americans who have been out of work for 27 weeks or more. These are the country’s long-term unemployed, as defined by the Department of Labor. And right now, they’re the subject of the most important ongoing argument about the state of the job market.

In recent months, a growing chorus of economists and writers have concluded that “the long-term jobless don’t matter to the economy,” as Wonkblog’s Ylan Mui put it in a recent headline. At least, they don’t when it comes to issues such as inflation and pay growth. (I’m guessing most everyone agrees that their personal suffering matters a great deal and that the world would generally be better off if they were working). The idea is that these unlucky millions are so far from employers’ radars, and so unlikely to ever hold a steady job again, that their presence no longer influences the rest of the labor market. Should the economy heat up, businesses will start paying out higher wages to keep or poach workers who already have jobs before they dip into the pool of people who have been out of the game for more than six months. And if wages escalate, so too could inflation.

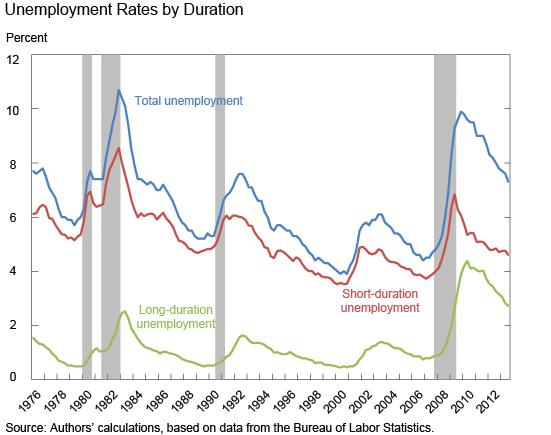

The Atlantic’s Matt O’Brien has dubbed the proponents of this argument “the new inflation hawks.” If they’re correct, the Federal Reserve may need to raise interest rates sooner rather than later to prevent prices from rising, even though it would cool down the economy while the long-term jobless are still struggling. The hawks note that short-term unemployment is roughly back to normal, and real hourly wages are inching up. Inflation, they say, could be just around the corner.

In other words: The Federal Reserve probably can’t help the long-term unemployed to begin with, nor should it risk trying.

So far, Fed Chair Janet Yellen isn’t buying the theory. “With respect to the issue of short-term unemployment, and its being more relevant for inflation and a better measure of the labor market, I’ve seen research along those lines,” she told reporters at a press conference Wednesday. “I think it would be tremendously premature to adopt any notion that says that that is an accurate read on either how inflation is determined or what constitutes slack in the labor market.”

Translation: Yellen isn’t ready to write off the long-term unemployed yet. And she may be holding out hope that those who’ve left the labor force altogether will one day return to the job hunt, too.

Yesterday, however, the hawks received a big intellectual boost, courtesy of a new paper debuted at Brookings by Princeton economist and Obama adviser Alan Krueger. It is a grim document, to say the least. Krueger and his co-authors, Princeton’s Judd Kramer and David Cho, suggest that many of the long-term unemployed may never work again and “tentatively conclude” that, as a group, they “exert relatively little pressure on the economy.” Wonkblog’s Mui has already written a solid summary, and the New York Times’ Binyamin Appelbaum has a very useful take. But here are three of the key points:*

1. The overall unemployment rate doesn’t seem to affect inflation. That depends on the short-term unemployment rate. Some economists have argued that the traditional relationship between unemployment and inflation, known as the Phillips curve, fell apart after the recession. But Krueger and his co-authors find that once you pull the long-term unemployed out of the equation and focus only on the short-term unemployed, it works again like new. The same goes for the relationship between wages and unemployment. But why? That brings us to …

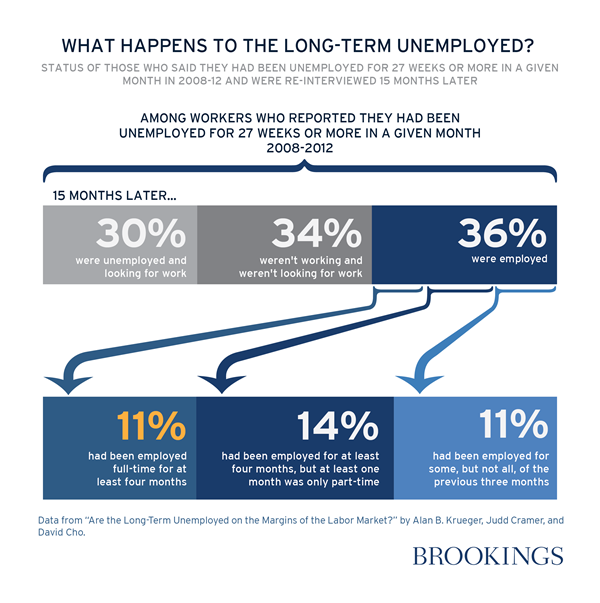

2. The long-term unemployed rarely return to work. Between 2008 and 2012, the authors found that, after 15 months, only 11 percent of the long-term unemployed were back in a full-time, steady job (as shown in the Brookings graphic below). This is in keeping with research that has found employers ignore job applicants who have been out of work for an extended period. But the problem may go deeper. The long-term unemployed, the authors write, seem to be on the margins of the labor market and have difficulty sustaining employment once they find it. Many ultimately lose interest in work altogether.

Graphic: Brookings

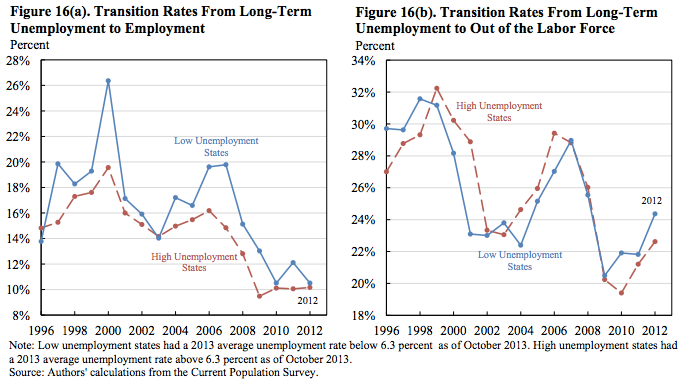

3. Worse yet, even a stronger economy might not help their predicament. The paper finds that the long-term unemployed don’t fare much better in states with low overall joblessness than they do in states with high overall joblessness. Regardless of the health of the local economy, they’re about equally likely to find a new job as they are to leave the labor force entirely.

Krueger & co. caution that “only time will tell” whether they are right about the relationship between wages, inflation, and employment. Still, the hawks are bound to cite their work as proof that the labor market really is tightening and that there is little the Federal Reserve can do for the long-term jobless.

I also doubt it will settle the argument. So for now, it’s worth remembering why the stakes of the debate are so high. We can all probably agree that Congress is not going to step in and do something dramatic to help the unemployed find work. That makes the Fed more or less their last hope. If it can’t help, or decides not to try, nobody will.

*Correction, March 21, 2014: This post originally misspelled the last name of New York Times reporter Binyamin Appelbaum.