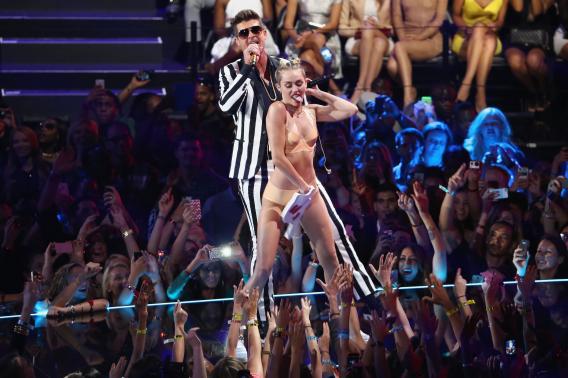

I don’t have any great Miley Cyrus angles for you this afternoon, but I have read a lot of people joking about how it’s weird that MTV still produces and airs an awards show about music videos even while it doesn’t broadcast any music videos. There’s actually nothing strange about this—the VMAs are exactly the sort of thing MTV should show and music videos aren’t. Once you understand why, you’ll have a better understanding of why BuzzFeed’s GIF listicles aren’t destroying American journalism.

The basic progression of a cable television network is to start with an idea that will cost very little money to execute and will obtain some nonzero quantity of viewers. Music videos are a great example. You have zero content acquisition costs. A great video is a great promotional vehicle for a band, so artists will literally give their content away. You need some programming specialists to decide what to air, and it’s nice to have some VJs around to improve watchability. But your costs are low low low low, and people will watch it. The problem here is that all the value is in the idea—the insight that people would watch this—and none is in the actual content. Realizing that people would watch a music video channel is hard. Starting a music video channel is easy. And once your music video channel is succeeding, the idea isn’t proprietary anymore. If you insist on continuing to fill your network with easily replicable commodity content, you’ll end up facing ruinous competition.

So a smart network does exactly what MTV’s done over the years. You take your audience demographics and your programming niche and you try to build more original less commoditized content around it. So Beavis and Butthead was a show built partially around music videos that appealed to MTVs demographic, but that was much less of a commodity. And then if you can succeed with Beavis and Butthead, why not Daria? And the VMAs are a great example of noncommodity programming.

Then MTV more and more pushed the commodity content onto MTV2, extending the brand. Now where MTV2 turns out to be a special case is that music videos are ideally programming for Web streaming, so eventually they fall off cable altogether. But you see the same thing with other channels. AMC’s original idea was to be a channel dedicated to showing classic movies. A totally sound idea, but a complete commodity content strategy. Mad Men and Breaking Bad and The Walking Dead, by contrast, are harder to repeat high-value plays. The Food Network has moved away from simple one-camera cooking shows to featuring more elaborate programming with more emphasis on production and editing, while the Cooking Channel has launched to air that discarded commodity stuff.

And you see the same thing in news media. In its early days, Slate was very heavy on pure aggregation. And aggregation was (and is) a good idea, but it’s easy to copy, so there’s no Today’s Papers or Other Magazines features anymore. Then along came Huffington Post with an aggregation-plus-sideboob content strategy that was going to ruin journalism. But in fact they went relentlessly upscale, built a big team that publishes tons of original reporting, and now they’re even doing long-form features. Next up was BuzzFeed with the GIFs and the listicles and that, too, was a good idea. But, again, the barriers to entry in that sort of thing are low, so BuzzFeed went out and hired reporters, and now you can read interviews with Rep. Jim Clyburn and reporting on congressional reactions to possible use of military force in Syria. Nobody succeeds by staying at the commodity level. Music videos are commodities; the VMAs aren’t. So a mature property like MTV will rightly be happier airing an awards show than hours worth of videos.