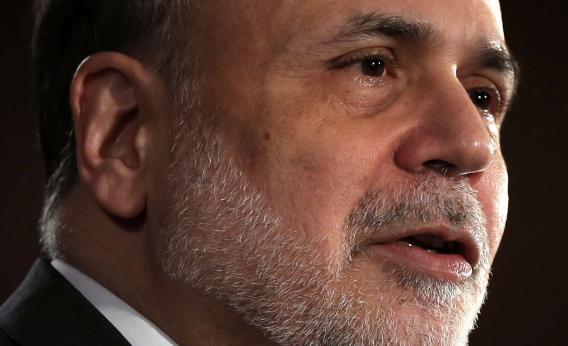

The idea of a “dual mandate” to pursue both price stability and maximum employment is that even if a pure look at inflation would lead the Fed to want tighter money, it ought to check out the employment situation and think twice before tightening if joblessness is widespread.* It’s looking this month, though, as if Ben Bernanke has a different view of what the dual mandate means. And that’s why we’re seeing headlines like “Weak economic data gives US stocks a lift.”

To understand why that would happen, you have to go back to the disastrous FOMC meeting and press conference that we had last week. I’m increasingly convinced that the problem there is that Bernanke seemed to roll out a curious dual mandate in which either rising inflation or falling unemployment would trigger tighter money.

That was the point of his criteria for “tapering” bond purchases. He said that if the economy improved enough, tapering would begin, and he said it even though inflation is low and inflation expectations were falling. It’s essentially a posture that looks at QE purchases as evil per se, and thus something to be halted in the face of good news even in the absence of inflation. The Evans Rule for interest rates embeds the dual mandate in the correct way, saying that mass unemployment will lead the Fed to temporarily ignore a bit of inflation. The taper criteria did the reverse, saying that good economic news means tighter money even if inflation is well-behaved. With that kind of dual mandate in place, bad news out of GDP revisions means tapering is less likely, which means the stock market rises. Meanwhile, we’re all left to cross our fingers and hope that the GDI number proves more accurate.

But a “bad news is good news” recovery can’t last for very long. What we need is a new statement from the chairman that good news is not bad news and there’s absolutely no chance of tighter money as long as inflation stays below target.

*Correction, June 27, 2013: An earlier version of this item misstated the Fed’s mandate as including “maximum unemployment” rather than maximum employment.