Paul Krugman’s column title today is “Profits Without Production,” which I think is right on, but a lot of his text ends up focusing on what I think is a side-issue of alleged monopoly rents:

Since profits are high while borrowing costs are low, why aren’t we seeing a boom in business investment? And, no, investment isn’t depressed because President Obama has hurt the feelings of business leaders or because they’re terrified by the prospect of universal health insurance.

Well, there’s no puzzle here if rising profits reflect rents, not returns on investment. A monopolist can, after all, be highly profitable yet see no good reason to expand its productive capacity. And Apple again provides a case in point: It is hugely profitable, yet it’s sitting on a giant pile of cash, which it evidently sees no need to reinvest in its business.

The problem here is that Apple isn’t a monopolist in any conventional sense. The vast majority of personal computer owners do not own a Macintosh. The vast majority of smartphone owners do not own an iPhone. The iPad does have a (contested) majority of the tablet market, but this is a rapidly growing market and Apple most definitely is seeking to expand its productive capacity.

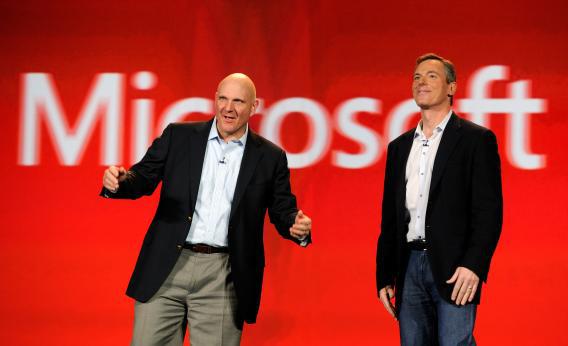

I would point to two different issues. One is that Steve Ballmer or Tim Cook can’t exactly get his executive team together and say “interest rates are low, let’s go buy $20 billion worth of innovative new product categories” in the same way that Southwest Airlines can decide to go buy a bunch of new planes. If you want to “invest” in growth, all you can do is buy whole companies, and that’s exactly what’s happening. But it’s also not obvious to me that Apple or Microsoft or Google actually is facing low interest rates. The relevant interest rate for investment decision purposes is the real interest rate, and computer-intensive firms are making investment decisions in a strongly deflationary environment. Even at Apple’s super-low nominal borrowing costs, the real interest rate involved in building a server farm might be astronomical.

In theory, this is what we have a banking sector for. Apple can make profits selling smartphones and then the banking system reallocates those funds to different firms who have promising investment opportunities—Apple doesn’t need to invest its own profits for the profits to recycle through the system.