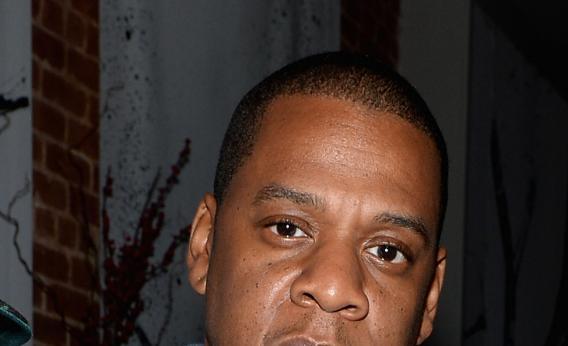

Jay-Z’s forthcoming album Magna Carta Holy Grail will be a big event for the music world, but it’s also an interesting business arrangement that could point toward the future of content—hardware subsidizing software.

The specific arrangement is that Samsung has pre-purchased 1 million copies of the album at $5 apiece, and in exchange, those million copies will be available to Samsung Galaxy owners for free download 72 hours ahead of the official release date. Or to put it in terms that are more appropriate to non-physical media, Samsung paid $5 million to the record company in exchange for authorization of 1 million early downloads of the song to high-end smartphone buyers.

This appears to have sparked some substantial backlash on the Internet, but the basic economics of the arrangement seem sound. The issue is that the marginal cost of distributing a cultural work is extremely low, but the fixed costs involved in creating one can be high. That can be because literally the thing is expensive to make (like reporting from inside Syria), or it can simply be because the labor involved demands a very high wage (which is presumably the case with Jay-Z). This makes content an ideal way of adding features to your hardware device.

Traditionally the way you see this is with software. If Apple tries to gain an edge over Samsung by putting some better components into the iPhone 5S, the problem is that each and every new iPhone 5S needs to carry the new better component with the higher costs that entails. By contrast, if Apple gains an edge over Samsung because people really love iOS 7, then a potentially infinite quantity of iPhones can take advantage of that at no additional cost. But the exact same logic that applies to gadgets and their operating systems also applies to other kinds of cultural content. People use phones and tablets to visit websites, read books, watch TV shows, and listen to songs. If there were certain sites, shows, books, and music that were exclusive to a particular hardware brand, that would be a competitive advantage that scaled up in a beneficial way. So you could imagine a future version of the music industry in which there are no record labels, just music divisions of device manufacturing who try to sign up the most appealing artists for their customers.

This Jay-Z deal isn’t nearly as far-reaching as all that, but it’s a step in that direction. Right now if you want to use iOS you need to buy an iPhone. In the future, it could be that if you want to listen to Jay-Z, you need to buy a Galaxy. But the backlash is a reminder that in the culture industry, efficiency does not always triumph. Concerts tend to sell out, for example, rather than potentially alienating fans with sky-high prices.