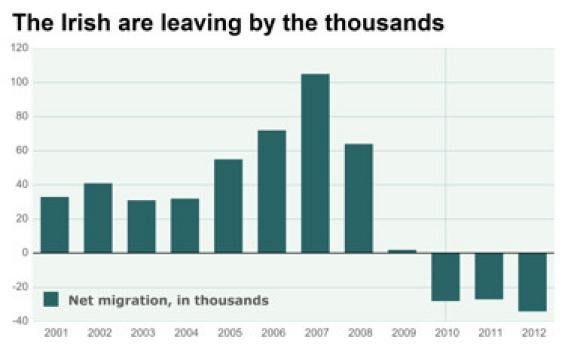

If economies can’t adjust to shocks through currency movements, having the people move instead works. And it’s happening:

A study by Real Instituto Elcano in February showed 70% of Spaniards under 30 have considered moving abroad. Portugal has seen 2% of its population leave in the past two years. The numbers leaving every year has doubled since 2008. A record 3,000 people are leaving Ireland every month, the highest level since the famine of the 19th-century. Some of them are Poles going home, but many of them are Irish.

Not surprisingly, a lot of them are moving to Germany. More than a million migrants moved to Germany last year, according to the Federal Statistics office, a rise of 13% from a year earlier. The number of immigrants coming from Spain, Greece, Portugal and Italy has risen by between 40% and 45% compared to 2012. But others are heading to wherever they have traditionally found work: Britain for the Irish, South America for the Spanish, and the U.S. for the Italians.

You can take this as a sign of how badly things have gotten, but I was speaking to an EU official earlier today who very much saw this process as a key part of the solution. To him, Europe’s lack of internal labor mobility compared with the United States isn’t just a fact of life to live with; it’s something the EU ought to be actively trying to address. Of course you’re not going to find a quick policy fix to the fact that Portuguese people don’t speak Finnish. But there’s a fair amount that could still be done to promote a single labor market in terms of things like pension portability and occupational licensing. Progress on those fronts would be a poor substitute for flexible exchange rates, but unlike flexible exchange rates it wouldn’t run contrary to the core political commitments of the continent.