I wrote yesterday about how the Principle of Seriousness helps maintain the true path of BipartisanThink by ensuring that no matter how unreasonable the GOP becomes on fiscal issues, neither party is proposing serious solutions because the GOP is being intransigent and the Democrats are failing to come up with proposals that stand a chance of overcoming GOP intransigence.

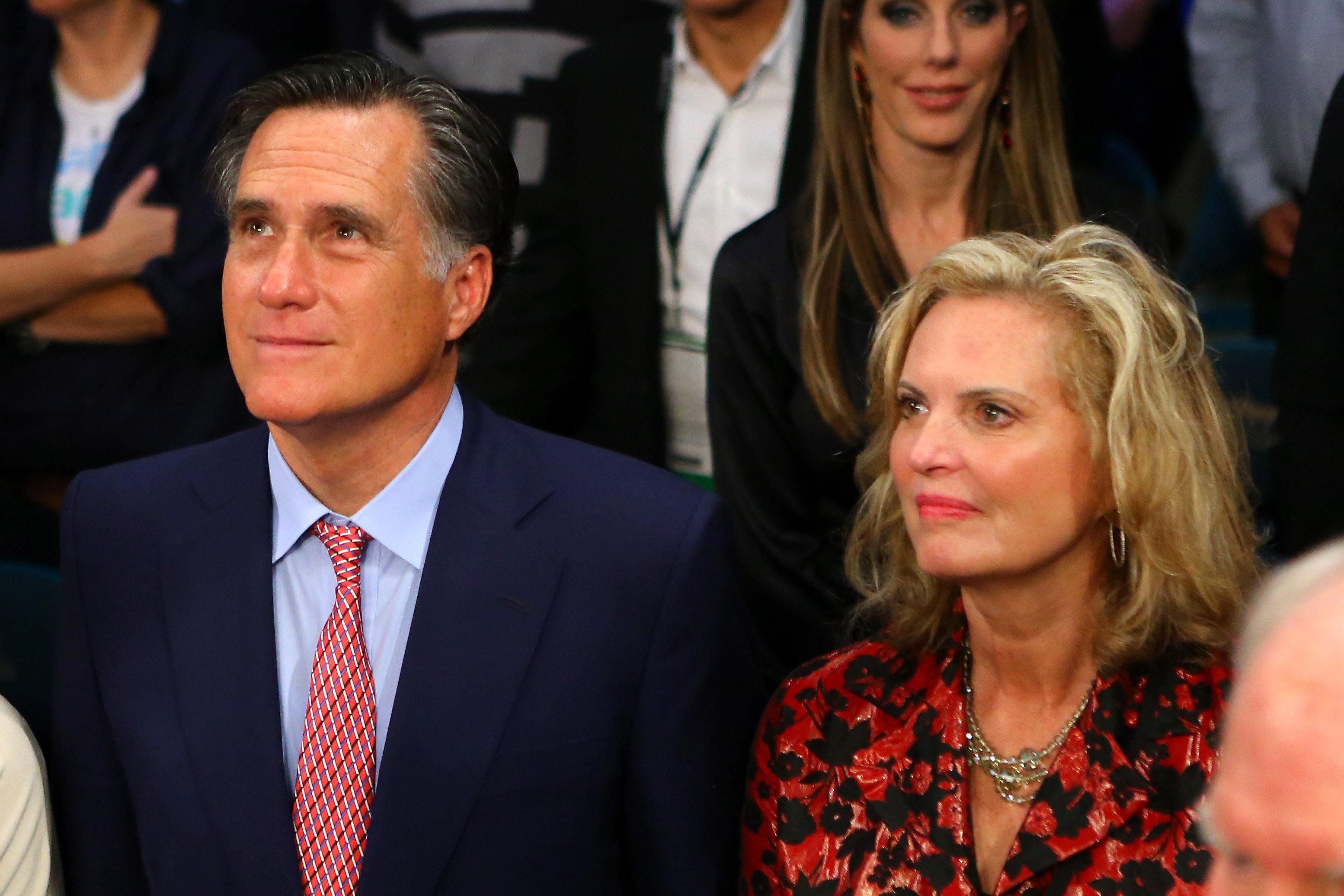

Josh Kraushaar in National Journal takes a more imaginative stab at maintaining BipartisanThink on sequestration by trying to ponder how a Romney administration would handle the situation:

More importantly, a close look at the composition of both the Senate and the House suggest the numbers would be there for Romney to pass some combination of spending cuts and the closing of tax loopholes, as he called for in the 2012 campaign. In the Senate, Romney probably would have courted the 12 red-state Senate Democrats, six who are up for re-election in 2014, to support some type of compromise. In the House, his task would be winning over recalcitrant conservatives. If House Democrats were united in opposition, he could afford 17 GOP defections, probably more if the few remaining moderate Democrats joined with the GOP.

That seems correct to me. If President Romney had wanted to replace sequestration with a mix of spending cuts and revenue-raising tax loophole eliminations, he would have found majority support in both houses of congress for it. But then Kraushaar takes the BipartisanThink turn by saying that what this thought experiment shows is that Obama is to blame for the current impasse because he’s failed to adopt this Romney-style approach. Missing from that analysis is that Republicans have clearly and repeatedly stated that they don’t favor raising even $1 of net tax revenue by eliminating loopholes and deductions. Their view is that taxes are high enough in the United States of America, and that any revenue raised by eliminating deductions should finance reductions in tax rates.

That’s the line Paul Ryan took when he served on the Simpson-Bowles commission, it’s the line John Boehner stuck to in the 2011 debt ceiling negotiations, it’s the line the GOP members of the Supercommittee adhered to, it’s the platform Mitt Romney ran for president on, and it’s not something they’ve waivered from since the election.

The reason the hypothetical works is that the premise of the hypothetical is that the leader of the Republican Party comes out in favor of more tax revenue! That really would lead to a deal if Romney ere in the White House. But if Boehner came out in favor of more tax revenue this afternoon, that would also lead to a deal. Probably Mitch McConnell could get the same deal sealed if he wanted to. What’s changing here, however, isn’t the attitude of the president it’s the attitude of the Republican Party. But they really don’t want to raise taxes. They’re quite sincere about it. And whether you agree with them or not about this, it’s their deep-seated desire to keep taxes low that makes fiscal compromise impossible.