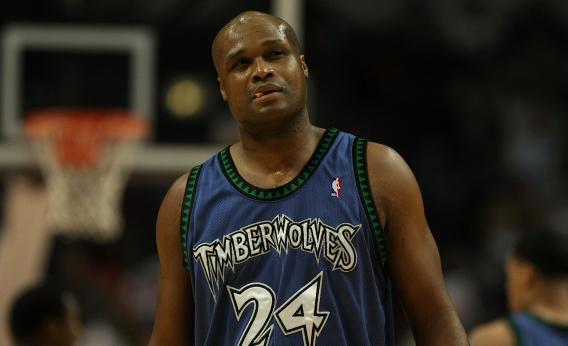

Antoine Walker, who earned a ton of money as an NBA player but ended up bankrupt anyway, is now trying to dispense financial advice to other players. It’s a worthy cause, but I think doomed to failure. The nature of professional basketball is that it puts a ton of money into the hands of guys who aren’t of an age where you’d expect to see a lot of financial planning, who don’t come from social networks that are savvy about business, and who face a lot of social pressure to be big spenders.

The good news is that they have a union and a collective bargaining agreement and in principle you could rejigger the basic framework of the contracts to improve the outcomes here.

In a normal work arrangement the way it works is that you get a paycheck every week or two until you’re gone. Part of the reason it works that way is that you might quit or get fired with very short notice. But NBA contracts don’t have that kind of flexibility. Kevin Durant can’t just “quit” and go work for the Clippers instead and the Knicks can’t just fire Amare Stoudemire and decide they don’t want to pay him. Consequently, there’s no reason that the pace of the financial payout has to match the duration of the labor contract. You could pay the players all the money up front and then just have them be obligated for four or five years. That, obviously, would make the savings problem worse. So you could do the reverse.

Establish something like a flat $500,000 per year salary for every player. Then any financial compensation a player receives over $500,000 has to come in the form of an annuity—a fixed annual payout every year for the rest of your life. A player who’s more in-demand will get offered a larger annuity than a player whose services are less-demanded. A player who’s willing to commit himself to playing for five years will get a bigger annuity than one who wants to become a free agent after two years. You’d have to rejigger the mechanics of the salary cap, but the same basic concepts could all carry over.

For the players, this would mean financial security. But what’s more, since the rule would apply to all of the players it would make it easier to stick with financial discipline. At any level of income it must be very difficult to try to be a prudent saver if all your peers are spending like crazy. You want to keep up with the Joneses. But if all the rookies are limited to $500,000 a year and even veterans with accumulated annuities aren’t spending that much more, then it’s easy to be happy with the mix of a generous stipend and a promise of life-long financial security. The handful of players who get giant endorsement deals would still have financial windfalls, of course, but that’s not the median player and even they will always have their annuities to fall back on.