I’m a card carrying fully paid up member of the human capital sect of the neoliberal tribe. I think that doing everything we can—from lead abatement to nurse home visits to pre-K to K-12 school reform to funding community colleges to pushing the boundaries of online higher education to fighting summer learning loss—is the most important thing we can do to bolster American prosperity over the long term.

Unfortunately, some other people have let their passion for this issue plunge them into confusing the long-term virtues of skill-building and education with short-term labor market problems. Bill Clinton took that plunge briefly last night, alluding to the idea that some of America’s unemployment is being caused by the fact that workers don’t have the “right” skills for today’s jobs.

There’s a lot of good empirical work out there (see this earlier this summer from the Chicago Fed for example) indicating that this isn’t the case, but I think it’s worth running through the theory here a bit.

The basic reason that you should be skeptical of the idea of a macro-consequential level of skills mismatch in an economy that isn’t demand constrained is that it involves positing a gigantic and somewhat baffling market failure. As of ten years ago there was basically nobody in the United States who was trained to explain smartphone features to potential customers in retail stores. But thanks to the invention of the Blackberry, the iPhone, and the rise of Android there’s been a surge in demand for workers who can sell smartphones and smartphone plans in AT&T, Verizon, Sprint, and T-Mobile stores. In response to this, the relevant firms have done the sensible thing and trained people to do the job. The economy wouldn’t make any forward progress ever if firms couldn’t hire workers without the workers first obtaining the relevant skills—nobody ever would have been able to bring a smartphone to market, so workers wouldn’t have known that the skills were even something a person could learn. Employer reluctance to invest in worker training (and worker reluctance to invest in their own training) is evidence of weak demand not an alternative to weak demand.

What’s often going on here is a kind of fallacy. You look at unemployment by education level and find that more-educated workers have a lower unemployment rate. You then reason that if everyone had a college degree, the unemployment rate would be much lower.

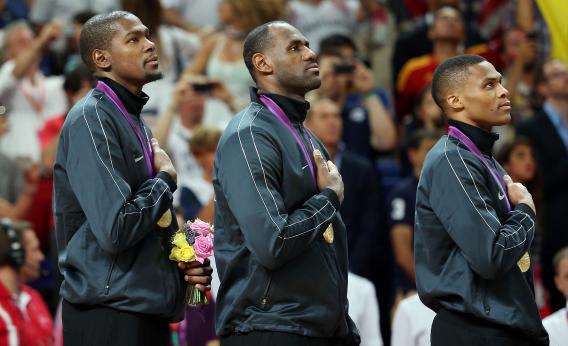

This doesn’t follow. Employment in the lucrative NBA sector is highly correlated with height. But if the average height of the American male increased by two inches, there would be no surge in NBA employment. The aggregate quantity of NBA employment is jointly determined by the audience demand for NBA games and the carteling behavior of the league owners and the NBAPL. Skill at basketball is a major determinant of whether any particular person gets an NBA job, but the level of NBA employment is about demand and labor market regulation.

And I think this helps us see where skills-mismatch does occur. I’ve never heard of an unemployed surgeon. Demand for qualified medical doctors is extremely high. Somewhat bizarrely we simply didn’t increase the number of slots in medical school for three decades:

So skills-mismatch isn’t impossible. It’s real, even. Just look at the doctors. But you need some specific explanation of how the market could fail that badly. The supply of people legally permitted to practice medicine is restricted by law so even if demand for doctors grows we don’t see more doctor-training. This is a totally legitimate problem to concern yourself with. But it’s clearly not the case that the difference between full employment and mass unemployment is a vast shortage of doctors.