The scary thing about JPMorgan’s recently multibillion-dollar loss in Fail Whale betting isn’t just the size of the losses, it’s the CEO’s response. If Jamie Dimon were prepared to go out there and say that this was all part of a perfectly sound strategy and that a sound strategy simply entails losses sometimes, that would be one thing. But his view of the bank he runs is that it lost billions of dollars on a bad strategy that was badly implemented and that where we should go from here is that he’ll keep running the bank like this:

In the years leading up to JPMorgan Chase’s $2 billion trading loss, risk managers and some senior investment bankers raised concerns that the bank was making increasingly large investments involving complex trades that were hard to understand. But even as the size of the bets climbed steadily, these former employees say, their concerns about the dangers were ignored or dismissed.

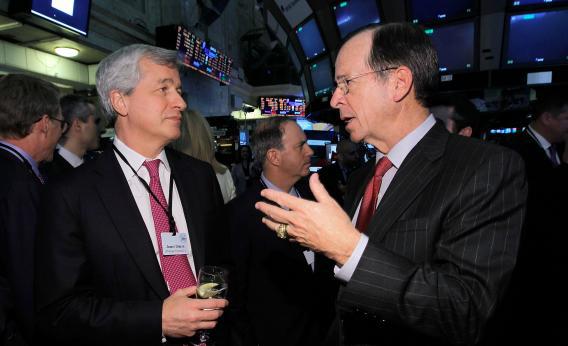

An increased appetite for such trades had the approval of the upper echelons of the bank, including Jamie Dimon, the chief executive, current and former employees said.

But I do think it’s crucial to shift the attention somewhat off the question of stopping banks from making poorly managed risky bets and on to the question of what happens when they bet themselves into bankruptcy. Contrary to myth, there’s no such thing as a “small enough to fail” depository institutions in the United States nor are small banks immune to terrible decisions and bankrupting themselves. But what happens is that in the FDIC resolution process the depositors get the overwhelming majority of their money back, the stockholders get nothing, and the managers get fired. It’s not a costless outcome and it doesn’t replace the need for prudential regulation, but the basic functioning of the system doesn’t rely on the prudential regulation being perfect; it relies on the FDIC resolution process halting panics without propping up shareholders and managers.

Dodd-Frank is supposed to create a similar process for dealing with bigger, more diversified institutions and the success or failure of the bill ultimately stands on the success or failure of that part of it. JPMorgan and its peer institutions will keep being profitable on 99 days out of 100 and having trades blow up in their face on one day out of 100. Even if any given bank only blows up so big it becomes insolvent one day in 10,000, then in a world of multiple mega-banks that means at least one mega-bank blowup per decade. When they trade themselves into bankruptcy, will contagion be halted? And will it be halted with measures short of a bailout of all the people responsible for the bad trading? There’s some reason for optimism that Dodd-Frank has gotten this right, and there’s also some reason for doubt. But what happened at JPMorgan doesn’t yet shed much light on the issue.