Humans have a great instinct for nostalgia, so there seems to be a perennial taste for criticizing current arrangements with reference to the Good Old Days. Here, for example, is The American Prospect on Goldman Sachs and Wall Street:

At its best, Wall Street serves an important function. Historically, it provided the wherewithal for growth in industries as varied as rail and information technology; by bankrolling productive growth of industries that provided jobs and products to sell around the world, it vastly increased the well-being of all Americans. In times of crisis, bankers worked to preserve economic stability. Sometimes, they were genuine altruists, accepting the moral responsibilities that go along with their positions of wealth and power. More often, they were simply pursuing their own self-interest. Was J.P. Morgan a robber baron or the man who almost single-handedly saved the economy in the panic of 1907? The answer is both. But altruistic or not, bankers understood their enormous stake in the long-term vitality of the economy. Preserving the health of the economy was good for business this year and for decades to come. That was the contract between Main Street and Wall Street.

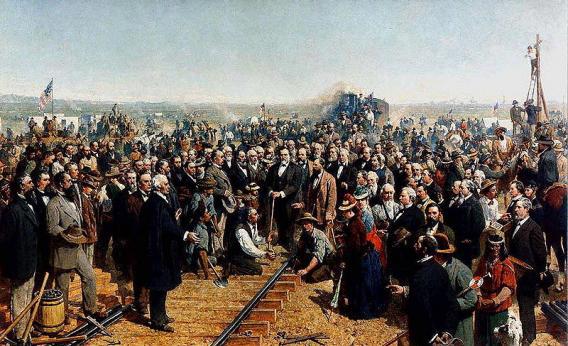

This is a wildly utopian account of Gilded Age finance*. I’d urge everyone to read Richard White’s Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America for a darker view. Michael Kazin’s review will help:

To gain an edge on their corporate rivals, railroad owners built expensive lines into drought-prone areas that had few settlers and little prospect of attracting more. To finance their risky endeavors, they routinely bribed politicians and borrowed money they could not pay back — while publishing mendacious financial reports. To insure friendly coverage, railroad executives bankrolled local newspapers and arranged to kill or delay the publication of stories that might damage their interests. […]

He views them as 19th-century equivalents of the profit-mad, short-sighted financiers who recently undermined economies on both sides of the Atlantic. Both transcontinental railroad managers then and the Wall Street bankers in our time ran “highly leveraged operations” that “depended on continued borrowing to meet their obligations.” Both groups made it rich because they had powerful enablers in Washington. In the 1870s and 1890s, when panicked investors dumped the heavily watered stock in their railroad portfolios, the market collapsed, and long depressions ensued. […]

Yet, in 1894, Cleveland’s attorney general, Richard Olney, rushed to court to bust a national strike by railroad workers who were expressing solidarity with a walkout by employees of the Pullman sleeping car company. With a federal injunction in hand, Cleveland ordered thousands of American troops to break the strike and arrest its leaders. At the time, the attorney general was on the payroll of at least one major railroad company.

As for “information technology,” I imagine most readers can remember for themselves the ridiculous business models, absurdities like the AOL/Time-Warner merger, the accounting scandals, and all the rest. The difference is that when time passes and the dust settles, Google is still standing and that’s what we remember. The transcontinental railroads were, among other things, an enormous engineering achievement that shaped the national economy. Some day folks living in Arizona are going to look back on the heroic days of rapid growth in Maricopa County and hail the developers and bankers who made it possible. We know it was a boondoggle, but to them it’ll just be home. I don’t want this to turn into an apologia for the bad practices or flawed institutions of today, but people should look toward a better tomorrow without getting all misty-eyed about the robber barons of the past. It’s long been the case that if you have large capital needs, one of the best ways to raise the funds is to get high-prestige, politically connected bankers to help you mislead investors about exactly what it is they’re signing up for.

* The age was “gilded” and not, as I originally wrote, “guilded.”