Former National Economic Council Chairman Lawrence Summers has a new op-ed out on the hot subject of inequality that I largely agree with, but that repeats a specific line about Kodak and Apple that I’ve heard from him before and I think is wrong:

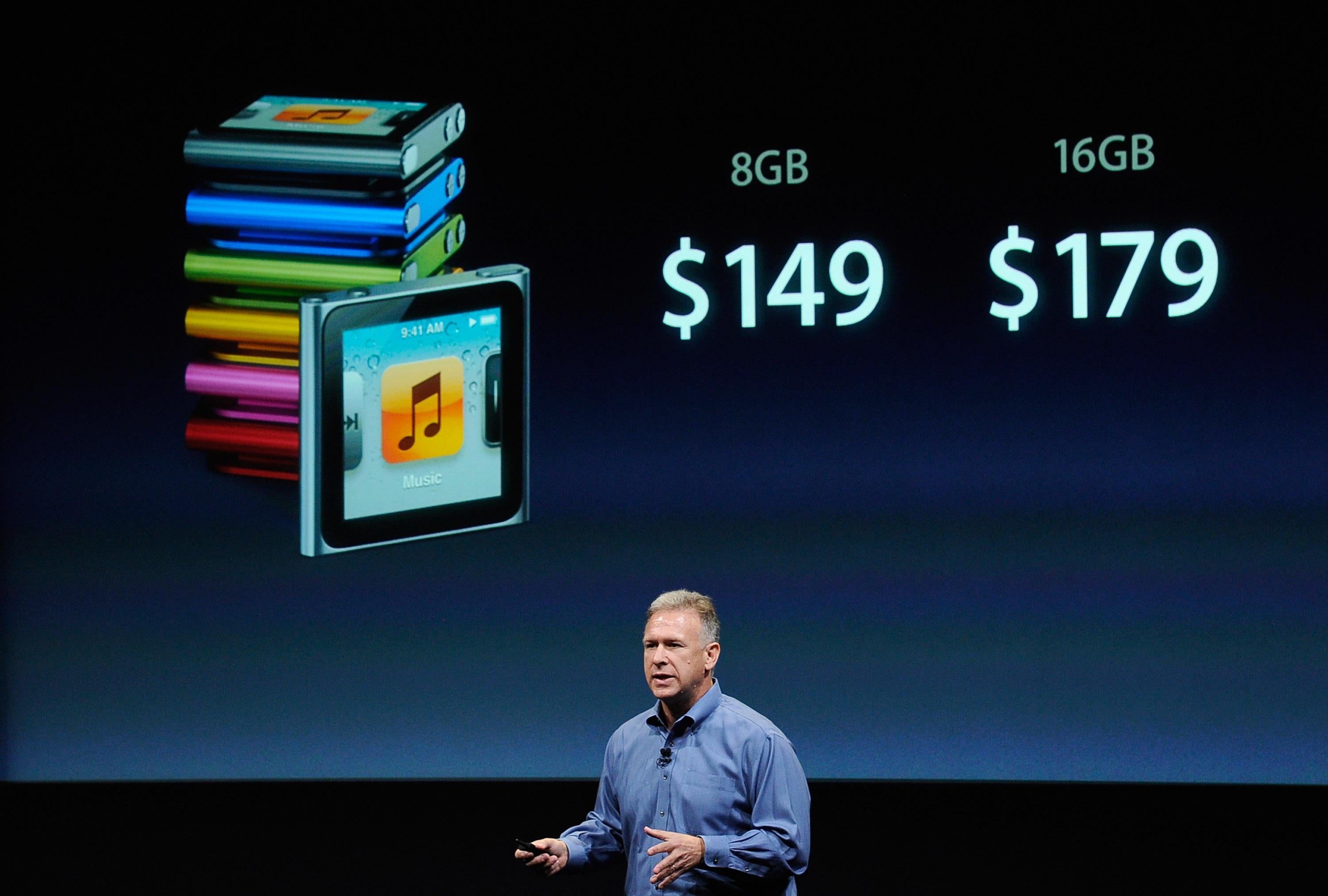

Why has the top 1 percent done so well relative to the rest? The answer lies substantially in changes in technology and in globalization. When George Eastman revolutionized photography, he did very well, and because he needed a large number of Americans to carry out his vision, the city of Rochester, N.Y., had a thriving middle class for two generations. When Steve Jobs revolutionized personal computing, he and Apple shareholders did very well, but those shareholders are all over the world, and a much smaller benefit flowed to middle-class American workers, both because production was outsourced and because the production of computers and software was not terribly labor-intensive.

The idea here is that the technological innovations of yore had broad benefits for the whole community in which they were produced, whereas todays innovations only serve a narrow elite of shareholders and a mass public of manufacturing workers in Shenzhen. The problem with this is that if you look median household income by metro area you’ll see that the San Jose MSA, home to Apple, is one of the richest in the country with a median household income of $85,267. That’s a median, not a mean, so it’s not like one of these things where Larry Page walks into a bar and suddenly the “average” person is a millionaire. The median household income in Silicon Valley is about $30,000 higher than in the country as a whole. Next door in the San Francisco MSA it’s $74,000. In Boston it’s $70,000. Just like in the days of yore, these centers of high tech entrepreneurship not only make fortunes for company founders, they’re breeding grounds for a strong and prosperous middle class.

The real differences from the Kodak era are twofold. One is that we arguably have fewer of these companies. America in 2011 has a few high-tech clusters, including the three names above and also Seattle, Austin, and arguably Washington DC. But we used to have dozens of cutting-edge manufacturing clusters. The other thing is that back in the day if you wanted to take advantage of the growth and prosperity in Rochester, you just had to go move to Rochester. Today, a working class person looking to get ahead by moving to the Bay Area is going to find that it’s prohibitively expensive to afford a reasonable place to live. Of America’s 15 highest-wage metro areas, all but Minneapolis feature exorbitant housing costs (it’s very cold in Minneapolis). That depresses real earnings and discourages efficient population migration. The policy shifts that have pushed housing costs through the roof in prosperous cities have more to do with the contrast than any particular feature of building cameras versus building computers.