Media outlets groaned at the “dad jokes” President Obama cracked at his final turkey pardon this Thanksgiving. In the runup to the election, BuzzFeed fawned over “how dad” vice presidential candidate Tim Kaine was. And as Hello Giggles giggled over the incident: “President Obama yelling at Bill Clinton to hurry up is the most dad thing that ever dadded.” We, or at least nostalgic Democrats, are having a major dad moment right now—and it might not just be signaling a change in our language, but also a change in our ideas about masculinity.

The Oxford English Dictionary dates “dad jokes” to 1987, citing a defense of the wince-inducing wit in a Gettysburg Times op-ed. The OED also finds “uncoordinated dad-dancing” in a 1996 Scottish Sunday paper. But dad has been proliferating in mainstream slang recently. Last year, we pedestaled the “dad bod.” This year, we bought up Steph Curry’s “dad shoes,” plain white sneakers that seem more at home mowing the lawn than driving the line. Men air-guitar a solo on their favorite “dadrock” hit or let their paunches hang out, arms akimbo, when assuming the “dad stance.” Loose-fitting “dad jeans” and beat-up “dad caps” are must-haves to pull off the fashionably uncool “dad style,” a trend some are dubbing “dadcore.”

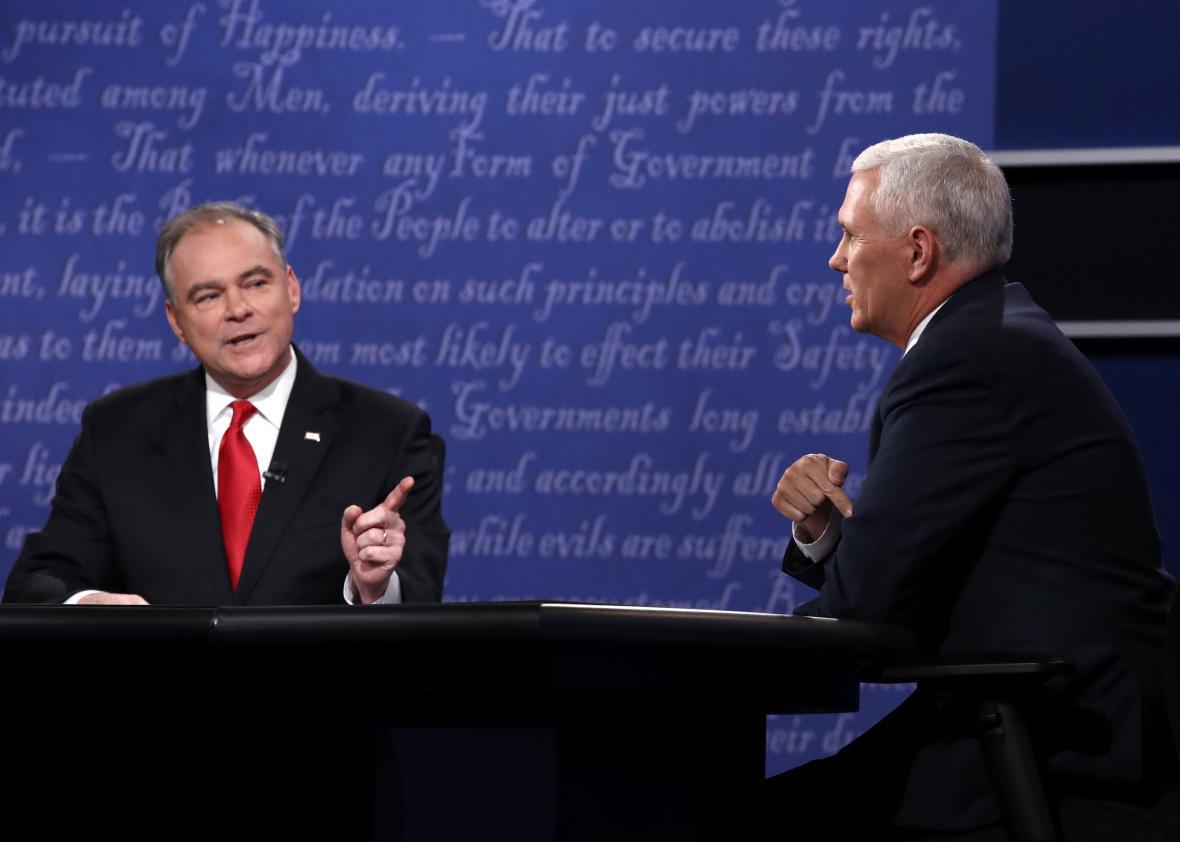

BuzzFeed has been further expanding the linguistic possibilities of dad. One listicle, “17 Pictures That Show Just How Dad Tim Kaine Is,” features the politician unabashedly grinning as he eats brunch, plays harmonica, and performs public duties with a contagious excitement. As the piece concludes: “It’s possible that Tim Kaine could be the most dad VP in American history.” (Slate would agree, if Kaine’s “dad gestures” are any measure). BuzzFeed has previously employed dad in this way. A 2015 quiz, for instance, asked “How Dad Are You Actually?” and invited readers to tick off a long list of stereotypic dadlike behaviors ranging from “Got to the airport five hours early” to “Talked about which road to use to get to a place.” Respondents then learned whether they were “not very dad” or “extremely dad.”

Elsewhere, dad has become an action. New Zealander and new father Jordan Watson created a popular YouTube series called “How to Dad” to help his fellow clueless paterfamilias. The Funny Beaver website touted Tactical Baby Gear’s dude-friendly products as “How to Dad Like a Boss.” And on social media, fathers have been proudly hashtagging their parenting with #dadding since at least 2010.

As lexicographers Emily Brewster and Ben Zimmer have observed, dad is undergoing a functional shift, or a change in its grammatical role. The informal dad begins as a baby’s-first-word noun, but the compound dad joke deploys it as a modifier, called an attributive noun, while the expression Tim Kaine could be the most dad transforms the word into a predicate adjective. To dad and be dadding, of course, turn dad into a verb. Grammar peevers often resist such shifts; consider the perennial handwringing over impact as a verb. But the English language thrives on repurposing its stock. Father, as an apt example, has been a verb since at least the early 1400s, while Shakespeare’s Duke of York famously quipped “uncle me no uncle” in Richard II. Dad is a novel instance of an age-old pattern.

But driving these linguistic shifts may be a broader cultural shift in the construction of masculinity. Dad doesn’t simply mean dad. #Dadding status updates typically look to a more active and equal model of parenting. The hashtag can punctuate a successful diaper-change as a Herculean feat, embracing the messy mundanity of parenthood as it self-deprecates male incompetence—and begins, ever so slowly, to acknowledge a deep and overdue debt to mothers.

What’s more, the expanded uses of dad are not limited to dads as such. A nondad can sport dad jeans just as a nonmom might mom jeans, and, as lexicographer Jane Solomon has noted of internet slang, we’re even addressing male figures we admire as dad in a form of fictive kinship. These dads celebrate a certain kind of male character. Dad jokes are cheesy and embarrassing, but endearingly so. Dad clothes are comfort-forward, not fashion-forward, but it’s hard to fault a man who owns his inner schlub. And the honesty and imperfection of the dad bod, moreover, are precisely why many find it attractive. Dad locates a positive, authentic maleness in the foibles and flab we associate with fathers and maps them onto the aging Average Joe. And being dad represents a frustrating but lovably dorky way of being in the world.

Dad, then, offers a refreshing alternative to modes of masculinity that have hogged our language in recent years. Bromance, brogrammer, and other bro- portmanteaus chest-bump with a fratty, six-packed, bong-ripping immaturity. Mansplaining, manspreading, and man- blends call out an arrogant and aggressive paternalism. But dad? It’s simple, practical, corny, and ultimately well-meaning. Just like, well, dads.