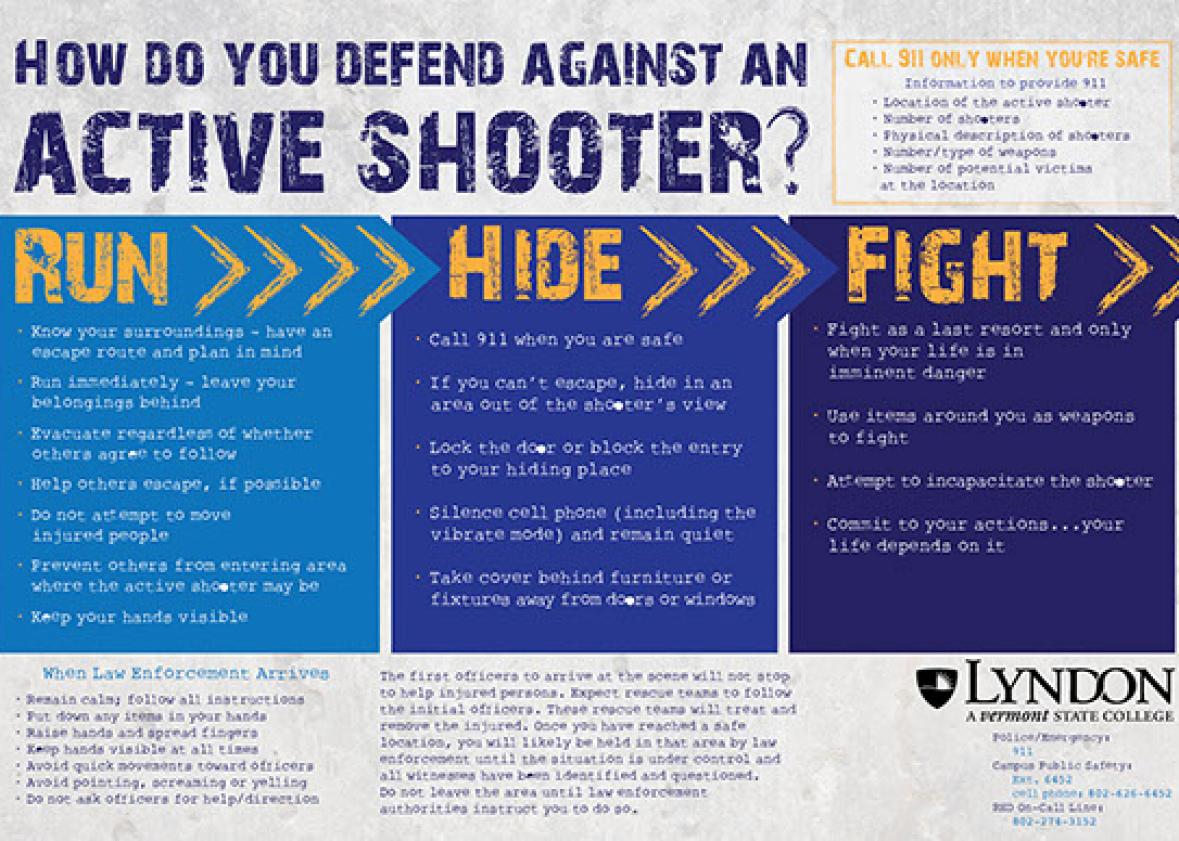

As a terrifying knife-attack scenario unfurled at Ohio State University on Monday morning, emergency services tweeted typical instructions to the student body: “Run Hide Fight.” This direction, regularly promoted by the FBI and Department of Homeland Security, is intended to ease the thought-processes of people confronted with imminent danger. The message is ostensibly simple: Run if you can, hide if you can’t, and fight if there’s no other option on the table. Easy enough, right?

Not exactly. While federal agencies treat “run, hide, fight” as protocol—it’s even laid out on the DHS’s official website—studies show that it’s not fully compatible with how our brains work. In moments of peril, our natural response may be to freeze, with thought and actions temporarily suspended. According to professor of science Joseph LeDoux, this instinct is part of our “predatory defense system” that extends to other mammals and vertebrates: “If you are freezing, you are less likely to be detected if the predator is far away, and if the predator is close by, you can postpone the attack.” Accordingly, even if running is the safest option, it’s not always a command that our brains can instantaneously put into practice.

Retired Lt. Col. Mike Wood adds that, aside from failing to address our “freeze” impulse, the word “run” suggests a linear path, which can be dangerous when split-second flexibility is required. He proposes an alternate three-word phrase to correct this problem: “Move, escape, or attack.”

The value of move relative to run is clear: It’s a command that more sharply contrasts with freezing. “Analysis and decision comes later, after the victim has helped himself by moving ‘off the X,’ ” Wood explains. “In training, the concepts of cover, concealment, and angular movement (instead of running straight away from the shooter) can be addressed in conjunction with the ‘move’ command.” The same line of thinking extends to the use of escape, which connotes the presence of a threat more clearly than hide, and of attack, which is unambiguously proactive and offensive, unlike “fight.”

Of course, this is about differences in how to respond to terror—there’s no one-size-fits-all policy for reaching safety, and thus, no ideal phrase to condition the masses with. As emergency physician Matthew D. Sztajnkrycer—who generally supports the use of “run, hide, fight”—puts it, “No one can tell us how we should or will act under these circumstances.” He’s right, in a sense: Humans may do what feels right and natural. Still, effective instruction might be able to change instinct for the better. Indeed, when every second matters, a stronger understanding of the relationship between words and our brain—between commands and impulses—could turn out to be a life-saving pursuit.