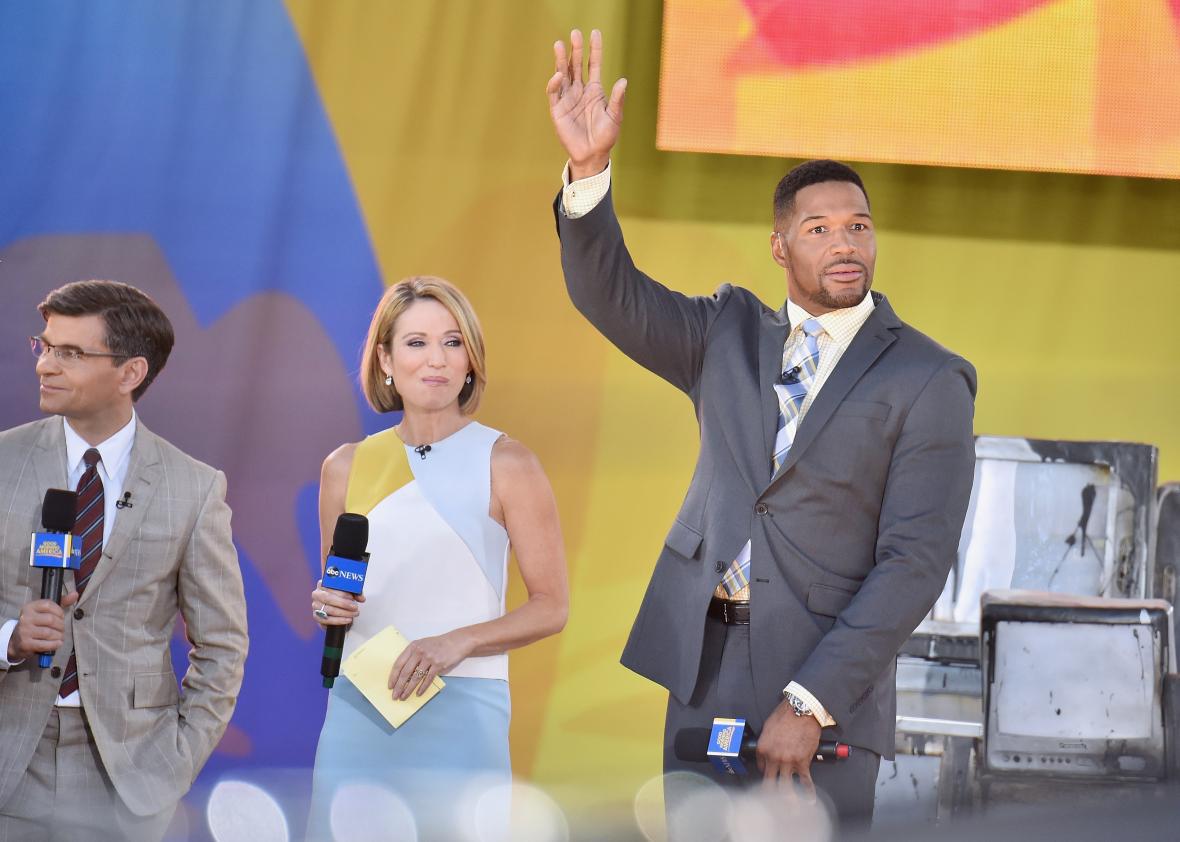

With Good Morning America’s Amy Robach currently on the griddle for referring to black people as “colored people,” some might understand that the term has long been archaic but quietly wonder just what was wrong with it.

After all, “person of color” is considered perfectly OK, and even modern. Since “colored person” means the same thing, why is it wrong to say it?

Some would say that black people have a right to decide what they want to be called, and that that’s all there is to it. However, that answer is incomplete, and risks people merely classifying the matter as one more example of what Steven Pinker has artfully called the “euphemism treadmill.” We can do better than that.

Not that there isn’t such a treadmill. It’s that tendency that can seem designed to annoy us—how terms for groups and policies, especially, often turn over every generation or so. Crippled became handicapped became disabled became differently abled. Home relief became welfare became cash assistance and temporary aid.

Indeed, the fact that a century ago colored and Negro were acceptable terms—such that even today we have the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the United Negro College Fund—is well known. In the ’60s, those terms were replaced by black; by the time I was a conscious person in the early ’70s Negro was already a term I associated with my mother’s older books, unthinkable in current language. Then after just 20 years or so, African-American became the “proper” term, with person of color coming in at the same time as a way of referring to nonwhite people. However, in practice, person of color is used more for brown people than, say, Asians, and among brown people, for most, person of color suggests a black person somewhat more readily than a Latino.

“So what do they want to be called now???” one might ask about black people, differently abled people, cognitively challenged people, and others. However, the rolling terminology is not based on willful petulance or a deliberate way of keeping other people off guard. It stems from the way euphemism works—or better, always starts to work but doesn’t.

Namely, a euphemism is designed to step around an unpleasant association. When it comes to societal terms, the idea is to rise above pejorative connotations that society has linked to the thing in question. Hence while cripple was once a perfectly civil term, negative associations accreted upon it like rust or gnats, such that handicapped was felt as a neutral-sounding innovation. However, after a time, that word was accreted in the same way, such that disabled felt more humane. Yet, as we have seen, even that didn’t last.

The lesson is that when there are negative associations with something or someone, periodic renewal of terminology is not a feint, but something to be expected. Until the thoughts or opinions in question change, we can expect the rust to settle in, the gnats to swarm back on—and the only solution, albeit eternally temporary, is to fashion a new term. Woke becomes the new politically correct. My bet is on hurtful to become the new offensive, as that word takes on an air of association with leftist argument.

This returns us to names for black Americans. Malcolm X didn’t spearhead a change from colored and Negro to black because he wanted to keep the white man on his toes, but because he felt that those terms had associations with evil, negativity, and more specifically slavery and Jim Crow. He wanted to start afresh with a more neutral and even muscular term—black, at the time, sounded what we would today call fierce, “woke” even. African-American was similar—there were always those on the sidelines who were suspicious of black as suggesting evil, obscurity, and the negative in comparison to the “purity” of white. African-American, suggesting a link with ancient and vibrant cultures, felt celebratory and positive to Jesse Jackson and many other people.

The rolling terminology, then, is an attempt to refashion thought, not to be annoying. What creates confusion in the present tense on the African-American terms, however, is two things.

First, colored was replaced not because it was processed as an insult but because of something subtler, its association with a bleak past. As such it can seem odd that anyone would treat someone’s slipping and saying the term as an insult, given that “Colored!” was never a slur in the way that a word I need not mention was and is.

Then second, in other cases of rolling terminology, the older terms do become processed as slurs. To call someone a cripple or retarded today is starkly contemptuous, redolent of the schoolyard, the drunken barstool, or vicious argument. However, that isn’t true as much of colored or Negro, which is why they are still allowed in the names of older organizations (as opposed to how icky Mark Twain’s characters’ use of the N-word feels today, occasioning endless discussion and discomfort). The N-word is so deeply offensive across time and space that it leaves little room for other words to create anything like its grievous injury.

Notably, black has persisted robustly alongside African-American—note how clumsy “African American Lives Matter” would seem. The reason is that despite the persistence of racism after the early ’70s, few could say that black people since then have lived under the bluntly discriminatory, life-stunting conditions that blighted all black lives then. As such, African-American didn’t have as much ugly thought to replace, which is why it always had a slight air of the stunt about it, always felt as a bit in quotation marks. Black never connoted the ugly-newsreel/segregated water-fountain pain of Negro and colored, and African-American was created not because black had become especially freighted with negative associations, but because the hyphenated conception of identity had become so attractive and in vogue at the time. I personally have always found African-American clumsy, confusing, and implying that black history since 1600 was somehow not worthy of founding an identity upon, and I only use it when necessary. Yet I would never have ventured this relatively idiosyncratic position about Negro and colored.

In the end, Robach experienced what we usually call a slip of the lip—“colored people” is a readily available flubbed version, in the heat of living speech, for people of color. More interesting, really, is the response to her slip. The reason “colored people” is offensive without being a term of abuse is that it reminds many people of times when we were, whatever we were being called, abused.