I predict that people commenting on this article will be dismissive, if not hostile.

What do I mean by that? Am I predicting that commenters will be dismissive, and possibly even hostile? Or am I predicting that commenters will be dismissive, but not to the point of being hostile?

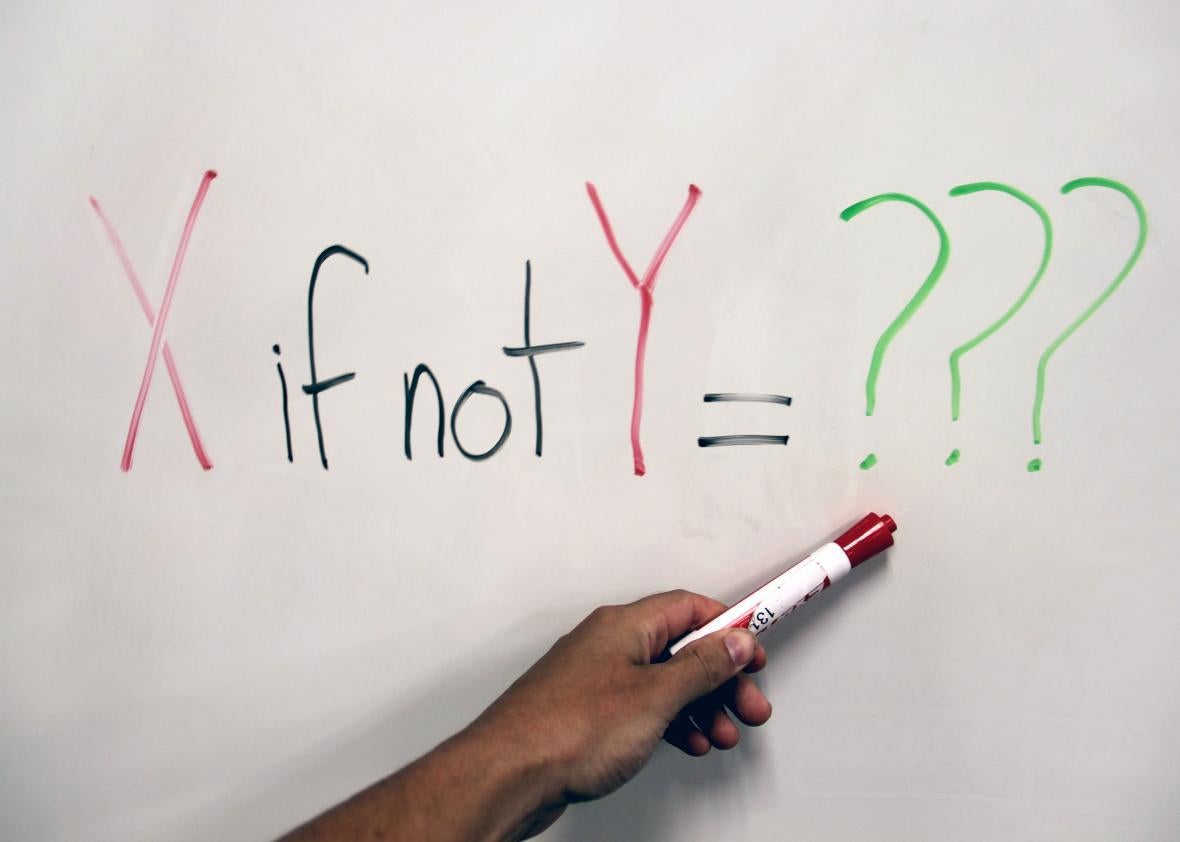

I ran a Twitter poll asking the same question, with different words:

The statistical insignificance of Twitter polls aside, anecdotal experiences as a journalist and educator lead me to believe that if you use the “it’s X, if not Y” formula in your writing, about half of your readers will think you mean one thing and half will think you mean the exact opposite.

Comprehension is at stake, so this is a language problem worth correcting, unlike the perfectly fine “I could care less” idiom, which almost everyone interprets the same way despite the fact that it literally means the opposite of how we use it.

With the “it’s X, if not Y” formula, ambiguity is built right into the word “if.” That conjunction exists to help us describe situations in which one thing might be the case, or another thing might be the case.

People in the “it’s X, if not Y = it’s X, but not Y” camp are presuming that you already know the answer to the question you’ve implied with your “if.” Take this example:

Many, if not all readers have already skipped to this article’s comment section to tell me I’m wrong.

My use of “if” in that sentence implies that there was — at some point — a possibility in my mind that all of you would have already skipped to the comment section before you got this far. However, there are context clues that would lead you to believe I had already considered and dismissed that possibility before writing my sentence; clues such as the unlikelihood that I would write and seek publication of words that I sincerely believed no one would read.

In contrast, people in the “it’s X, if not Y = it’s X, and maybe Y” camp are taking my sentence more literally; they think I’m saying there’s a possibility that all of you have already skipped to the comments, but in the event that some of you haven’t, certainly many of you have.

Both of these interpretations of my sentence are defensible, which means it’s a bad sentence. If two equally intelligent and informed people can come to opposite conclusions about what you mean, then it’s time to rephrase.

You should never write that something is “X, if not Y.” But you should feel free to say that out loud.

It’s easy to communicate which of these two options is your intended meaning by using inflection. However, it is impossible to render that inflection in text without using non-English characters or symbols, because the difference is tonal, not emphatic. For example, try reading this out loud implying one meaning and then the other:

The problem with writing nitpicking articles about language is that most of the time, if not every time, somebody will point out a language problem in your article, which damages your credibility.

If you wanted to communicate that something happens most of the time, but not every time, you’d emphasize the word “every.” If you wanted to communicate that something happens most of the time, and possibly every time, you’d also emphasize the word “every,” but with a different tone. In common English, we can indicate emphasis in text with italics or ALL CAPS, but we have nothing to indicate tonality (or do we?).

The solution here is simple: When dealing in text, write that things are either “X, but not Y,” or “X, and perhaps Y,” instead of “X, if not Y.”

I expect that one, and perhaps more of you will point out in the comments that I’m not the first person to make this argument. However, I think I am one of the first, and perhaps the first to do so using this many prismatic, self-referential examples. I’m nothing if not precious.

(Wait, does that mean I actually am nothing? My god, I’m vanishi—)