Assassination, bedazzled, lonely, rant, scuffle, zany: These are just a few of the 1,700 words we traditionally credit to Shakespeare. Some, like elbow, seem like they should have always existed in the English language; others, such as swagger, feel strikingly modern. Perhaps these words, acts of inspired creation from a godlike artist, let us glimpse the genius still gripping us 400 years since he last put quill to parchment. Or perhaps we’re looking for his linguistic prodigy in the wrong place.

For one thing, we can’t say for certain that Shakespeare actually “invented” these words. Even the Oxford English Dictionary, the definitive record of the English language, only documents the earliest written evidence it finds for a word. Shakespeare may simply have been the first person to put down in writing the words we attribute to him. Or he might have been cribbing from older texts that didn’t survive.

Also, the English language was in violent flux when Shakespeare was writing. The Renaissance flooded English with new words, especially Latin and Greek loanwords for the new and burgeoning discoveries, ideas, and creations of the time. In response, some purists and romantics reached back to the Anglo-Saxon word-hoard for their linguistic inspiration. Beyond its seismic semantics, English was experiencing tremendous internal upheaval in its pronunciation, grammar, and spelling. Shakespeare didn’t simply pull new words out of a vacuum: He was drawing from a environment already electric with linguistic innovation and change.

Perhaps we should locate Shakespeare’s linguistic genius in one of the oldest and most productive means of word formation: compounding. Put simply, a compound makes a new word out of two existing ones. Some are simple nouns or modifiers, like rainbow or fast-acting; others are more grammatically complex, like never-before-seen. (If we study some of the words attributed to Shakespeare, we’ll actually see this process of compounding at work, e.g., bedroom and eyeball.)

Shakespeare seized upon the inherent creative energies of English compounding and transformed them into art. Examples abound throughout his oeuvre, but King Lear shines an especially bright spotlight on his combinatorial craft. In this tragedy, as the aging former monarch descends into madness, Shakespeare’s language explodes with compounds, as if requiring a new vocabulary to describe the depths of Lear’s despair.

First, we behold Lear’s “compounding” rage. He agonizes over one daughter’s “sharp-toothed unkindness” and wills the “fen-sucked fogs” to foul her. After another daughter also repudiates him, Lear offers his submission to “hot-blooded France” and invokes the “Thunder-bearer,” “high-judging Jove.” These adjectival compounds lend a vivid imagery and strident music to Lear’s indignation. (They also drape their nouns in the grandeur of the Homeric epithet.)

Next, we learn of nature’s “compounding” wildness. A gentleman reports that a raving Lear is out roving a desolate, storm-struck heath, where he strives “in his little world of man to out-scorn/ The to-and-fro-conflicting wind and rain” from which even the “cub-drawn bear” and “belly-pinched wolf” seek shelter. Lear is only accompanied by his loyal fool, “who labors to out-jest/ His heart-struck injuries.” “Out-scorn,” “out-jest,” and “to-and-fro-conflicting,” featuring verbal and adverbial compounding, mirror the extremity and the commotion of the storm—and the king.

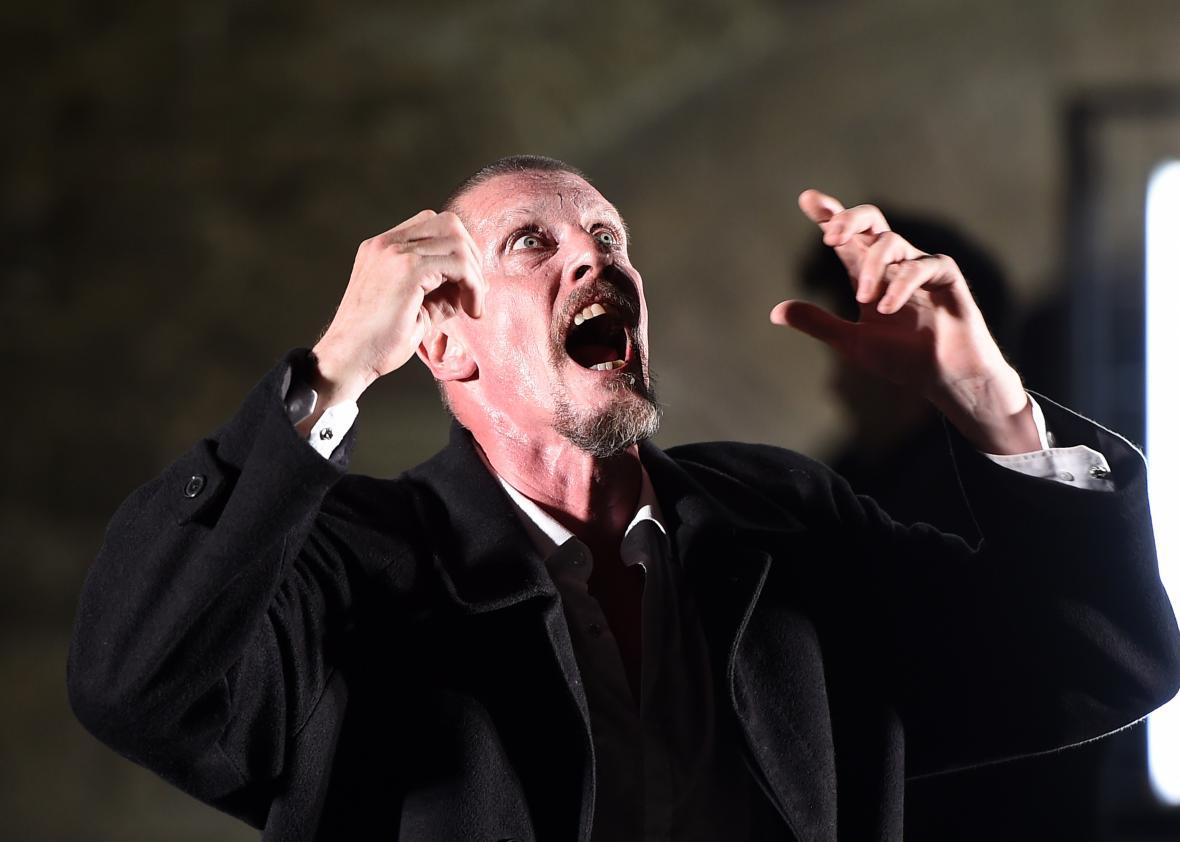

Then, we witness Lear’s climactic madness:

You sulphurous and thought-executing fires,

Vaunt-couriers to oak-cleaving thunderbolts,

Singe my white head! And though, all-shaking thunder,

Smite the flat the thick rotundity o’ the world!

Amid the forceful modifiers of “oak-cleaving” and “all-shaking” are the “thought-executing” “vaunt-couriers”: lightning bolts.

Elsewhere from Lear’s vortical agony, whirlwinds are “star-blasting,” nights are “hell-black,” ungrateful daughters are “dog-hearted,” bastards are “half-blooded,” cowards are “milk-livered,” traitors are “toad-spotted,” and fortunes are “fire-new.” All these compounds, of course, have descriptive power. They conjure up a visceral imagery to match the intense events of this tragedy, if not give figure to the ineffable emotions its characters experience.

But Shakespeare’s compounds also have a dramatic power: In them, language becomes a site where the thematic concerns of the play are contested. King Lear collides parent and child, king and servant, man and god, man and nature, young and old, wise and foolish, sane and mad, seeing and blind. Shakespeare stages these conflicts in his very compounds, crashing words together in his storm of language. These compounds aren’t mere words: They are theater.