Prince’s sudden and shocking death last week prompted an outpouring of responses on social media, with one particularly widespread commemoration taking the form of the quote: “Good night, sweet prince.” While the words make for a pithy and tender remembrance, you’ll agree, if you’re familiar with the source of the saying, that they simply call up the wrong prince for Prince.

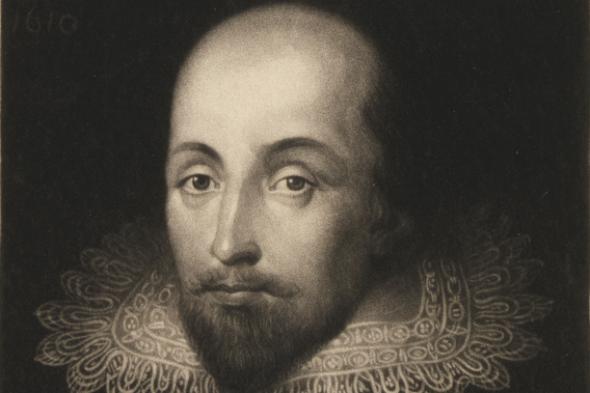

Another genius gave us “Good night, sweet prince”: William Shakespeare, who also died at a tragically young age, 52, at least by our modern standards. Like Prince, Shakespeare was an artistic polymath, writing, performing, and producing many of his works. The phrase appears in Hamlet, which features such hits as “to be or not to be,” “infinite jest,” “the lady doth protest too much,” “to sleep, perchance to dream,” “something is rotten in the state of Denmark,” and “words, words, words.” These lines, and many more, have become so ingrained in the English language that it’s as if they’ve always existed. We can forget Shakespeare even wrote them, just as many of us were surprised to learn Prince, aside from his own hits, authored the Bangles classic “Manic Monday.”

Most of these Hamlet hits are spoken, in the epic guitar solo that is the Shakespearean soliloquy, by the play’s title character. But not, of course, “Good night, sweet prince.” Spoiler alert: After Hamlet dies in the final scene’s bloodbath, his friend Horatio offers: “Now cracks a noble heart. Good night, sweet prince,/ And flights of angels sing thee to thy rest—” (Hamlet 5.2.302-03). These are tender lines, and mellifluous, too. But I think we are hanging too much on surface similarities in this passage.

For Hamlet was pensive, hesitant, melancholy, and—OK, surveillant may characterize Prince’s absence from YouTube. I certainly can’t speak to Prince as a person; privately, he may well have embodied the Danish prince’s intense introspection. But as an artist and performer, Prince is quite unlike Hamlet. For one, Prince would have cut at least four chart-topping albums by the time Hamlet actually manages to avenge his father’s murder.

That’s why I’m proposing a new “Tweeitaph” for Prince: “Now comes in the sweetest morsel of the night, and we must hence and leave it unpicked” (2 Henry IV 2.4.336-37). These words come from Shakespeare’s second most studied character: the hilarious fat knight Falstaff, who lovably thieves, sleazes, and boozes around with Prince Harry, the madcap prince who later becomes the ideal English monarch, Henry V.

First, let’s take the context of the lines. Falstaff doesn’t issue these words to Prince Harry; he says them after Harry, called back to the court, bids Falstaff good night. The moment marks a death, of sorts, for the next time Harry, newly crowned and reformed of his debauched ways, meets Falstaff, he rejects his old friend. I don’t mean to imply Prince treated his friends this way, of course; I’m only pointing out that Falstaff’s “sweetest morsel” ends up being a kind of farewell.

Second, the content. Harry and his companions have just finished up partying. After food and drink, Falstaff turns his attention to that “sweetest morsel of the night”: sex. Prince would approve of the sensual and decadent imagery. His lyrics were lascivious, his image erotic, his hourslong live performances tantric, and his prolific creativity never leaving anything “unpicked.”

Finally, the character. While Falstaff doesn’t say his words to Harry, his “sweetest morsel” serves as an indirect answer and address to the youth, who has just offered his goodbyes and exited the scene. And this prince is precisely the Shakespearean prince we should be invoking to honor the Purple One. Hal, like Prince, was a virtuoso of self-invention.

In Henry IV ,Part 1, we see heir-apparent Harry reveling with common drunks, thieves, and whores in London’s seedy taverns and dangerous highways. Later, we see him defeat his rebel counterpart, Hotspur, on the battlefield. In Henry IV, Part 2, we see him finally spend some time in the royal court. Harry is in complete control of his own conduct. Early in Part 1, he makes his actions quite plain:

I know you [his companions] all, and will a while uphold

The unyoked humour of your idleness.

Yet herein will I imitate the sun,

Who doth permit the base contagious clouds

To smother up his beauty from the world,

That when please again to be himself,

Being wanted he may be more wondered at

Breaking through the foul and ugly mists

Of vapours that did seem to strangle him. (1.1.173-81)

(Again, focus on the presentation and creation of self, not Harry’s base use of his friends.)

Through the two-part history, the royal Harry speaks like his lowly tavern mates, practices the hotheaded dialect of rebel, and tries on the language of his father (even literally trying on his crown when Henry IV is sick in bed). It’s as if he manages to become great by amalgamating all of these registers into something completely original, ultimately rendering him a more experienced and rounded ruler when he is coronated Henry V. So, too, did the genre-bending and gender-bending Prince master—and transform—many musical languages, exercising complete control over his identity as he continuously reinvented himself.

Prince was too funky, sexy, dynamic, alive, and self-styled to be remembered as the “sweet prince,” a paranoid procrastinator with a morbid streak. So, let’s “hence” to the afterparty and not leave the “sweetest morsel of the night”—in whatever the pleasure takes—go “unpicked.”

Then again, the Shakespeare maven among us will note that Horatio actually cuts himself off when he says, “Good night, sweet prince,/ And flights of angels sing thee to thy rest—.” As the em-dash indicates, Horatio suddenly switches his topic, asking “Why does the drum come hither?” The drums announce another prince, Fortinbras of Norway. If you insist on turning to Horatio’s “sweet prince” to bid your farewell to Prince, just make those drums play a really sweet beat.

Text quoted from The Norton Shakespeare (1997, W.W. Norton, ed. Stephen Greenblatt).