Everywhere we go online, we are tempted. We are tempted to click, tempted to watch, and tempted to argue. Maybe most of all, we’re tempted to support websites and decisions that reflect the internet’s democratic ideal, and we’re tempted to reject ones that are inherently antidemocratic. This is, ultimately, why most people seem thrilled that the AP Stylebook now says it’ll lowercase the internet and the web.

I support the decision on web—it’s a nickname and a useful prefix—but for the internet, we should realize this glee for what it is: an emotional response to symbolism that feels right, and a confirmation of what we do naturally. When we write online, most of us rarely bother to use the shift key; capitalizing anything is more work than it’s worth, and much of the text we search and communicate with online remains uniformly lowercased. Words are words; who cares about the window dressing? Even when we do cap as a rule or in formal writing, many lowercase the internet as a matter of habit and history, as the New Republic’s Adam Nathaniel Peck recounted last July. The stylebook’s reasoning is a usage one: Lots of people don’t cap it, so we’re cool with not capping it.

But there’s irony in changing a rule simply to follow a trend: By reversing a decade-plus policy of capitalizing internet, the stylebook is damning itself; it’s ensuring that thousands of old articles that cap internet will look dated. (It also makes me wonder whether the high-profile switch is simply a flashy attempt to sell new, “up-to-date” AP Stylebooks.)

If we’re to have standards for capping anything, it makes sense to cap the Internet. We capitalize nouns when specific ones are absolutely singular. Kanye West, Oklahoma, Lake Shore Drive, Hamilton, Saturn, Glengarry Glen Ross … all of these deserve caps because they are extremely specific, individual entities. With apologies to Mark Joseph Stern, this reasoning also helps explain why the AP Stylebook lowercases the court when referring to the Supreme Court. Unlike the Supreme Court, there are many other courts that we’d reasonably refer to as the court—but we’d never refer to other saturns, or Yeezus forbid, other kanyes. There simply is no other Internet. There’s the dark web, and there are lower intranets. But there’s only one specific place where Google searches; where Slate lives; where Instagram changes its algorithm; and where we waste Saturday afternoons sating our desires on Tinder, Yik Yak, and Cornhub. It’s one place as proper and unique as Saturn. And it’s utterly reasonable to capitalize this realm’s name.

Styleguides are important for establishing consistency across a single publication. They clarify language and help give readers a sense of stability. But when standards become malleable based on usage alone, they start to lose their power.

The AP Stylebook is venerable in part because it’s committed to saying that there are standards, and for providing a steady hand for publications looking for an authority on how and why to stay consistent.

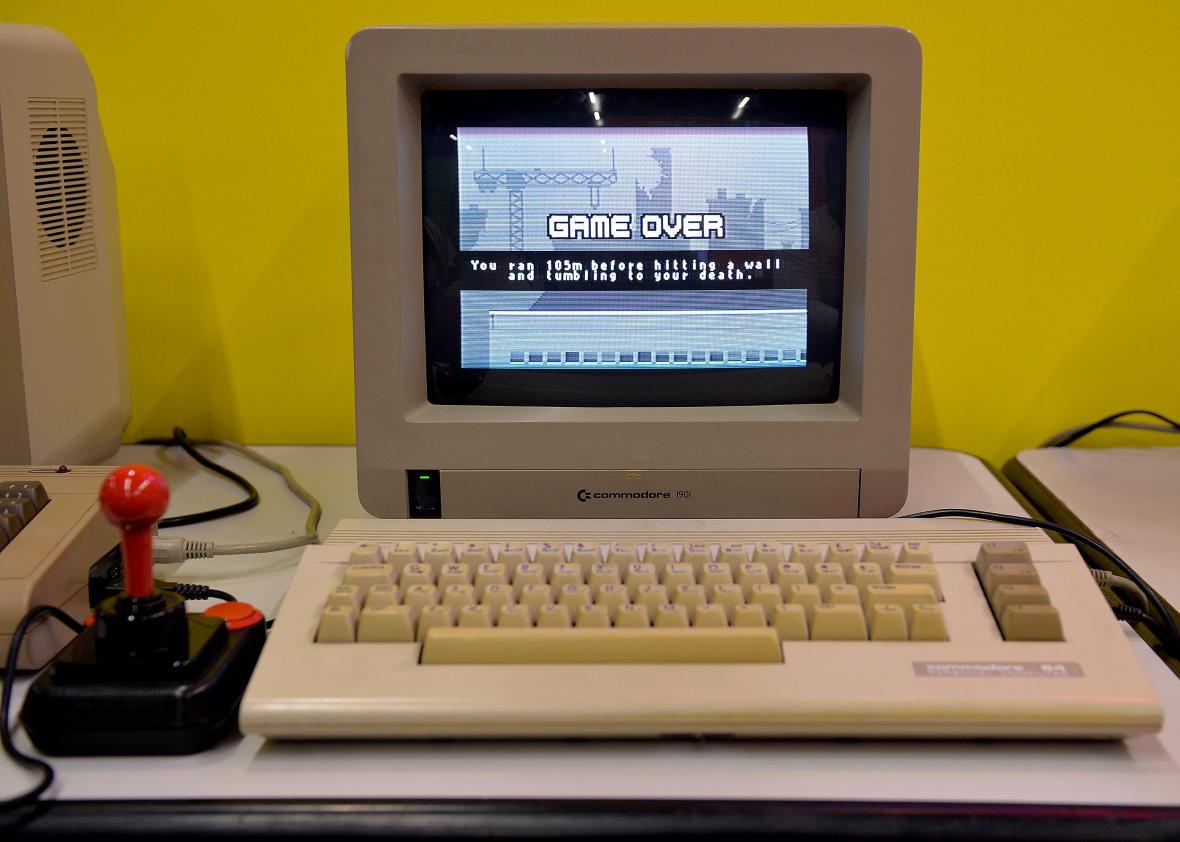

But the internet hates authority. It hates targeted ads and paywalls and data mining because they are difficult to avoid and erected from on high, without democratic consultation or assent. We want what we seek online to be easily accessible and transparent, and we don’t want to have to put in too much work. The Internet is supposed to be the land where it’s OK to give in to temptation, where our desires are fulfilled: a frictionless, wall-free haven from responsibility. We roam, discover, and acquire what we want nearly by willing it to be so. We want to lowercase the internet; doing so gratifies instantly. But like a Saturday spent staring at a screen, the change doesn’t represent our best selves. Deep down we know it’s wrong.