I grew up in Moscow, speaking a surprising amount of Yiddish for a secular kid born in 1959. I could haggle with my grandmother about whether the weather required that a hat be worn, and I knew the meaning of the colorful insults my grandparents lovingly flung at each other.

Alas, somebody forgot to tell me that I was Jewish.

As far as I knew, my grandparents spoke a dialekt, and they came from a mestechko, the Russian word for shtetl.

In the streets, when I heard the insulting-sounding, albeit perfectly reasonable, Russian word yevrey and the derogatory word zhid, I had no idea that these words had anything to do with me, even when hurled in my direction and the direction of my parents. While Yiddish was spoken in our apartment, the word yevrey was often whispered.

A black friend tells me that he became aware of the color of his skin when he was in first grade and that this was typical even in the racially charged Detroit of the ’60s.

In my case, awareness set in in 1967, in mid-June, near the conclusion of the conflict that would become known as the Six-Day War. A young thug whom I considered a friend called me a yevrey and accused me of capturing a canal I’d never heard of. I denied being a yevrey; he escalated the insult to zhid. Since neither word sounded like something I wanted to be, I threw the first punch.

I returned home bruised and bleeding. My parents, who were listening to the Voice of America dispatches from the Middle East, broke away only long enough to confirm to me that I was a Jew, and that it’s fair to call me a yevrey, but it’s not tolerable to call me a zhid.

As I came to terms with my ethnic identity, I found myself in nasty fistfights, some in the streets, some in classrooms and some in locker rooms. Under the law of Moscow streets, if someone calls you a name, you punch the bastard in the mug.

The cost of these adventures was significant and benefits scant. I cannot recall a single fight in which the other guy ended up looking worse than I, especially when I was outnumbered. But in matters of honor, consequences are irrelevant.

After coming to the U.S. in 1973. I was in a position to compare brands of anti-Semitism: American and Soviet. I ended up getting a scholarship at a Washington-area private school.

I don’t want to sound snooty, but I thought American epithets for my people were a bore. Kike—a word of American coinage—was mostly out of circulation. To find it, my friends at St. Stephen’s would have needed to perform some fancy philology, a term many of them would have believed to connote an interesting sexual practice.

Kike emerged in the U.S. about a century ago. Some say the word stems from the ending “ki” in the names of Jews from Slavic countries. Others say it comes from the Yiddish word kaikel, literally “circle.” Immigrating Jews were the type of illiterates who signed their names with circles instead of X’s, regarding the latter as symbols of Christianity.

The epithets yid and hebe had similarly retired by the 1970s, and Hymie, the word once famously used by Jesse Jackson, was too boutique for the white boys at my school. There were robust epithets for other groups—blacks, Poles, Italians, and gay people—but the anti-Semitism I encountered was epithet-free.

I wasn’t welcomed. When I ran for class secretary in 1976, someone painted a swastika on my election poster. The young gentleman thought he did this anonymously, but I know who did it and why. I was engaged in the classic immigrant practice of scraping my way to the top. For some, it’s a disturbing thing to watch.

Of course, I can spot anti-Semites in the same fraction of a second it takes my black friends to identify racists, but I learned to be pragmatic, strategic, calm.

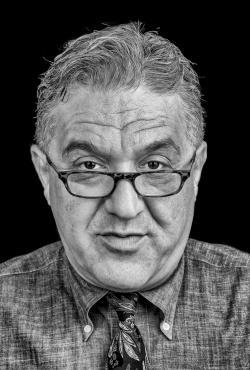

Photo by Gilles Frydman

My novel The Yid is something of an archeological dig for the virulent anti-Semitism of the Moscow streets of my childhood. In fact, it reaches deeper, to late February of 1953, the time when an increasingly demented Stalin was plotting the execution of physicians swept up into the apocryphal Doctors’ Plot, and freight trains were reportedly converging on major cities to carry out the deportation of Jews who survived Hitler’s holocaust.

Much as I admire the strategic thinking the gay community displayed by embracing its epithets, I can’t say that I immediately recognized my novel as an opportunity to reclaim yid. Instead, I was taking ownership of something larger and more ominous: the hateful mythology of an international Jewish conspiracy. I want to imagine how such a conspiracy would form and function. I gave my fictional confederates a noble assignment: assassinate Stalin.

My characters are the opposite of pious. They spell God with a lowercase “g.” They have exhausted their capacity to bow to potentates.

Naturally, the word yid figured in the manuscript. Whenever I attempted to give a short description of the book, I started with: “Moscow, 1953. Three goons come to arrest an old yid …” It sounded like the opening of a vintage comedy act: Borscht Belt, but a few shades darker. Of course, the word yid would have to be used if this story were told in Yiddish.

“That’s your title,” said a friend, a fellow dark humorist, after I described the book to her.

“What’s my title?”

“The Yid.”

The working title at the time was actually Levinson’s Sword. To change it to The Yid—at first I thought the idea was insane. Within seconds, I realized it was brilliant.

In a manner that mimicked my own experience, the epithet did not remain contained. Too big to hide, the Yid scraped his way to the title page. It was what my novel wanted. Who was I to stand in the way?

My father, who lives in Florida, doesn’t love the title, and fears that some readers will take my reclaiming of anti-Semitic lore as a capitulation. If Russian nationalists give out prizes for literature, I would be a contender, he says. Also in Florida, my future mother-in-law, who otherwise seems to like me, refrains from showing the book to her friends.

Recently, a humorless Metro rider in Montgomery County, Maryland, gave a friend of mine a lecture after spotting him reading the bound galleys of The Yid. And my editor tells me that several stores have refused to stock the book out of fear of driving away Jewish customers.

I have no place to hide, nor do I wish to. The title is not A yid, a Jew in Yiddish—it’s The Yid, an anti-Semitic epithet in English. To make sure that no one misses the point, I was going for the closest equivalent to Russian epithet zhid, which I believe would make a nice title for the Russian translation.

If anyone wishes to accuse me of anti-Semitism, I say “mazel tov.”