“Very often,” mourned the French philosopher Antonin Sertillanges, “gleams of light come in a few minutes’ sleeplessness, in a second perhaps. … There is every chance that on the morrow there will be no slightest trace left of any happening.” Unless you own a smartphone. Sertillanges, in 1934, recommended “fixing” mental glimmers in a journal, like butterflies to a board.* In 2015, he might have approached his problem—the problem of time passing, and our forgetfulness—with the Notes app.

If jottings are to interior life what photographs are to life lived out in the world, Notes is Snapchat for your soul. Apple has tricked out iOS9 with a shiny new version of the skeuomorphic iPhone feature with its charming lined-paper-and-yellow-binding design. You can now format text with bold and italics, create checklists, even trace letters with your finger or a stylus. Though the iPeople insist Notes is for “memo-taking,” that is not, in my experience, where its real utility lies. (Maybe if you defined “memo-taking” super-broadly, as in “transcribing a band recommendation and four digits of a telephone number while drunk.”) Not everyone walks around with a Moleskine notebook, but almost everyone has a smartphone. The Notes app therefore serves as a diary for nondiarists, a catchall for the flotsam and ephemera you didn’t even realize you wanted to record.

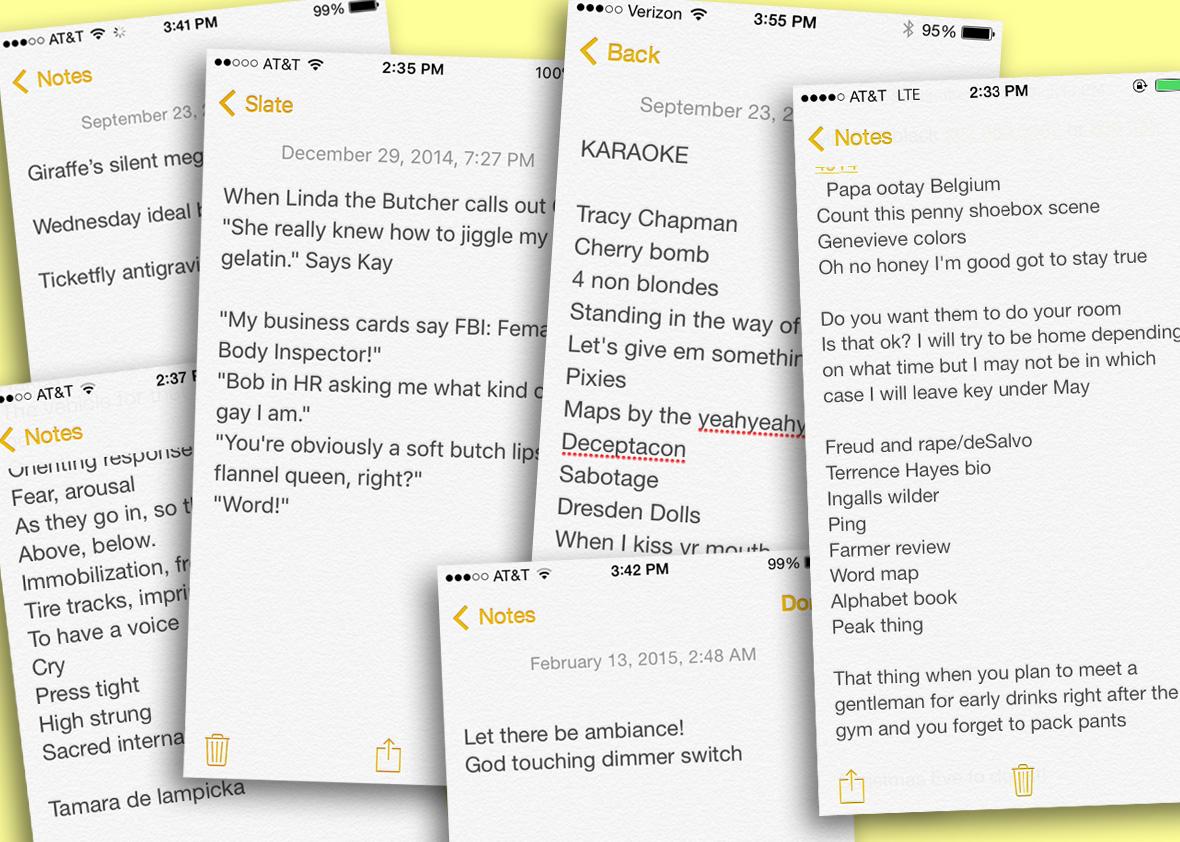

That’s not to say Notes isn’t practical. When I polled friends and colleagues on how they used the app, many spoke of “to-do lists,” “grocery lists,” and “random reminders.” “I can’t really read my handwriting most of the time, so this is a step up!” enthused Slate’s Joshua Keating. Features editor Jessica Winter said she logs “grocery lists, addresses of where I am going, to-do lists, dates I get my period.”

The app can also house broader goals for happiness or self-betterment. Co-workers reported that they keep tallies of books to read, movies to see, songs to download, restaurants to try. (For my part, I Noted an embarrassingly self-helpy “anti-boredom docket” in February, including such sage suggestions as “listen to a podcast,” “text [friend],” “text [different friend],” and “finish The Wire.”) How’s that working out for us? Writer L.V. Anderson confessed she’s seen only two of the 22 films on the aspirational list she made nine months ago. But when we do follow through, Notes can play the role of the traditional journal, reminding us of how we’ve spent our time. “I have a really terrible memory for what books I’ve read/movies I’ve seen,” Keating told me. “So this year I started keeping a running list of them on Notes.”

Speaking of patchy memories, Slate intern Claire Landsbaum has observed a trend of “people [using] the Notes app on their phone to keep track of who they’ve slept with.” The top names get adorned with smiley faces or bonfires.

Other lists reflect more individual interests. Culture editor Dan Kois keeps a ballot of songs that seem karaoke-optimal. Anderson types in “random story ideas I usually then forget about.” Editor Chad Lorenz jots down promising song combinations as the underpinnings of future playlists. Podcaster Mike Pesca plants the seeds of episodes to come in his infamous Gist List, a “long, detailed, occasionally baffling iPhone note” crammed with snippets like “mom jeans” and “Giraffe’s silent megafauna.”

But it’s the less structured Notes that really come alive with wackiness and poignancy. Fragments, loose thoughts, transcriptions of intoxicated consciousness: Such entries turn the app into an accidental mirror for the weirdness of life. Take the writer Rachael Maddux’s impressionistic account of a dinner in Reykjavik, Iceland:

Going through my Notes history, I came across darker stuff too, such as anxious planning for conversations I dreaded for one reason or another. These snippets of micromanaged tone were like Proust’s madeleine: As I read, I suddenly saw myself in transit, worried about an upcoming confrontation, drafting kind-but-firm lines on my phone as the train swayed from side to side. (Did I end up saying them? I can’t remember.) Other entries remain utterly mysterious. “Wednesday ideal bof is 4830”? “Ticketfly antigravity dust”? Jessica Winter also discovered inscrutable scraps of text in her archive: “Max Ernst’s bird Lop Lop, tried to bring her to life through grottagr and frotragr,” read one scribble, perfect for the New Yorker’s poetry section.

Still more digging yielded what I can only assume was preparation for long-ago blog posts. One Note: “Smiles work a preerbal enchantment and Like all magic they come at a cost.” (Preerbal enchantment? Tell me more.) Another: “Blue-veined trouser serpent camel mantrap.” (I think/hope this was for a piece on dirty slang.) Perhaps the most confusing Note consisted of what appeared to be an aborted brainstorm:

Top reasons the US women’s beach volleyball team is sticking to bikinis, even though new regs allow for shorts and sleeved t-shirts.

1. sand

But Notes aren’t only a repository for material you can feel embarrassed about later. I delighted in an Einstein quote—“Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted”—just as my self from eight months ago had hoped I would. I unearthed what might have been a writing guideline, which apparently originated in a Czeslaw Milosz poem: “Human reason … saves austere and transparent phrases.” (Reason is likely not the governing deity of the Notes app, and the phrases conserved are generally neither austere nor transparent. But, to cite another fragment I dredged up, they are part of “the music of what happens.”) I stumbled over the first, uncouth articulation of a question that haunts me still: “Rubio Walker Cruz social Darwinists who dont believe in Darwin wtf.”

The inevitable typos and misspellings might be the best part of Notes. These speak to the spontaneity of each entry, the urgency of getting something down even if it makes no sense to anyone but you. While journals and diaries at least entertain the notion of an audience, Notes are incomplete little prods submitted onto a device that replaces the flimsy lock of a childhood diary with a four-digit passcode. They can completely flummox any reader who’s not already aware of the thought processes behind them (including you, four months later). But anyway, they’re yours. And when you suddenly remember what you meant by “bluegrass man island 426,” they become power outlets into which you’ve finally inserted the right electrical charger; a whole region of your brain bursts into incandescence. The first item on my brand new Notes to-do list? Take more Notes.

*Correction, Sept. 23, 2015: This post originally misstated that a quote from Antonin Sertillanges came from 1998. The quote came from 1934.