Congratulations to Yi-Fen Chou, whose poem “The Bees, the Flowers, Jesus, Ancient Tigers, Poseidon, Adam and Eve” was selected for inclusion in the Best American Poetry anthology for 2015. BAP, launched in 1988 by the writer and professor David Lehman, is co-edited every year by a visiting literary starlord. This year, that starlord was the great Sherman Alexie; previous years have entrusted the scepter to Mark Strand, Rita Dove, and Terrance Hayes.

There’s just one problem: Yi-Fen Chou’s real name isn’t Yi-Fen Chou. It’s Michael Derrick Hudson. Hudson, who works for the Genealogy Center at the Allen County Public Library in Indiana (and from whom we might expect a fuller understanding of the difference between Anglo-European and Chinese lineage), explained his nom de plume in a contributor’s note:

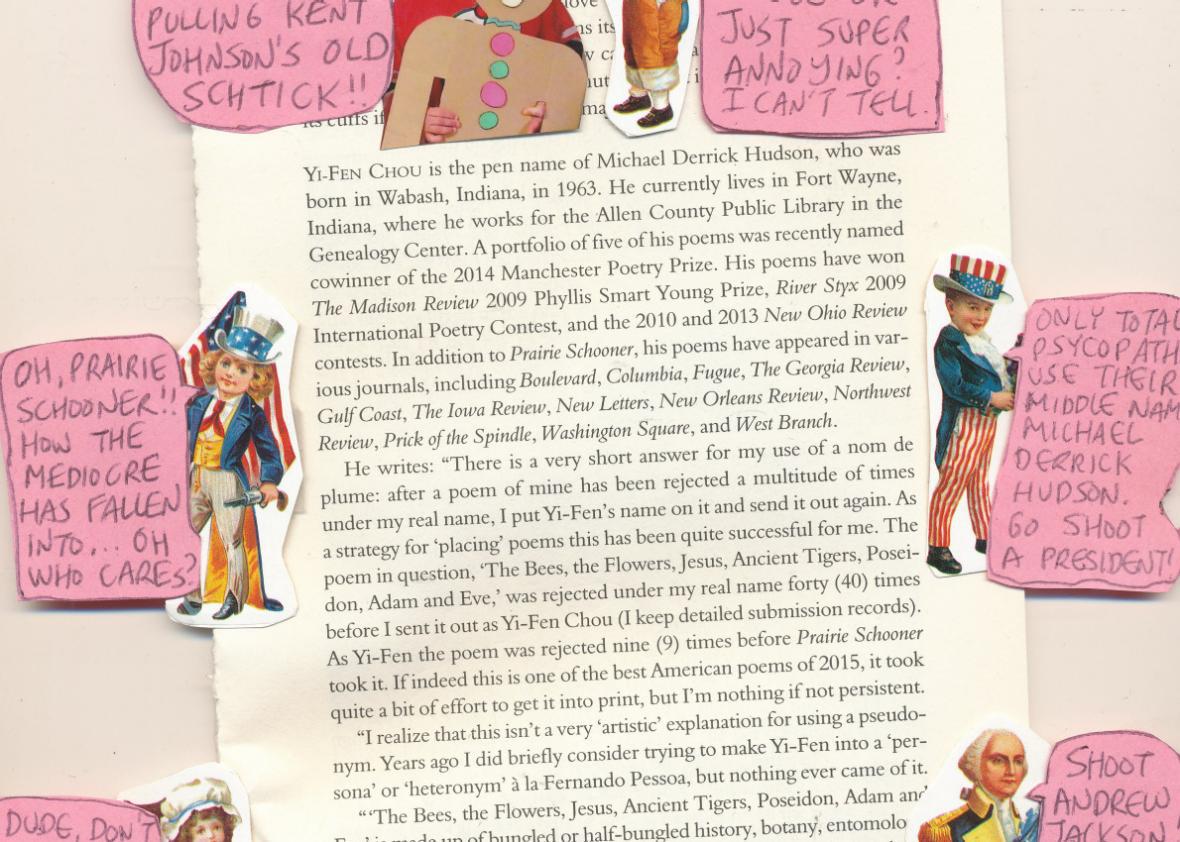

After a poem of mine has been rejected a multitude of times under my real name, I put Yi-Fen’s name on it and send it out again. As a strategy for ‘placing’ poems this has been quite successful for me. The poem in question … was rejected under my real name forty (40) times before I sent it out as Yi-Fen Chou (I keep detailed submission records). As Yi-Fen the poem was rejected nine (9) times before Prairie Schooner took it. If indeed this is one of the best American poems of 2015, it took quite a bit of effort to get it into print, but I’m nothing if not persistent.

That “nothing if not” formulation, which Hudson probably intends wryly, is a risky one, especially given the sensitivities at play. (You are nothing if not an appropriative cheater! one imagines the real Yi-Fen roaring, from some alternate dimension.) On social media, the response was swift and ruthless, spanning at least three (3) platforms.

A Tumblr page festooned with mocking pink thought bubbles—“only total psychopaths use their middle name Michael Derrick Hudson. Go shoot a president!” “Is this racist or white privilege or just super-annoying? I can’t tell”—made the rounds. On Facebook, Timothy Yu, an English professor at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, came forward with a tongue-in-cheek confession. “Like every poet, from time to time I write poems of which I am somewhat embarrassed. Once these poems have been rejected a multitude of times, I send them out again under the name of Michael Derrick Hudson of Fort Wayne, Indiana,” he admitted.

Yu’s sarcastic kicker—that his alter ego must on some level resent “that he is nothing more than a figment of a Chinese American imagination”—gets at the way Hudson’s impersonation of an Asian poet exploits and subsumes Asianness. Hudson has transformed a heritage into a useful stroke of invention that, attached to a poem, might increase his acceptance rate. “I felt that appropriating his name amounted to a kind of poetic justice,” Yu told me.

Hudson’s attempt to game the poetry submissions system is, of course, unethical. He lied to reap the benefits of affirmative action, a set of practices designed to ease the effects of ingrained injustice. BAP stunts aside, it’s still much more difficult for female writers and writers of color to get published than for white men. And, as with the case of Rachel Dolezal, assuming a minority identity when it suits you and then retreating into inherited advantages when it doesn’t pretty much defines white privilege. (Sherman Alexie has published a blog post explaining his decision not to pull Hudson’s poem. It is passionate and charming and asserts that dumping “The Bees” would “cast doubt on every poem I have chosen for BAP.” To me this doesn’t quite follow. I’ve reached out to Alexie and to David Lehman for further comment, as well as to Hudson, and will update this post if I hear back.)

On the other hand, has Hudson’s immoral gambit exposed a flaw in the literary ecosystem? Why should a poem be rejected under one name and accepted under another?

The question seems legitimate but lacks context. The world is awash in great poems. Any selection of the best ones will necessarily rely on extra-literary factors. Most people would rather see diversity be one of those factors than say, marketing or connections. In his introduction to BAP 2015, Lehman writes that “the spirit of democracy on display” in the book is “not inconsistent with the search for literary excellence.” I would go farther: There’s something equalizing about literary excellence—above a certain tree line of creative achievement, poems inhabit the same glorified atmosphere. Who would win between Robert Hayden and Adrienne Rich? Jorie Graham and Charles Simic? It’s an absurd question. (Yes, art at even the highest levels has some striations, but those distinctions—between Frederick Seidel and Shakespeare, for instance—are rarely applicable to a “year’s best” roundup.) And so the criteria that editors apply to separate one tangle of beautiful poems from another will obviously have less to do with the beautiful poems themselves than with the kind of artistic community we want to nurture—one in which people of all backgrounds can speak their particular and irreplaceable truths.

But tell that to the disillusioned speaker of “The Bees, the Flowers, Jesus, Ancient Tigers, Poseidon, Adam and Eve.” (Even the title suggests a numbness to the world’s variety and abundance.) He is a bitter, cynical fellow, prone to lines like:

My life’s spent

running an inept tour for my own sad swindle of a vacation

until every goddamned thing’s reduced to botched captions

and dabs of misinformation in fractured,

not-quite-right English.

Elsewhere, “Chou” laments that he “never amounted to much.” “At my feet,” he writes, “the leaves/ skittering across the driveway say: Thanatos! Thanatos!/ as if to shush me with the bug-holed currency// from life’s latest bankruptcy.”

This is a poetry of grievance, and if flecks of self-mocking humor soften its despair, I’d argue that it’s still slightly more interesting coming from a Chinese American writer than a white one. Perhaps that’s a controversial claim. Yet Yu, the UW–Madison professor, agreed. “There’s nothing explicitly Orientalist in [Hudson’s] work,” he told me. “The tone—grating, flippant, irritated—caught my ear because it defied my expectations” for a young Asian man in Indiana.

“We have this fantasy that authorship doesn’t matter,” Yu continued. “But if that were true, none of this would be happening.”

Perhaps what Hudson’s feat demonstrates is that, without some kind of extradiegetic edge, his poems don’t quite cut it. Is that really the statement he wants to make?