Words may have lost all meaning to the Supreme Court, as Antonin Scalia suggested Thursday in his dissent from the King v. Burwell decision to uphold health care subsidies, but there’s one word that has a meaning quite particular to the Supreme Court: respectfully. It is a long-standing tradition that Supreme Court dissents often conclude with the gracious words “I respectfully dissent.” So it was taken as a grave sign of incomity in 2000 when Ruth Bader Ginsburg concluded her stinging minority opinion in Bush v. Gore with a bare “I dissent,” the Supreme Court’s equivalent of a glove slap to the face. On Thursday, Scalia likewise eliminated respect from his King v. Burwell dissent, concluding his torrent of outrage with “I dissent.” (Even though Scalia thinks that today’s marriage equality decision was a descent into “the mystical aphorisms of the fortune cookie,” that was not enough to provoke an “I dissent” from him, signaling that same-sex marriage might not upset him quite so much as health care subsidies.)

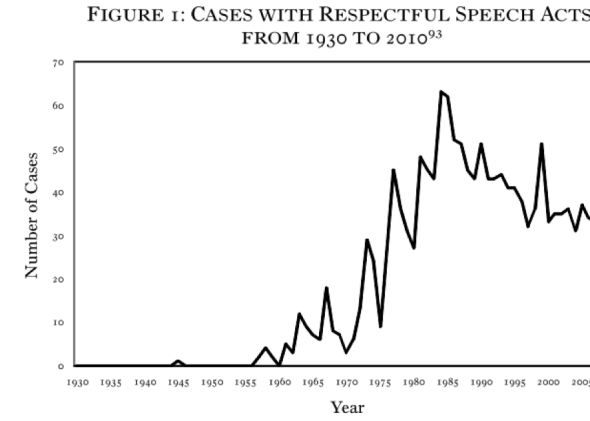

I wondered how often such disrespectful dissent occurred in the hallowed halls of the Supreme Court. Law professor Stephanie Tai helpfully pointed me to a Harvard Law Review note, “From Consensus to Collegiality: The Origins of the ‘Respectful’ Dissent,” that charts the history of dissents both respectful and less so. The convention is one that’s only been around for 50 years, but in that time it has become a quite durable one, making departures from it quite striking.

The note, by New York attorney Chris Kulawik, takes its inspiration from ordinary language philosopher J.L. Austin’s theory of speech acts. In How to Do Things With Words, Austin discussed certain speech acts as “performative utterances,” statements that draw their meaning not just from the semantics of their words but from the social context in which the words are uttered. The classic example is “I do,” in a marriage ceremony, which has a network of implications and commitments far beyond what the two words would mean in any other context. Another example would be when Scalia referred to Ginsburg as “Goldberg” the other week, a seeming slip of the tongue to which some imputed more sinister significance. Likewise with “I respectfully dissent” and “I dissent,” which in the patois of the Supreme Court take on the implications of a courteous response and a furious retort, respectively.

In the early history of the court, dissents were polite, defensive, and even apologetic, stressing the focus on consensus. “In any instance where I am so unfortunate as to differ with this Court,” Justice Bushrod Washington pleaded in U.S. v. Fisher (1805), “I cannot fail to doubt the correctness of my own opinion. But if I cannot feel convinced of the error, I owe it, in some measure, to myself, and to those who may be injured by the expense and delay to which they have been exposed, to show, at least, that the opinion was not hastily or inconsiderately given.” By the 20th century, dissent had become enough of a norm not to require such hand-wringing, though it was still comparatively rare. But by 1950, dissent was both common and far more prominent: Dissents were not just expressions of disagreement but judicial statements. With the Warren Court taking on ever more divisive social issues, the court tried to mitigate its own divisions by embracing a “norm of collegiality,” embodied by the respectful dissent.

Chris Kulawik

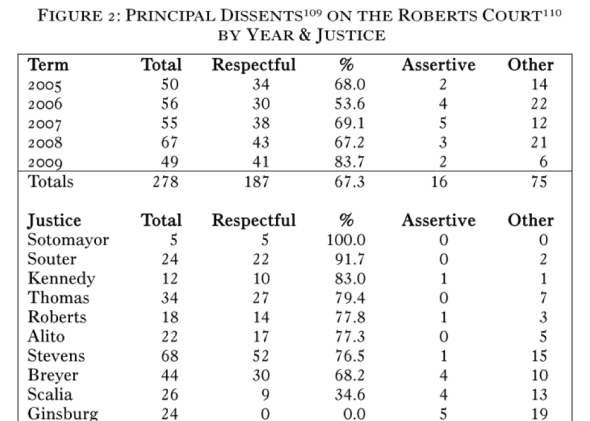

The “respectful” dissent as we know it today emerged on the Warren Court in 1957, especially in the opinions of Charles Whittaker, followed closely by other justices. As with its immediate predecessors, “The respectful dissent is the dominant speech act of the Roberts Court,” being used in 70 percent of dissents. The remainder either have no dissenting speech act whatsoever, or, more rarely, contain what Kulawik terms “assertive dissents,” which “withhold respect where convention requires it.” Of the years 2005–09 that the note covers, most justices hewed to the respect norm, topped by the studiously polite David Souter and the newest appointee Sonia Sotomayor.

Chris Kulawik

We recall that Ruth Bader Ginsburg performed a notorious nonrespectful dissent in Bush v. Gore. Yet a closer look reveals this to be typical behavior of the atypical Ginsburg: She never respectfully dissents. She believes the respectful dissent to be disingenuous when “you’ve shown no respect at all.” Ginsburg also disputes the intrinsic significance of her assertive dissent in Bush v. Gore. She would rather, it seems, be analyzed on substance than performance; she consciously omitted “I dissent” from her otherwise excoriating Hobby Lobby dissent.

Ginsburg’s bluntness separates her from the other judges, whose performative dissents require more interpretive argle-bargle. Most justices reserve the assertive dissent for the most controversial and consequential of cases. John Paul Stevens, usually quite respectful, used “I emphatically dissent” in his Citizens United dissent, his sole assertive dissent. In the 2007 Parents Involved in Community Schools desegregation case, Breyer concluded, “I must dissent.” As Kulawik writes, “an assertive dissent is ultimately an act of protest, a signal from one Justice to the world at large that the majority opinion does not deserve legitimation — that the majority has acted impermissibly and produced significant costs for political society.” Under this interpretation, it is Scalia who protests the most. He ties Breyer for assertive dissents, used in his Defense of Marriage Act (U.S. v. Windsor) and Guantánamo (Boumediene v. Bush) dissents, but he is vastly stingier with his respectful dissents, marking him as the most substantively disrespectful of the justices if we disqualify Ginsburg, who thinks the whole business meaningless. (Perhaps this helps explain why Scalia and Ginsburg have somehow managed to remain friends despite agreeing more frequently over Italian opera than they ever do in English.)

Like the philosophies of W.V.O. Quine, Wilfrid Sellars, and the later Wittgenstein, Austin’s philosophy was a rejoinder to the logical positivist idea of meaning, which posited that meanings of statements could be specified atomically and precisely. Perhaps surprisingly, Scalia’s textualist philosophy invokes this holistic and sometimes squishy perspective: “Words, like syllables, acquire meaning not in isolation but within their context,” he wrote in K Mart v. Cartier (1988), uncannily echoing Jacques Derrida’s deconstructionist maxim, “Il n’y a pas de hors-texte” (“there is nothing outside context”). “Context always matters,” Scalia repeated in his King v. Burwell dissent. Such linguistic indeterminacy may be correct (I happen to think it is), but it makes Scalia’s supposedly precise textualist philosophy no less vague than the philosophy of an evolving “living Constitution” to which Ginsburg subscribes. Perhaps this is what Scalia meant when he said of Ginsburg, “She’s a really good textualist.” In that context, textualism, I respectfully submit, is just another act of interpretive jiggery-pokery.