What do you call the situation in Baltimore this week? Riots? Protests? An uprising? As the city responds to the death of Freddie Gray, and the police respond to the city, the hashtag #BaltimoreUprising is ascendant among those with a left-leaning point of view. For these participants and onlookers, it is starting to replace #BaltimoreRiots as the verbal symbol of the past few days’ unrest. On Twitter, the #BaltimoreRiots feed contains a lot of “rule of law”–themed tweets:

Whereas you’re more likely to find commenters who are sympathetic to the protesters in #BaltimoreUprising:

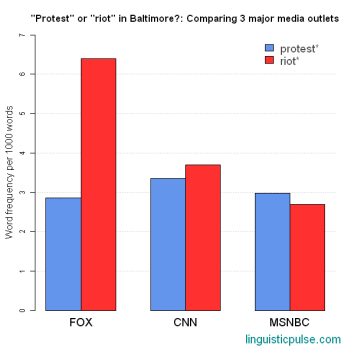

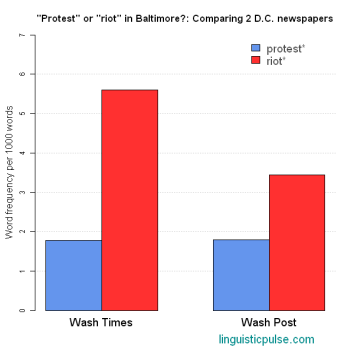

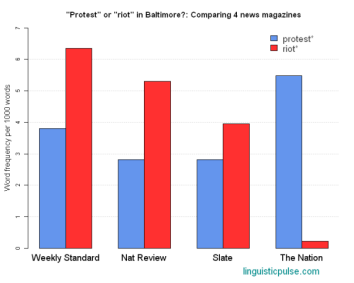

It’s not just Twitter. On Linguistic Pulse, Nic Subtirelu compared the use of the terms riots (plus rioters, rioting, etc.) and protests (plus protesters, protesting, etc.) across a variety of news platforms. Here’s what he found:

via Nic Subtirelu

via Nic Subtirelu

via Nic Subtirelu

As Subtirelu points out, venues that present themselves as conservative are more likely to opt for riots over protests, thereby “eras[ing] the political messages and purposes of people in Baltimore.” More “moderate and progressive venues” are likelier to reach for the terms that “imbue many of the people in the streets with political purpose.” (As seen in the chart above, Slate has used both terms.)

Here’s exhibit C. On Monday night’s live coverage of the fracas, CNN commentator Marc Lamont Hill laid bare the reasoning behind such linguistic sleights-of-hand. “I’m not calling these people rioters,” he told Van Jones and Don Lemon. “I’m calling these uprisings and I think it’s an important distinction to make. …There have been uprisings in major cities and smaller cities around this country for the last year because of the violence against black female and male bodies forever and I think that’s what’s important.”

What exactly is at stake in the semantic tug-of-war between riots and protests, riots and uprisings? As both Subtirelu and Hill suggest, the second two options demand that we take the people involved more seriously, as agents with purpose and grievance. The verb protest especially carries intimations of virtue; in the mid-15th century, it meant “to declare formally or solemnly,” as in “to protest one’s innocence.” Today the word implies principled disapproval and moral fiber: The stalwart protester stands in the rain, picketing for equal pay. Indeed, one protests against something, not just for the hell of it. The act requires fortitude but—perhaps thanks to Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr.—it is an effort of will and ethical imagination, not arm and hammer. Protest’s connotations of self-discipline seem to counter the threat of wanton violence.

An uprising sounds, at least to my ear, slightly unrulier than a protest. Yet #BaltimoreUprising has the appeal of uniting what could be seen as disparate acts of chaos and provocation (riots) into a single movement. It adds legitimacy and shape to the events on the ground, even as its echoes of resurrection imply a renewal after (grave) injustice. An uprising evokes inequalities, oppression inflicted and then resisted. It confers on participants a sheen of romance or heroism, especially in light of history’s many idealistic rebels, from Shay to John Brown to the Haitian insurrectionists to the founding fathers themselves.

And then there’s riot. From the 12th-century French word for a “dispute, quarrel, tedious talk, chattering,” also a euphemism for sex. In medieval England, hounds that “ran riot” went in error, zigzagging helter-skelter after the wrong scent. “Riot grrrls” were punk iconoclasts. Conjuring up destruction without cause, the word often appears in proximity to senseless. As with thug versus protester, or senseless versus purposeful or directed, the emphasis in riot falls on lawlessness, chaos, disorder—not the long, moral arc of human affairs.

The motivations for deploying each of these terms aren’t hard to parse. Those who wish to express solidarity with people outraged by a police force that kills with impunity want to use language that rationalizes, even glamorizes, the widespread anger. Those horrified by the arson and the looting want to convey their consternation, to emphasize that scaring homeowners and brutalizing community businesses won’t help anyone. It is a delicate line to walk. We need a way to credit the intense frustration Freddie Gray’s neighborhood must feel in the wake of his death, without condoning the destruction of innocent people’s property. If a riot feels too pejorative, a protest feels too anodyne, an uprising overly noble and centralized. So what do we say?

Rabble-rousing? It captures the haphazard nature of the situation but seems dismissive, patronizing. Rally? Too Bring It On. Demonstration? That’s an awfully bloodless term for waves of violence that left windows shattered and a CVS in flames. Perhaps the problem is not so much that no English-language word occupies a happy middle between thoughtful civic gesture and nihilistic smashing. It’s that we demand a word that encompasses contradictions: behavior that is senseless and yet makes sense, that is at once unacceptable and understandable.