If a tree falls in the forest in a comic book, but no one is around to write

Comics are a visual medium, but sound is an essential element of the “imaginary space” their creators are building, at least according to Lee Marrs, author of the Pudge, Girl Blimp series and a “founding mommy” of Wimmen’s Comix. A comic with the sound effects removed might be a significantly different reading experience, almost as though a central character had been excised.

Marrs notes that representations of sound in comics are emblematic of the art form, and over time, a canon of onomatopoeia has developed. As with any transcription, these spellings are constrained by a language’s sounds and its writing system(s), so onomatopoeic words for the same sound, a barking dog or creaking floorboard, often differ from language to language. When comics are translated, the sound effects are usually converted as well.

Writing for a wide audience in comics like Wonder Woman and Batman, Marrs tended to use the standardized forms, but comparing her personal comics with the more mainstream collaborations, Marrs says, “You hear things and see things that are going on and decide more organically how to represent them.”

Sometimes it’s an artistic decision to tweak an old sound word or imagine an entirely new one, and sometimes the familiar vocabulary of comics onomatopoeia doesn’t provide an obvious option.

Ryan North, writer of The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl, among other things, considers a script incomplete without sound effects. He explains how he finds the right spelling for novel sounds like the “language” of squirrels:

The secret to this is having a room you can be alone in, trying to make the sounds yourself, and seeing what comes out. It’s similar to if you’re writing a character talking with their mouth full: the only way I know to transcribe that is to stuff my fist in my mouth and write down what sounds I make when I try to talk. For Squirrel Girl I’ve watched a lot of squirrel videos on YouTube and tried to transcribe what noises they make, but I’m not sure I’m there yet. I am trying to up my squirrel noises game. The trick is you want something that reads as “squirrel noise” but that isn’t too long or distracting. I’ve settled on “chit chuk chitty” style noises for now since they read easily, but I could see going to more “chhhhhtkkt” in the future. It hasn’t been standardized yet, you know? We all know Wolverine’s claws go “SNIKT” when they come out, but there isn’t such a long and proud tradition for squirrel chatter. YET.

These representations of sound, standardized or novel, must consider not just the spelling, but visual cues suggestive of sound qualities.

Marrs explains two basic indicators: the louder the sound, the larger the word; and repetition of letters shows duration. These principles can also be applied to some extent to, say, a text message, whereas the medium of comics allows a degree of freedom to graphically imbue a sound word with expression, from a delicate pizzicato to a bone-rattling sonority. The color, shape, and weight of the lettering may hint at timbre or physical characteristics of whatever is making the noise.

But faithful transcription doesn’t always drive the choice of a sound word and its particular representation. Ben Towle, author of the Oyster War Web comic, mentions other considerations. On spelling: “I just make up something that looks [good] and reads well.”

And on choosing the right words:

I try for words that evoke sounds, but I also take into account that those words create a rhythm when read on a page. I try to establish a nice sequence of varying words, typefaces, colors, and sizes whenever I can.

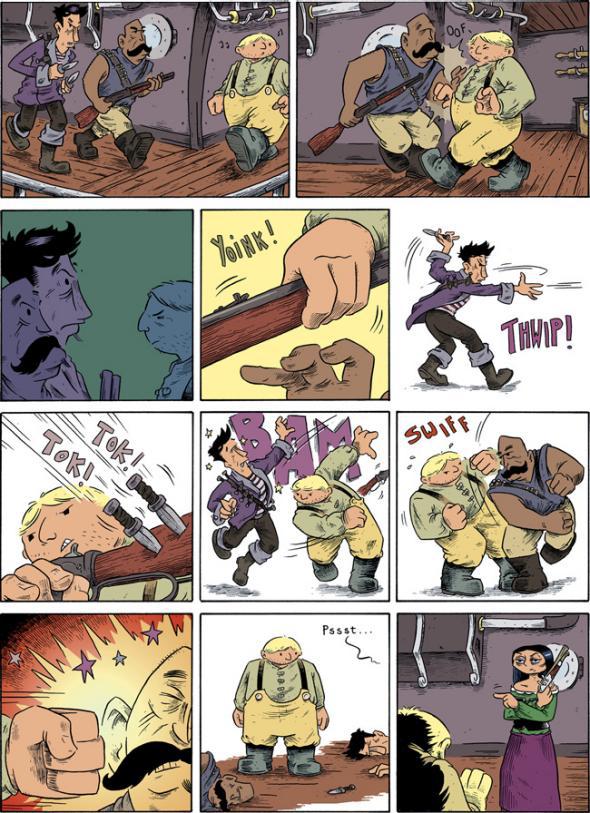

From Oyster War, courtesy of Ben Towle

And on capturing a specific sound in visual form:

Designing your sound effects lettering so that the reader “hears” the sound when reading seems like a logical approach—and I’m sure that’s the intent behind a lot of the most commonly used sounds in comics—but I’m not positive that’s how they actually function. I know I for sure don’t really hear sounds in my head as I read comics. I think they work more just as a “this thing is making a noise” indicator—in the same way that a curvy word balloon indicates, “this is something a character is thinking.” I’m thinking, for example, about sound effects like “SHATTER!” That’s not so much an actual connotation of a particular sound, but rather an indication that something has broken and is making a sound in the process.

As Towle notes, sound effects are loaded with more information than just what a thing sounds like. Among the diversity of form and function, they can often clarify the events in a panel by enhancing an action that is hard to capture in a still image. A sound might suggest degree or severity, for example, of an impact. Other important storytelling information can only be communicated through sound. It might be important, for example, to indicate the origin of a noise by its position in the panel or with a “tail” pointing to the source.

Effects like

Art by Erica Henderson, published by Marvel Comics

Cohn ventures that because standardized sound effects become associated with certain actions, they may make comics easier to understand, especially compared with unfamiliar sound words. This echoes Marrs’ approach to mainstream comics. Savvy readers recognize that

A visit to the friendly neighborhood comic shop, or a cup of coffee with the Sunday funnies will reveal remarkable variety in the representations of sound, a result of singular aesthetics and the many competing objectives. But one motive seems to often trump them all. As Marrs puts it, “You’re looking to make things funny.”

Follow @lexiconvalley on Twitter and on Facebook.