People tell me I sound gay. And I totally do.

Eh? What does “gay” even sound like? Really, when you think about it, how could there possibly be a correlation between who we sleep with and how we talk?

The way someone uses language can tell us a lot about who they are. When you hear a person talk, before you even see them, you can probably guess their age, gender, ethnicity, social class and level of education, and maybe even where they’re from (or at least whether they’re from the same place as you or not).

But what about sounding gay? Unlike speech patterns tied to ethnicity, class, or education, it’s not something I picked up automatically since I didn’t really know any gay people growing up. For me at least—and I’m certainly not going to speak for everyone—I sound gay in the same way that I dress like a dork. That is, research in sociolinguistics and linguistic anthropology has found that the way we use language—especially the small variations in things like pronunciation, word choice, how much we do or don’t interrupt someone, etc.—can be as much a part of how we form our social identities as the clothes we wear or the music we listen to.

One of the first people to look at the relationship between social groups and linguistic styles was Stanford University linguist Penny Eckert, working in a suburban Detroit high school in the early ’80s. She found that a change in the way words were being pronounced—saying words like hot, bus, and bed more like hat, boss, and bud—correlated with other aspects of a person’s style—like how flared their jeans were and how feathered their hair was. In short, despite growing up in the same area and attending the same classes together, the “jocks” and the “burnouts” (remember, this was the early ’80s) talked differently.

Later, looking at the “southern-ness” of the accents of Texan women, Carnegie Mellon researcher Barbara Johnstone showed that language variation doesn’t just correlate with other aspects of style, it also helps to create our style—and that people can strategically deploy their linguistic style just as they might strategically roll up a sleeve to show off a mean tattoo before a fight. Texas English and Southern English have a lot in common—like diphthongization of vowels (“a drawl”), use of y’all, and elaborate linguistic ways of expressing politeness. So Johnstone found that in the case of Texas women, when they wanted to sound like they shared “traditional, rural, small-town” values (even if they were born and raised in urban Dallas), they would play up these features in their own speech—using a “Southern drawl” to make people think you’re a Southern belle, in other words.

Getting back to sounding gay, then … when I think about creating my own identity, I make choices about how to present myself to the world. And these choices—not only in how I dress, or where I hang out, but also in what I talk about and even how I talk—draw upon a social “code” that we all share and that I can use to highlight different facets of my identity and different styles. And one of those styles is “gay man” (actually, I’m aiming for “queer hot dad style,” but success has so far been tenuous).

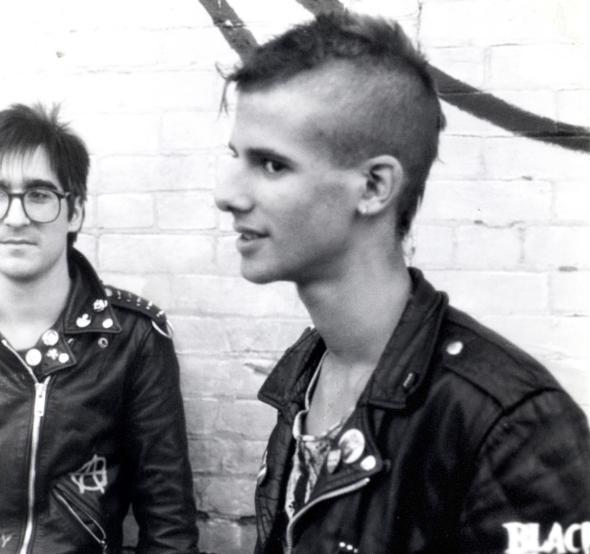

Linguistically, “gay style” has been linked to a lot of different features, including more varied pitch (“sing songy”), longer “S” sounds (or a “lisp”), clearer releases of stop consonants (“precise enunciation”), and even a falsetto voice. But none of these have to be present for someone to sound gay, and any one feature by itself wouldn’t do much. For example, a longer pronunciation of “S” consonants all by itself won’t make you sound gay any more than a Sex Pistols T-shirt all by itself would make you look punk. But in the context of a whole suite of these signifiers, we can hear something like my “precise enunciation” as sounding gay, even if among other signifiers, we might interpret the same thing as “sounding educated,” “sounding picky,” or even “sounding Jewish.”

And this isn’t just true in Dallas and Detroit. Researchers studying language variation have made similar discoveries across all kinds of communities—that linguistic style is as much a part of the social order as anything, and once you know the local code, then hearing someone speak can tell you not just if they’re male or female, but also if they’re cool or dorky, gangster or goody-goody, jocks, stoners, hipsters, freaks, geeks, punks, queers, or any other social category that might be relevant at a given time and place.

So, if you happen to hear me on the radio or catch me on YouTube one day and you’re like, “Oh yeah, dude sounds hella gay. And maybe kinda sexy,” then that’s awesome. That’s exactly the identity I’m trying to construct. That’s just my style.

Follow @lexiconvalley on Twitter or on Facebook.