Like most people, I enjoy burritos. Unlike most people, I also enjoy learning about ancient hieroglyphic writing systems, because I’m Indiana—er—Language Jones. A while back, I bought Andrea Stone & Marc Zender’s Reading Maya Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Maya Painting and Sculpture, and checked out a number of similar books from the library. I skimmed and enjoyed them, and then returned them. Stone & Zender took a place on my bookshelf and I moved on to other things, not anticipating I’d be able to see the Mayan ruins in Mexico any time soon.

Then it happened.

I went to a Chipotle in Philadelphia, looked at the wall, and realized their design was more than just decoration. There, looking back at me, was K’awiil, also known as God K, the “most ubiquitous god in Classic Maya art.”

Next to K’awiil was a glyph representing a lord, possibily Juun Ajaw, one of the Hero Twins. All over the wall was seeing bits and pieces of legible, decipherable Classic era Mayan art. Here, the glyph for mountain. There, a shark.

Then I noticed some weird things. Like what I thought might be K’awiil had a bird on his head (because, why not put a bird on it?). A lord seemed to be writing, but with a burrito instead of a reed stylus. My studies had not prepared me for this.

I couldn’t just tell myself “that’s interesting,” and move on. So I did some research and found that the wood and metal sculptures at many (or maybe all) Chipotle locations were provided by a company named Mayatek Inc. Some of their artwork is surprisingly informed, and the names suggest that the creators are familiar with Maya art. Other works are named strange things that suggest little familiarity with what the art represents. There are some clearly modern embellishments on ancient symbols (like putting a bird on it, but said bird is not a quetzal).

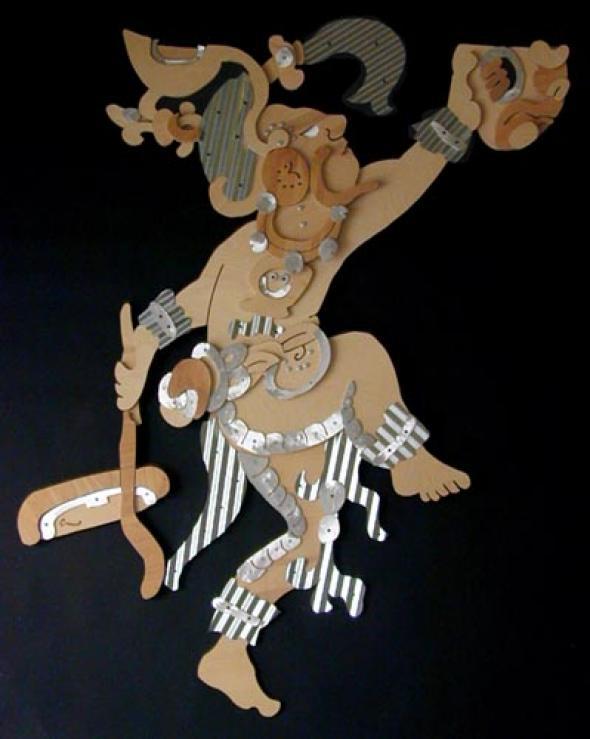

Courtesy of Mayatek Inc.

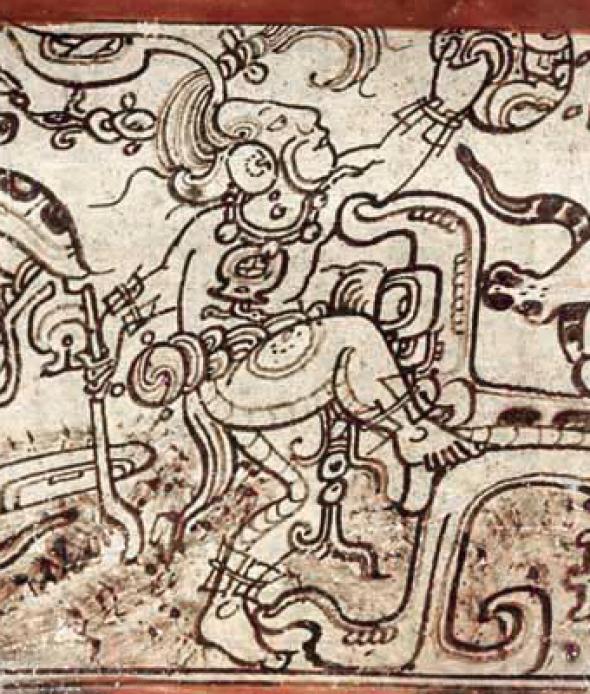

For instance, the above is referred to on the Mayatek website as “dancer.” There is a similar sculpture called “warrior dancer.” However, anyone with even a passing knowledge of Maya art will recognize this is not a dancer, but a specific god. Lucky for you, reader, I have just such a passing knowledge: This is Chahk, the Maya rain deity. In his right hand is the axe he uses to strike clouds to make it rain. In fact, the above sculpture looks suspiciously like Chahk as represented in the Dresden Codex:

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Similarly, the below is referred to as “baldy,” on the Mayatek website. However, the distinctive mark on the cheek is an indicator that the person depicted is a lady (as in “Lord and ____”). While, as it has been pointed out, ladies can be bald, I would argue the unmarked case is not, and “baldy” is not an appropriate appellation for a lady, bald or not—suggesting the iconography was copied without full understanding.

Courtesy of Mayatek Inc.

In the photograph I took at the top, from a Chipotle restaurant in Philadelphia, the second glyph in the first column looks like a shark head, the glyph for stone, and a fish. The bottom glyph in the first row looked to me like a lord, although it seemed likely he’s Juun Ajaw.

Hilariously, the top right glyph in the same photo above looks like Acan, the god of alcohol, who is associated with swarms of bees, since bees are attracted to xtabentún (an alcohol made from fermented honey and tree bark). And by “associated with bees” I mean “he literally vomits swarms of bees.” I’m pretty sure that bit is before he ritually decapitates himself. (“Chipotle: so good, you’ll vomit bees and decapitate yourself!”)

The Dresden Codex

There’s also a sculpture that is clearly Ixchel, the jaguar god, from the Dresden Codex.

Courtesy of Mayatek Inc. and the Dresden Codex, respectively.

Perhaps my favorite find was this:

Courtesy of Mayatek Inc.

… which looks a lot like God A, one of the Maya Death Gods (which, by the way, is an excellent name for a band).

This would not make Chipotle the first major American chain restaurant to decorate with death iconography from another culture (that distinction may go to P.F. Chang’s, with their terracotta soldiers), but I’m of the opinion “death by burrito” should be about portion size, and not about inadvertently invoking the wrath of an ancient deity.

In order to get more information, I wrote an email to Dr. Marc Zender, one of the leading scholars on Maya glyphs and author of The Book on the subject, asking if he could tell me whether the bas relief decoration at this Chipotle was imitating some known work or complete gibberish (email title: “a frivolous question”). To my surprise, he responded, and the answer is that it’s a little of both. He told me that the artist for Chipotle intended to copy a well-known collection of stucco glyphs from Palenque’s Temple 18.

He explained: “The text was commissioned by the early 8th-century king K’inich Ahkal Mo’ Nahb, and had fallen from the rear wall of a temple in antiquity. The stuccos were then recovered piecemeal by several different archaeological projects between the 1920s and 1950s. Primarily because their original order couldn’t be determined, but also because most of them couldn’t be read at that time, the curators at Palenque’s archaeological site museum unfortunately ended up mounting them in (unreversible) cement, placing similar signs next to one another and creating a nonsensical text. “

He went on to explain that “the Chipotle artist has also picked glyphs at random from this collection and has made his best attempt to copy them. It’s not a bad effort in some places, but note the ‘bird with wings’ the artist has created in the bottom rightmost glyph, as well as some missing or invented details in a few other places.” So my intuition’s that (1) it was partially invented and (2) the artist followed the Portlandia mantra “put a bird on it” both check out! I was paying attention.

Then, Dr. Zender made my day. “Just for the fun of it,” He translated the glyph blocks from Chipotle: (left to right, top to bottom):

u-K’AM-ma-K’AJAN?-ch’o-ko

uk’amk’ajan ch’ok

“the youth’s rope-taking” (a ceremony)

u-TZ’AK-AJ

utz’akaj

“its count” (calendric information)

WAX-YAX-SIHOOM-ma

“6 Yax” (part of a date)

chu-lu-ku-?

Chuluk … (pre-accession name of the king)

i-K’A’-yi

i k’a’ayi

“his … stopped” (a death verb, here referring to the king’s father)

TIWOL?-4-ma-ta

Tiwohl Chan Mat (the father of the king)

mu-ka-ja

muhkaj “he was buried” (again referring to the father)

u?-na-ta-la

u naahtal “the first”? (ordinal title?)

MO’-na-bi

… Mo’ Nahb (part of the name of the king)

Dr. Zender also explained that the “shrunken head” glyph I thought might be God A is actually a complex Early Classic spelling of the name of the serpent deity Chak Bay Kaan (CHAK-ba-ya-ka-KAAN). He went on “We’re still not sure what bay means, but the other portions of the name are ‘Red … Serpent’.”

So there you have it folks. Death verbs. “He was buried.” Enigmatic dates. Mysterious serpents. Next time you’re at Chipotle, forget the secret menu and instead focus on what one of my colleagues at UPenn enthusiastically referred to as a “disjoined, incoherent stream of historical tidbits.” (Said colleague continued, “in that sense, it’s not that different from the history of the non-European world that most people get anyway.”)

Now if I could only figure out why a restaurant with a Nahuatl (=Aztec) name has Maya glyphs everywhere …

A version of this post appeared on Language Jones.

Follow @lexiconvalley on Twitter or on Facebook.