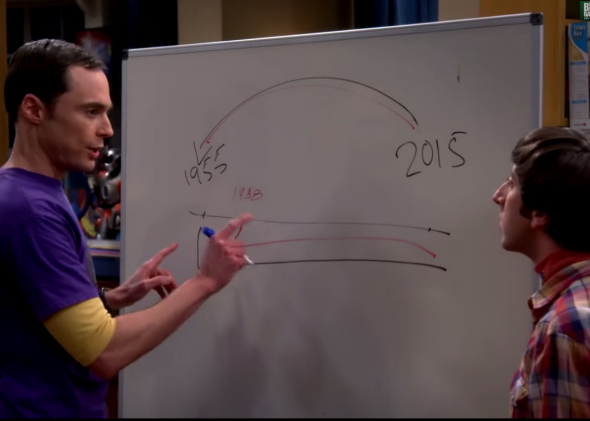

A recent episode of The Big Bang Theory shows Sheldon, Leonard, Raj, and Howard watching Back to the Future, Part II and discussing the appropriate tense to use when talking about something that happened in an alternate past timeline. Here’s the scene, with a transcript via Harrison Tran.

Howard: Wait, hold on. Pause.

[music stops]

Howard: Something doesn’t make sense. Look. In 2015 Biff steals the Sports Almanac and takes the time machine back to 1955 to give it to his younger self. But as soon as he does that he changes the future, so the 2015 he returns to would be a different 2015. Not the 2015 that Marty and Doc were in.

Leonard: This is Hot Tub Time Machine all over again. Look. If future Biff goes back to 2015 right after he gives young Biff the Almanac, he could get back to the 2015 with Marty and Doc in it. Because it wasn’t until his 21st birthday that 1955 Biff placed his first bet.

Sheldon: But whoa, whoa. Is placed right?

Leonard: What do you mean?

Sheldon: Is placed the right tense for something that would’ve happened in the future of a past that was affected by something from the future?

Leonard: [thinks] Had will have placed?

Sheldon: That’s my boy.

Leonard: OK. So, it wasn’t until his 21st birthday that Biff had will have placed his first bet and made his millions. That’s when he alters the timeline.

Sheldon: But he had will haven’t placed it.

Howard: What?

Sheldon: Unlike Hot Tub Time Machine, this couldn’t be more simple. [laugh track] When Biff gets the Almanac in 1955, the alternate future he creates isn’t the one in which Marty and Doc Brown ever used the time machine to travel to 2015. Therefore, in the new timeline, Marty and Doc never brought the time machine.

Leonard: Wait, wait, wait. Is brought right?

Sheldon: [thinks] Marty and Doc never had have had brought?

Leonard: I don’t know, you did it to me.

Sheldon: I’m going with it. Marty and Doc never had have had brought the time machine to 2015. That means 2015 Biff could also not had have had brought the Almanac to 1955 Biff. Therefore, the timeline in which 1955 Biff gets the Almanac is also the timeline in which 1955 Biff never gets the Almanac and not just never gets: never have, never hasn’t, never had have hasn’t.

Raj: He’s right.

So of course all this is just a good excuse to combine two kinds of geekery: sci-fi and grammar: How realistic is this back-to-the-future tense? The main way Sheldon and Leonard twist the verb-tense syntax is to allow auxiliary have to take complements that it doesn’t take in monolinear-time Standard English. First, they put it with the modal will, when modal auxiliaries are always the first in a series of auxiliary verbs, even in outlandish strings such as will have been being eaten. Second, they put it with itself, in had have had brought and had have hasn’t.

Another kind of auxiliary combination we don’t get in monolinear-time Standard English is the past tense (or past participle) auxiliary had after a modal, in could not had have had brought. In our English, modals always take a base form (have), not a past-tense form.

Finally, there’s the combination of the negative contraction haven’t with will in will haven’t placed. In our English, the contraction has to come in the first auxiliary verb: won’t have placed.

But never mind the seeming syntactic violations. In a world with time travel, the language will have to evolve. My question was whether Sheldon and Leonard’s new syntactic rules for these tenses were semantically consistent with each other. In short, they’re not.

The main situation Sheldon and Leonard are discussing is an event time (young Biff placing a bet) that occurs later than a reference time (when young Biff receives the Almanac), but before the time of utterance (2014, in Sheldon and Leonard’s apartment). Ordinarily, this kind of situation would call for the so-called “future in the past“: Biff would place his bet sometime later.

The complication is that the event time and the utterance time are now in separate timelines. Even for this situation, though, ordinary English has an appropriate choice: the perfective version of this future in the past: would have placed. But there’s one more complication: We’re talking about an event that not only did not happen in our own timeline, but also did happen in an alternative timeline. So how do Sheldon and Leonard propose to designate such an event? They use the past-tense form had, followed by a normal future perfect tense (will have had), to get had will have had. Let’s call this the “alternate future in the past” tense. This tense also puts its negative contractions in a different place, as noted earlier: had will haven’t placed.

However, Sheldon and Leonard don’t follow these rules the very next time they discuss an event that occurs later than a reference time but before the time of utterance, in an alternative timeline: Doc and Marty’s trip in the time machine. By the rules created so far, it would be never had will have brought (or if they wanted to use a negative contraction, had will haven’t brought), but instead, they go for the stacking of forms of have instead, leading to Sheldon’s culminating string never have, never hasn’t, never had have hasn’t. These are elliptical forms, which I surmise would all finish with gotten if they were fully spoken.

Still amusing, but it would have been funnier if these tenses had turned out to be consistent with each other, even after my poking at them.

The grammar problem posed by time travel was also explored in 1980, in Douglas Adams’ The Restaurant at the End of the Universe. I was inspired to look up what he wrote, and was hoping to compare his tenses with Sheldon and Leonard’s. The relevant part starts at the beginning of Chapter 15:

One of the major problems encountered in time travel is not that of accidentally becoming your own father or mother. There is no problem involved in becoming your own father or mother that a broad-minded and well-adjusted family can’t cope with. There is no problem about changing the course of history–the course of history does not change because it all fits together like a jigsaw. All the important changes have happened before the things they were supposed to change and it all sorts itself out in the end.

After reading the first paragraph above, I was excited to notice that Adams’ subscribed to the view of time travel in which you cannot alter timelines, unlike the Back to the Future scenario in which you can. Would these differing assumptions be reflected in the hypothetical grammars?

Sadly, no. Although Adams imagines more kinds of twisted temporal situations than Sheldon and Leonard discuss, he never bothers creating new verb tenses. Instead, he chooses to leave them to the readers’ imaginations, while using funny grammar jargon to name them. Continuing from the beginning of Chapter 15:

The major problem is quite simply one of grammar, and the main work to consult in this matter is Dr. Dan Streetmentioner’s Time Traveler’s Handbook of 1001 Tense Formations. It will tell you, for instance, how to describe something that was about to happen to you in the past before you avoided it by time-jumping forward two days in order to avoid it. The event will be described differently according to whether you are talking about it from the standpoint of your own natural time, from a time further in the future, or a time in the further past and is further complicated by the possibility of conducting conversations while you are actually traveling from one time to another with the intention of becoming your own mother or father.

Most readers get as far as the Future Semiconditionally Modified Subinverted Plagal Past Subjunctive Intentional before giving up; and in fact in later editions of the book all the pages beyond this point have been left blank to save on printing costs.

These two examples are the only pieces of pop culture I know of that specifically discuss new verb tenses to handle time travel, although collisions between time travel and talking about time are relatively common in the time-travel genre: Time travel tenses have their own page on TV Tropes.

Fortunately, literary description already has a simple solution, at least for Sheldon and Leonard’s problem: Even without time travel, when you stop reading or watching a story, all of the events in it are taking place, have taken place, and will continue to take place. Have Romeo and Juliet fallen in love yet? That’s a meaningless question: They just do, in Act 1 Scene 5. So it’s a well-established convention that we talk about literary works in the eternal present: As long as we’re outside the events in Back to the Future, we can just say that Biff gets the almanac, he places a bet, he travels back in time. How Biff should talk about it, on the other hand, is something that has will haven’t been figured out yet.

A version of this post appeared on Literal Minded.

Follow @lexiconvalley on Twitter and on Facebook.