Apple has just released an update for iOS 8, the operating system that runs on iPhones and iPads, and they’re supporting 3rd party keyboards for the first time in iOS history. Perhaps that’s partly why I’m a little bit keyboard-obsessed right now: Over the last week, I have typed on 11 different devices: an old iPhone, a new iPhone, an iPad, two laptops, a desktop, a Kindle Fire, a Kindle Paperwhite, a TiVo, a Surface, and an old-school typewriter.

Every device apart from the TiVO’s on-screen keyboard uses a QWERTY keyboard layout by default. But why are we even using the QWERTY keyboard in the first place, and what can trends in computational linguistics tell us about the future of inputting text into machines?

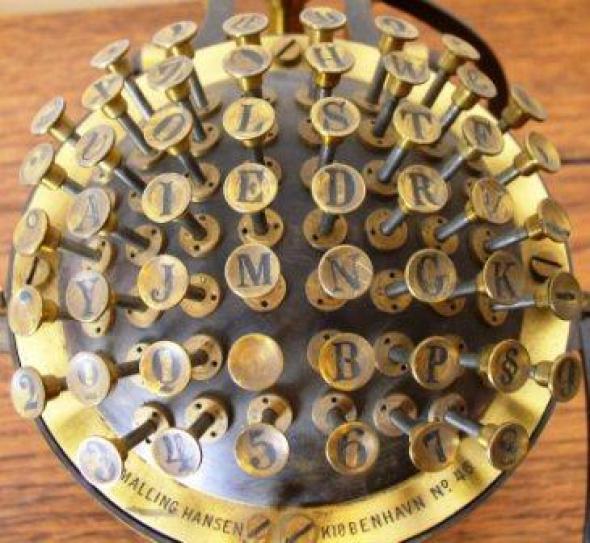

The story goes that people had trouble with early typewriters because commonly used letters were too close together on the keyboard; for fast typists, the letter bars would collide with each other and get stuck. QWERTY was designed in response so that frequent letter combinations are spread across the keyboard, and also to include in the top row all the letters in the word “typewriter,” for the benefit of demonstrations by salesmen who weren’t very proficient typists.

Early keyboard designers chose arbitrary sets of words and tallied up letter frequencies to propose ergonomic layouts. Every designer chose a different word list, and the process of counting letters was manual and time-consuming. Linguistically and ergonomically, QWERTY is no better or worse than most of the many competing early layouts, but it happens to be the one that caught on.

It’s easy to imagine the pencil-and-paper process used by those early keyboard designers. Even in 2014, most English keyboards on most devices still use QWERTY, just because enough typists have remained in the habit of it from one generation to the next. But despite the arbitrariness of the QWERTY layout, the rest of the modern typing experience is entirely a product of statistics and engineering. And the core of the modern typing experience starts with a modern dictionary.

The typing dictionary on your phone is no simple word list. This is a complex table, or series of tables, that stores not only entries for individual words but a large quantity of information about their likely usage. Any individual word carries with it information about part of speech, allowable prefixes and suffixes, statistical probabilities of common misspellings, and likelihood of its adjacency to particular words. Parsing technologies like spellers and grammar-checkers are built on top of these dictionaries, and they use the full set of lexical metadata to make corrections and suggestions as you type.

While earlier incarnations of my iPhone drove me crazy auto-correcting its to it’s and well to we’ll in the wrong context, more recent versions have gotten smarter at trying to predict which one you’ll want from context. In fact, modern typists are so reliant on auto-correct that there are entire websites dedicated to the rare cases where the technology fails.

The best typing technologies use your own usage to personalize your experience. QuickType, the native iOS 8 keyboard, supports not just one autocomplete suggestion but several. It’s nice for users to have options, but there’s greater value: By giving you multiple suggestions to choose from and seeing which one you select, the operating system is able to collect richer data about your usage patterns. These patterns are reflected in your modern dictionary. The more you use it, the better it gets.

Furthermore, because these keyboards learn as you type, the linguistic technology that supports them isn’t static. New entries get added to the dictionary as you use new words. The more text you make available, the more data you push to your dictionary. For instance, SwiftKey, new for iOS but already popular on Android, allows you to hook up your personal dictionary to your phone’s contacts and your Gmail, Facebook, and Twitter accounts. This means your friends’ names are spelled correctly out of the gate even if they’re named something rarer than John or Jane Smith.

Increasingly, these dictionaries aren’t even stored on your device. Many of the new iOS keyboards have been available on Android for some time and support personalized typing experiences across your devices. The dictionaries to support these personalized cross-device experiences are stored in the cloud, so they’re available for you right away when you log in to a new device.

Will we ever see the end of the QWERTY layout? Smartwatch and other wearable device manufacturers may be betting on voice recognition technology, but typing still has its advantages: It’s discreet, for one thing, and it’s not affected by background noise or music. If people’s excitement at having multiple keyboards on iOS is any indication, we’re going to be caring about the keyboards on our devices for quite some time to come.

Correction, Sept. 29, 2014: This post originally described the TiVO keyboard as not QWERTY. Some TiVO remote controls have QWERTY keyboards; the on-screen keyboard, however, remains alphabetical.