Ikea has a new catalog ad that tries to sell you on the idea of a “bookbook.” It’s a clever parody of Apple ads, promoting the advantages of traditional books, like “328 high-definition pages” with “pre-installed content” and “no cables, not even a power cable!”

But what I’m really interested in is where they got the name for their technological marvel, the so-called bookbook: It turns out that the process that gives us “bookbook” is the same one that gives us “do you like him, or do you like-like him?” and “do you want soy milk, almond milk, or milk-milk?” It’s called contrastive focus reduplication, and it’s pretty interesting.

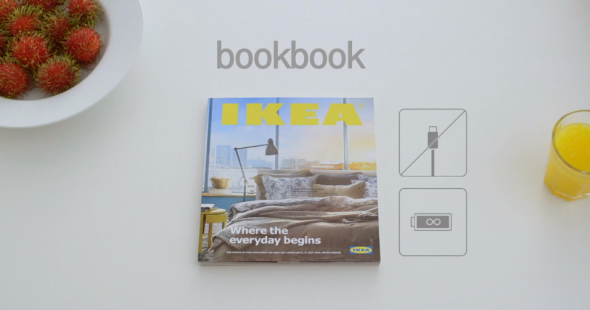

First, here’s the Ikea ad in case you haven’t seen it already:

Now, let’s go back to the fancy terminology. Reduplication is a way of making new words by repeating all or some of the original word. It’s found in a wide variety of languages, and for a wide variety of purposes. In Malay, for example, reduplication indicates more than one of something: buku is “book,” but buku-buku is “books.” In Swahili, on the other hand, reduplication indicates a repeated action: piga is “to strike” but pigapiga is “to strike repeatedly.” In Hebrew, reduplication of the last two consonants can sometimes indicate a smaller, cuter version, such as kelev “dog” becoming klavlav “puppy.”

English has a few different types of reduplication. There’s the reduplication used in word games and baby talk (hokey pokey, Humpty Dumpty, choo-choo). There’s shm- reduplication, indicating a dismissive attitude towards something (book, shmook; fancy, schmancy). And then there’s our old friend bookbook. What’s the reduplication doing here?

Here are several more examples of this kind of reduplication, taken from a linguistics paper known simply as “The Salad-Salad Paper“:

I’ll make the tuna salad, and you make the salad-salad.

Is he French, or French-French?

I’m up, I’m just not up-up.

That’s not Auckland-Auckland, is it?

My car isn’t mine-mine; it’s my parents’.

Oh, we’re not living together-living together.

What do they all have in common? Well, there are a variety of things that could be considered salad, for example: tuna salad, pasta salad, potato salad, and, of course, green salad. But only green salad is the prototype of salad, the most obvious example, the kind you’d think of by default with no other modifiers getting in the way. Salad-salad.

Similarly, something can be French without being prototypically French, up without being prototypically up (awake but not out of bed, for example), Auckland without being the Auckland you’d normally think of, or mine without being permanently mine. It’s called contrastive focus reduplication, then, because it lets us focus on the most prototypical version in contrast to all of the less prototypical alternatives.

What about living together? Well, there’s a minor exception to the prototype trend: Certain reduplications, such as like-like or living together-living together can also give rise to a “value-added” interpretation, especially if you pronounce it with a tone of voice that suggests you’re raising your eyebrows. For example, depending on the context, living together-living together can mean either more or less than normal:

A: I hear you guys are, um, living together now.

B: Well, we’re only living together-living together. [Prototypical]

B: Well, we’re not living together-living together. [Value-added]

So when Ikea introduces its new catalog with the line, “It’s not a digital book, or an ebook: it’s a bookbook,” it’s invoking the broadest possible set of books and then using contrastive focus reduplication to emphasize the prototypical qualities of their example. But there’s a certain amount of irony, since a glossy catalog is in fact a less prototypical instance of a book than, say, a paperback novel. You could say it’s prototypical, I suppose, but it’s not prototypical-prototypical.