Beatboxing doesn’t sound a lot like language and, well, that’s sort of the point. It’s supposed to be an a cappella version of the percussion section, not a coded set of lyrics. However, since the human vocal tract—including the palate, tongue, teeth, and other mouthparts—is used for both beatboxing and speaking, linguists at the University of Southern California wondered to what extent beatboxers draw on actual speech sounds. To find out, they put a professional beatboxer in a real-time MRI machine. The resulting cross-sections of the beatboxer’s mouth and throat show a range of sounds, all linguistic, but only some of which are found in the beatboxer’s native language (in this case, both English and Spanish).

Some examples of relatively English-like sounds are the B-like sound of a kick drum (written [B] in Standard Beatbox Notation, or SBN), a K-like rimshot on a snare drum (SBN [k]), and a T-like sound that results when hi-hat cymbals are struck while in the closed position (SBN [t]). To hear what these effects sound like and how to produce them, check out this tutorial video by beatboxer Fat Tony. Although he wasn’t the beatboxer scanned in the study, notice how he starts with the English-y sound and then coaches the viewer to build up pressure so that the sound gets an additional puff of air (for the kick drum) or bit of friction (for the snare and hi-hat) as it’s released:

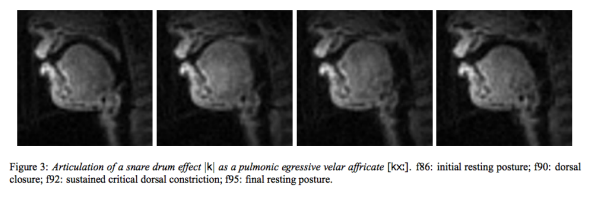

But what exactly is happening when we produce, say, the snare drum effect? Here are the MRI images of that sound from the study:

Images courtesy of Michael I. Proctor, Shrikanth Narayanan, and Krishna Nayak

In the first picture, the tongue is in a neutral position, so the air flows smoothly out along the dark open part and doesn’t produce any noise. The tongue then raises up to touch the soft palate, near the back of the roof of the mouth. In the third image, the beatboxer continues to hold his tongue against the soft palate while building up air pressure behind it, as indicated by the slightly bigger space behind the tongue, before releasing it along with the extra portion of air that follows the [k] sound. Finally, the tongue ends up back in the resting position shown in the final image.

Here’s an MRI video from the study showing the beatboxing scans paired up with the sounds:

A second group of beatboxing sounds that the researchers noticed are those that aren’t found in English, and which the beatboxer would have to have learned with more conscious effort. Here’s Fat Tony again demonstrating one such sound. In this case, he’s doing what’s known among linguists as a lateral click, because you use the side of your mouth. He also digresses briefly into the “block click” at 0:20, which is known among linguists as a post-alveolar click based on the technical name for the roof of the mouth:

Clicks are most commonly found in several languages of southern Africa, including KhoeKhoegowab, a Khoisan language spoken in Namibia, Botswana, and South Africa. Starting about a minute into the following video, we can see the post-alveolar or “block” click, denoted onscreen with an exclamation point (!), and the lateral click, denoted with a double slash (//), in addition to two more clicks that weren’t in the above beatboxing video but I’m sure have been used by beatboxers at some point:

What’s interesting is that you don’t have to speak a language with clicks in order to happen upon them as a beatboxer. Since there are only a limited number of ways that the human vocal tract can move around, chances are that when you start experimenting with different sounds you’ll end up producing some that are used by a language somewhere in the world, even if it’s not your own.

Another way to see that actual speech sounds are used in beatboxing is to plug a sequence like pv zk pv pv zk pv zk kz zk pv pv pv zk pv zk zk pzk pzk pvzkpkzvpvzk kkkkkk bsch into Google Translate for German and ask Google to read it aloud to you. The result sounds remarkably like a beatboxer. Here’s a video demonstration:

Why German? Well, for many languages, including English, Google’s speech synthesizer reads a lone consonant (or group of consonants) as if there were a vowel next to it, so “b” by itself would be read as “buh,” instead of “b” with a puff of air. The addition of a vowel sound produces more accurate results when guessing at unfamiliar English words, but it’s not as good for beatboxing. The Google synthesizer used to omit such vowel sounds in German, however, making it a better beatboxer, if less Teutonically fluent. (Unfortunately, Google Translate now reads the letter names instead of producing the sounds in isolation, even for German, effectively destroying its beatboxing ability.)

What’s more, German has a K-like sound that’s produced with a tiny open space at the back of the mouth, as in Bach and achtung, an effect that isn’t typically found in English (except in Scottish words like loch) but is useful for the percussive noises of beatboxing. And if Google Translate had the ability to read aloud a language like KhoeKhoegowab, Xhosa, or Zulu, we could even get the clicks!