A version of this post ran on The Week:

(Bettmann/CORBIS, Stuart C. Wilson/Getty Images)

March 28, 2014, is the 160th anniversary of Britain declaring war on Russia to formally start the Crimean War. The war was fought by Britain, France, and the Ottoman Empire against Russia, mainly to curtail Russia’s presence and ambitions in the Black Sea and Eastern Europe. It lasted until 1856, and was fought in several places, not just Crimea. But it’s best remembered for just one battle, a battle that was vaunted as glorious and heroic by the side that lost it (but won the war)—and that has left us with some misquotations, three articles of clothing, and some lessons in accidental and deliberate miscommunication.

Here is your pocket guide to what we owe to that battle.

Balaclava

(Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images)

The battle we are speaking of was the Battle of Balaclava. Balaclava (also spelled Balaklava) is a bay south of Sevastopol (its name is thought to come from words meaning “catch fish”). The battle was fought on October 25, 1854, and it was already plenty cold there at the time, so the British soldiers wore knitted pull-over head coverings. These came to be known as Balaclava helmets, and now they’re just called balaclavas. They’re associated more with crime than with Crimea these days.

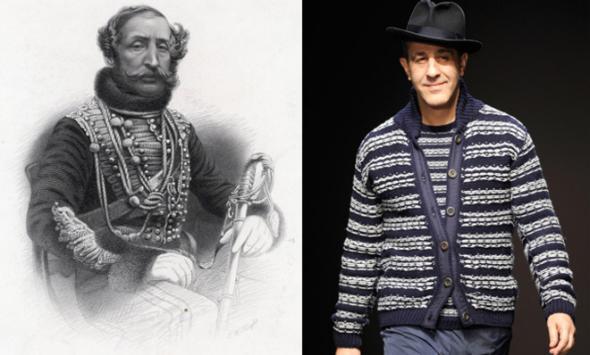

Cardigan

A noted hero of the Battle of Balaclava was James Brudenell, 7th Earl of Cardigan. British officers in the Crimean War wore knitted waistcoats (again: it was not warm there at the time), and Brudenell became quite the famous figure after the war, so the buttoned sweater vest came to be named after him. Once associated with a dashing cavalry hero, cardigans are now seen on bookworms and grandmothers.

Charge of the Light Brigade

(Bettmann/CORBIS)

What was the Earl of Cardigan famous for? A suicide mission in a lost battle. He led a cavalry brigade, the Light Brigade, made up of units of dragoons, lancers, and hussars. He was given a poorly written, badly relayed order, which was not the only time that happened during that battle; in fact, just about everything to do with the Battle of Balaclava was a showpiece of sloppy communication and misunderstanding. He was supposed to be chasing after a retreating artillery battery. Instead, the order he got was to make a frontal assault on a different artillery battery—one that was not retreating at all, and bombarded the Light Brigade quite effectively. Of some 666 men, 118 were killed, 127 were wounded, 60 were taken prisoner, and only 195 still had their horses at the end.

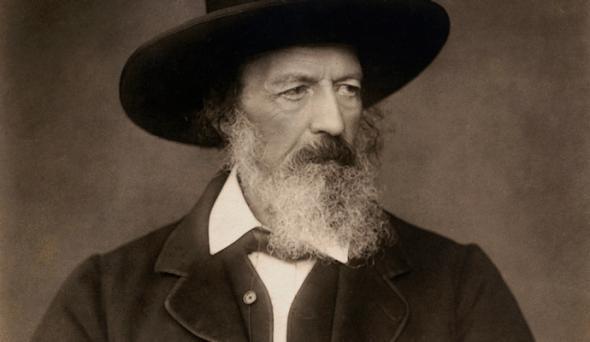

On the other hand, the insane bravery of the charge unnerved the Russians. And the Light Brigade were immortalized by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, in his poem “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” which portrayed the charge as more doomed than it was, thanks to a mistaken news report. When given a correction, Tennyson refused to change his poem. Why would he? It sounded better his way.

Ours is not to reason why, ours is but to do or die

Perhaps it’s plain justice on Tennyson that the most-quoted line from his poem is typically misquoted. You have surely heard people say “Ours is not to reason why, ours is but to do or die” in sardonic stoicism about orders from upper management. Here is the original as Tennyson wrote it:

Theirs not to make reply,

Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to do and die

Raglan

The poorly written orders that led to the misguided charge came from FitzRoy Somerset, 1st Baron Raglan, overall commander of the British forces. He was a senior career soldier and sometime politician; he had lost his right arm at the Battle of Waterloo. It is likely because of his dis-armed state that he preferred a coat with the sleeve fabric extending to the collar rather than stopping at the shoulder. That style of sleeve came to be called a raglan sleeve, and it’s usually seen on casual wear and sportswear now. I know when I was a teenage boy in the ‘80s I had no idea my T-shirt had sleeves named after a war “hero” who botched his last assignment and died of dysentery before the war was over.

Thin Red Line

(DoD/Corbis)

Before the charge of the Light Brigade there were two more successful maneuvers. One was the charge of the Heavy Brigade, and before that was a standing defense by the 93rd Highlanders. The Russian cavalry were charging, and the Highlanders were put in place as the first line of defense. Their commander, Colin Campbell, 1st Baron Clyde, had a low opinion of the Russians and lined his men up across a hilltop only two soldiers deep rather than the usual four, and told them to die rather than move. William H. Russell, correspondent for The Times, jotted hastily as he watched: “The Russians dash at the Highlanders. The ground flies beneath their horses’ feet; gathering speed at every stride, they dash on towards that thin red streak topped with a line of steel.”

The Highlanders fired as the Russians approached, inflicting damage. But the real reason the Russians retreated was that it was so crazy to have just a thin line of soldiers there—the Russian commander figured they had to have a much larger force lurking behind them. Russell’s description of a “thin red streak topped with a line of steel” came to be shortened to “thin red line,” which entered popular usage as a bit of old-style sloganeering for the British army. It is echoed in “thin blue line,” a term for police in American cities and the title of a documentary by Errol Morris.

Valley of death

Another quote from Tennyson’s poem is “Into the valley of Death / Rode the six hundred.” This “valley of Death” is undoubtedly influenced by the 23rd Psalm’s reference to “the valley of the shadow of death.” But don’t give the credit to Tennyson; the soldiers in the battle called it that. And after the battle, a photographer named Roger Fenton took a famous picture of it, the road strewn with cannon balls—how could anyone have survived that? When he put the picture on show in England, he improved the title to The Valley of the Shadow of Death.

But actually, he took two photos. In one, the road is strewn with cannon balls; in the other, the cannon balls are mostly in the ditches on the side of the road. Fairly recently, a noted documentarian examined the photos closely and determined that the one with the balls in the ditch was taken first. Fenton may have had assistants move balls onto the road because it looked better. And who was the documentarian who figured that out? Errol Morris again.

So there we have it. A battle characterized at the time by sloppy orders, and afterwards by misrepresentation, has now been memorialized in misquotations and in articles of clothing that to most people carry no suggestion of the military heroism they were named after. And are we supposed to be surprised when there are errors, miscommunications, and misapprehensions involving Crimea now?

More from The Week:

How optical illusions trick your brain, according to science

What would a U.S.-Russia war look like?

How to develop a photographic memory in 4 easy steps