As anyone who has ever graded a stack of freshman composition papers can attest, over the course of this Herculean task, one will inevitably wonder what exactly standard usage really is. I, for one, began to doubt my very prepositions.

Indeed, as the editors of The Chicago Manual of Style note, “Among the most persistent word-choice issues are those concerning prepositions. Which prepositions go with which words?” Putting aside the quibble some linguists have with the very definition of preposition, why is it that these tiny particles of grammar give even the most eloquent native speakers such a hard time?

Part of the answer is the many nuanced supporting roles that a single preposition can play: to be on the ground, to be on medication, to be on time, and to depend on someone each exploit a different sense—spatial, temporal, or abstract—of on. This semantic repertoire is further complicated by the preposition’s seemingly inconsistent behavior: We can do something in March, in 2014, but we have to do it on Monday. And then there’s the fact that a given word can be seen stepping out with any number of prepositions: we inquire into, inquire of, and inquire after. “A preposition,” the saying goes, “is anything a squirrel can do to a log.” Not strictly true, but it does illustrate the promiscuity that this part of speech encourages.

What’s more, preposition use shifts over time. Of, for instance, was also used through at least the 1800s to mean something akin to from, as in this bit from an 18th-century diary: “We had nineteen Bottles and a Pint of the Tub.” Similarly, in was often used where we now use on: in the throne, in the top of a mountain, to make an impression in someone. And while we no longer speak of something happening “on a sudden,” people once did—well into the 1950s. Such shifts are endemic to language, of course, but they only add to the confusion over how to handle a preposition.

It was about the time I first became acquainted with the freshman comp essay, though, that I began to notice the dramatic influx of on among the prepositions in the papers I was grading. That is, it seemed to appear as a kind of universal stand-in, the preposition most likely to be pressed into service when uncertainty arose. What I have come to think of as “on substitution” can be divided into two major categories. The first is cases where on has come to be more-or-less interchangeable with the more prescribed preposition—so that to have an opinion of someone can be rendered as “on someone” and to ask a question about something becomes “on something.” The second category involves uses of on that are not quite rare bird sightings, but are yet to be broadly accepted. It’s not unheard of, for example, to encounter a sentence like “I gave her advice on email” or “I can offer an explanation on why that is,” though via and for (or as to), respectively, are far more conventional choices.

Among my students, I would even encounter on when the writer was clearly unsure how to phrase an idea but felt that something like a preposition was in order. “You have to constantly be regaling on the same things night after night,” one wrote. “It was a competition on which one was the best,” observed another. And I would so frequently see phrases like a recap on X, arguments on why Y, and our perception on Z, that I questioned whether my own formulations were too limited. (For what it’s worth, I would replace the on in these cases with of, for, and of, respectively.)

To be fair, it’s not just among college freshman that on has annexed territory once held by its fellow prepositions. In Season 2 of The Wire, Nick tells his uncle that the Greek wants “to meet on Ziggy.” A news correspondent on NPR observed that someone was “ambivalent on the issue.” In a linguistics podcast I listen to, one of the hosts asked, “What else did they have to say on that?”

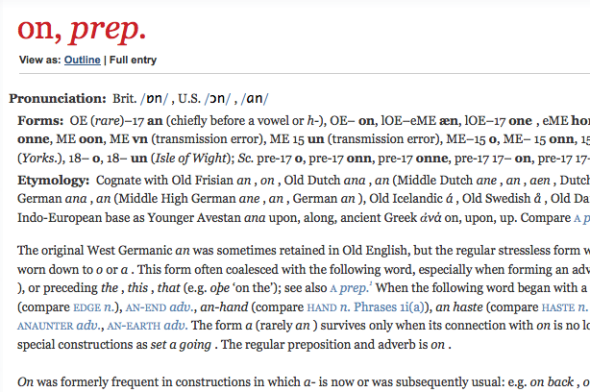

On, to be clear, has always been in heavy rotation. It currently ranks as the sixth most frequently used preposition in the English language, and during the several centuries that Old English was spoken it may have been first. Also, it had great range. Not only could one use it in the ways we do today—to say the troops were on the march and the enemy on horseback on Good Friday—but you could also use it in ways that now typically require about, in, at, to, into, from, of, or with. Gradually, though, as Old English gave way to Middle, the once admirable versatility of on diminished. Of course, this took some time. In Shakespeare’s era, for instance, one could still be fond on someone and arrive on a moderate pace. And in both American and British newspapers of the early 1700s, one speaks of poring on books.

But not so as we move to the literature of the 19th century and into the 20th, where we see Henry James, and then Edith Wharton, and then Ernest Hemingway having little to do with the on of earlier generations. Their characters talk of and, increasingly, about things, but rarely, if ever, on them. They know, tell, and say of and about things, but, again, not on them. These were lean times for on, at least in print. Typical newspaper headlines from the period look like the following:

VIEWS REGARDING THE QUESTION OF SECESSION (1860)

THE AMENDMENT OF THE CONSTITUTION REGARDING SUFFRAGE (1869)

BERLIN IS HOPEFUL REGARDING THE FUTURE (1933)

Something happened to American newspapers, though, about the time of World War II. Headlines started to look like this:

ARNOLD REASSURES AD MEN ON POLICY (1941)

AIDES GLOOMY ON TALKS WITH BEGIN (1978)

EUROPEANS HOPEFUL ON GROWTH (2004)

For the first 77 years of the New York Times’ daily printing, regarding appeared in 4,641 headlines; from 1938 until today, it has appeared in only 525. On the other hand, on’s headline appearances have shot up precipitously in that same period of time.

Perhaps, as newspapers grew less formal, more conversational uses of on (which were always lurking) became hard to resist. And with headline real estate scarce, on is a tempting alternative to regarding and about. Surely this on substitution had an effect, eventually, on the column inches below the headlines, and on readers—not to mention those who only glimpsed the headlines in passing.

So, are headline-writers, those poets of compression, responsible for how freshman comp students write? It’s impossible to say for sure. But it’s something to think on.