What tools does a grammarian need? A brain helps, and so does a computer, but surely one of our most essential tools is some kind of diagramming system. How can we think about a sentence’s structure, after all, without displaying it visually? Geographers have maps; mathematicians have equations; composers have musical notation; economists have graphs; and grammarians have trees.

It wasn’t always so. Grammarians spent several thousand years trying to think about syntax without the help of diagrams, but it was hard and they didn’t get very far into structural details. It was only in the early 19th century that an American, Stephen Watkins Clark, achieved the breakthrough for which he has received virtually no credit (how many of us even know his name?). In 1847, he published the idea of drawing a kind of map to show a sentence’s physiology. Admittedly, his implementation of the idea wasn’t so great, because it involved rather clumsy bubbles. Here’s an example, applied to a typically worthy sentence (the diagram comes courtesy of Google Books):

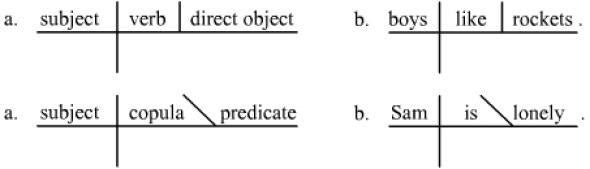

Just 30 years later, Alonzo Reed and Brainerd Kellogg, possessing typical American marketing skills, created a more appealing version using lines instead of bubbles, like this one generated by an online parser:

For a long time, sentence diagramming flourished throughout the American school system, and, despite being condemned as a useless waste of time in the 1970s, it still persists in many schools. Indeed, it spread well beyond the USA, and so a very similar system is taught in many European countries (though not, alas, in the United Kingdom). For example, schools in the Czech Republic teach sentence diagramming so successfully that researchers are investigating the possibility of including school children’s analyses in a working tree-bank of analyzed sentences.

In Europe, some linguists saw an opportunity to make the diagrams even better. The classic example is by the French linguist Lucien Tesnière, who applied ideas that were already circulating in the Linguistic Circle of Prague to school grammars. His innovation was the stemma, which looked rather like Reed-Kellogg diagrams but culminated in a single top node for the root verb. Here’s what it looks like using the same sentence:

This diagram was also generated by an online parser (which, like most parsers, makes mistakes—what happened to the first word, Our?). This parser is part of a Danish website for applying current linguistic theory to the teaching of grammar in schools—surely just the kind of development that academic linguists should celebrate.

The UK, where I live, had a home-grown alternative to Reed-Kellogg (invented by John Collinson Nesfield in the late 19th century, and still in use in my school during the 1950s), but it used columns rather than diagrams. I have no idea why we didn’t implement Reed-Kellogg, but we didn’t; and worse than that, we started a big international campaign against all grammar teaching (with or without diagrams) in the first half of the 20th century. Unfortunately, America followed and the disease spread throughout the English-speaking world and beyond.

As we struggle to rebound from the effects of that disaster, it’s worth honoring Stephen Watkins Clark and his bubbles! Nearly two centuries later, where would modern linguistics be without him? And even more importantly, where would those countless generations of bright school-kids (and teachers) have found their fun?

A version of this post originally appeared on Language Log.