There are some myths about infancy that, like some infants, will never, ever go to sleep. No matter how many times they are put down, it’s just a matter of moments before, in some far forgotten corner of the Internet, they start wailing once again.

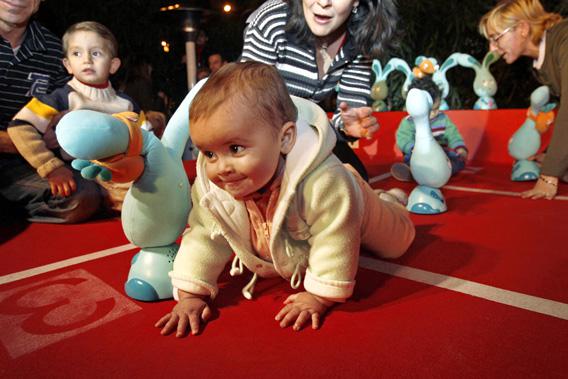

Among the most pernicious and persistent is the idea that crawling matters. If your baby does not crawl, this theory suggests, she will be damaged in some way. Hands-and-knees crawling knits together crucial neural connections.

It’s the sort of idea that seems like it should be true. After all, Americans are now a yoga-going, post-Cartesian people. The mind and the body are no longer seen as separate spheres. The theory that crawling helps shape the brain is intuitively correct.

Only intuitively, though.

The prominence of crawling in the modern parental mind can be traced to Arnold Gesell, the psychologist who established the first developmental stages a century ago. Gesell thought crawling was a fundamental part of motor development, and ever since he enshrined it in his developmental charts, it has never gone away. Today it is easy to find occupational therapists who tout the neural importance of crawling. And there are still physical therapies that simulate the cross-crawl, and thus “restructure” the brain, despite the American Academy of Pediatrics declaring the idea worthless.

But there is no scientific study that links not crawling to any negative outcomes. None. (Children with developmental problems are more likely not to crawl or to crawl asymmetrically. But children with developmental problems are more likely not to do lots of things. It isn’t not crawling that causes the problems.)

Even going back to scientific studies is unnecessary, though. The theory that crawling is crucial is deeply provincial. It overlooks history and culture. For centuries, American and European children grew up under heavy, bulky clothing that strangulated all movement. Even the lighter clothing babies wore was too long for a baby to get traction; they literally couldn’t crawl. Besides, before the Enlightenment, no parent wanted a child to crawl. Crawling was considered bestial, a godless act. Even today, there are cultures where crawling is considered too dirty and dangerous—infants who try to crawl are carried instead.

And of course, many children never bother to try. Every parent knows a child who skipped crawling and went straight to walking or only scooted instead. Studies confirm this. There are many of these children, and they do just fine. Therapists who stress the importance of crawling talk about how it promotes socio-emotional and muscular development, how it encourages independence, how it exposes infants to challenging new stimuli—all of which is crucial. That may be true. But there’s no evidence that crawling alone does that. Motor development unfolds along many paths, but a century after Gesell, the myth of that one true way persists.

And it will never go away. Since it can never really be disproved, it can never really be dismissed. And thus it may be safer to believe in it—just in case. As a therapist says in an article in Parenting magazine, “Though there’s little scientific proof that crawling is important, there are plenty of experts who believe it is—so what’s the harm in doing tummy time and letting nature take its course?”

Indeed! Why not be worried when you could be worried?

***

Nicholas Day’s book on the science and history of infancy, Baby Meets World, from which part of this post was taken, was just published. His website is nicholasday.net. He is @nicksday on Twitter.