In 1914, a baby named Charlie Flood was born, and if you do not know his name, it is not because his infancy was uneventful: It is reported that, at the very least, some quicklime burned his face and a buttonhook snagged on his tongue.

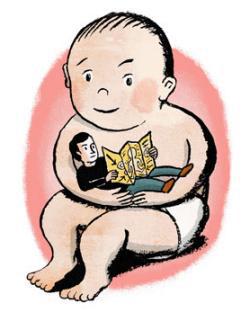

How do we know these things a century later? From his baby blog. Wait—I mean, his baby book. A new accoutrement of parenthood, coming into existence just a few decades before Charlie Flood himself, baby books were where mothers—and they were almost always mothers—recorded the mundane, wondrous details of infancy. These books didn’t just prefigure the modern baby mania of the Internet, they also marked a significant moment: For likely the first time in history, it became common for a whole population to write down their random thoughts about their babies. The baby books, like baby blogs today, were a new genre that encouraged parents to pay more attention to every tiny detail of infancy.

“They are really early baby blogs,” says Janet Golden, a historian at Rutgers-Camden, who read the baby book of Charlie Flood and those of countless other babies in her research on the history of babies in modern America. Sometimes fancy bound volumes, often cheap, thin-papered pamphlets, baby books went mass market in America beginning in the 1910s, and only became more popular over the succeeding decades.

It’s not as if no one had taken notes on a baby before, of course. Some scientifically-minded parents (mostly fathers this time, including Darwin) kept detailed accounts. And the child study movement encouraged mothers, for the sake of scientific progress, to bloodlessly record every nervous twitch and bowel movement. But the parents who kept baby books were not doing research or refining the science of child care. They simply wanted to remember these wondrous beings in their midst.

Why did baby books appear around the turn of the 20th century? Well, partly because parents could finally count on their babies surviving. Sanitation improved, medicine got a (small) clue, and infant mortality rates dipped sharply. Not long before, many parents had set aside money in case they needed a postmortem baby picture. Now parents were taking photos of their very much alive babies with Kodak Brownie cameras. “It’s a sign that, yes, they expect the baby to live,” Golden says. And so expectations shifted. “People become very concerned with education and the future,” Golden says. Incredibly, there are advertisements about saving for college as early as the 1920s.

These advertisements are the other reason for the appearance of baby books. The books began as a way for the upper class to record gifts of gold jewelry and silk dresses. But they were quickly down-marketed: Businesses discovered that babies are a wonderful excuse for consumption, and they helpfully padded the pages of baby books with advertisements for all manner of things that that no baby should be without. The buy-baby-buy phenomenon of modern consumer culture is not actually modern. It worked back then, too. The cheap-to-print baby books demonstrate, Golden says, “just how remarkably effective manufacturers, advertisers, insurance companies are in getting their brand names out there. Even poor families give the brand names: the Borden’s milk, the Carnation milk. They go out and buy baby clothes, because they’re ‘hygienic’ and ‘sterilized.’ You really bring people into consumer culture.”

As you see parents learning to parrot the language of expertise, you can observe the origins of how we think about babies today. The earliest baby books were obsessed with metrics: A good mother was supposed to measure and weigh her child constantly. “Baby books have advertisements for renting baby scales,” Golden says. “Or people go into town and borrow the butter scale and put the baby on it.” It was only after World War II that parents paid less attention to raw numbers and more attention to when their children point for the first time. Guided by the advice of Arnold Gesell, and then Spock, they unconsciously began to think in developmental terms, like us.

And they slowly became more safety-conscious, more paranoid. “There are some wonderful accounts in those early baby books of babies having accidents and getting injured, which parents in the pre-war period find very amusing,” Golden says. (See, epically, Charlie Flood.) In the post-war era, those vanished. “I’m not convinced that babies stopped bumped their heads, or falling out of high chairs, but culturally you’ve learned that you don’t record that—that becomes evidence of abuse.” Physical discipline was once so prominent that baby books had headings for “My First Discipline.” In 1908, a mother wrote of her month-old infant: “Baby received some discipline this morning. She refused to go to sleep before breakfast and also refused to be good.” By the post-war period, these entries also vanished.

You can also see the origins of the contemporary germophobic parent in early baby books. Advertisers were happy to inform mothers of the new and improved products to make mothering safer, cleaner, more sanitary. Parents could buy bibs that read, “Don’t Kiss Me.” Kissing, needless to say, spread germs.

Which is not to say that the mothers in these books trembled before the experts. The popular 1930 Book of Baby Mine informed parents that “all young infants are extremely nervous so avoid exciting them, playing with them, or handling them too much.” But many mothers nonetheless wrote about playing with their babies—in direct contradiction to the advice given in the book they were writing in. Their disobedience is heartening. The history of child rearing tends to be written by the experts, but the baby books record the gap between what was prescribed and how mothers actually mothered. They’re not unlike blogs today: They let the writer express her defiance. As Golden says, “People will say, well, they say you shouldn’t spank your child, but I spank my child; they say you shouldn’t co-sleep but I co-sleep. Everyone has this sense that, yes, there’s an orthodoxy but I’m doing something a little different.”

They’re like blogs in another sense, too: They give us a record of the very first child. We know far less about the life of a second child; we know almost nothing about a third or fourth. Any parent today can identify with this problem; any iPhoto archive is evidence of it. As Golden says, “By the time the other ones come along, you just don’t have the energy. Rolling over just isn’t as exciting.”