Fellow parents! Are you at a loss as to how to encourage your child to use the potty? Have you had enough of the Cheer for Me Potty and Where’s the Poop? Perhaps the problem is that you have not read The Care and Feeding of Infants, by Frederic H. Bartlett. You should be ashamed. But it is never too late.

If you can, start training your infant to have a bowel movement in the chamber each morning at the age of one month. … Place the chamber on your lap … and hold the infant over it. … Insert about two inches into the rectum, a tapered soap stick, keep it there from 3 to 5 minutes… The movement will usually occur under this stimulus. If you keep this up with regularity, a daily bowel movement will probably result.

Probably!

The Care and Feeding of Infants was published in 1932. In the previous few decades, child rearing, as dictated by experts, had gone from indulgence and sentimentality to a task that should be conducted without mercy. Babies should no longer be babied; they should be bent to parental will. And the sphincter of the infant was not exempt. It was as important as anything else, if not more.

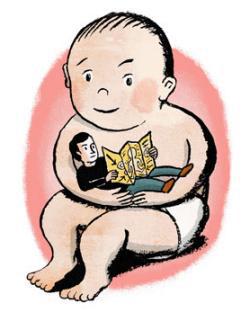

Illustration by Robert Neubecker

The change happened in a hurry. The 1914 edition of Infant Care, the U.S. Children’s Bureau guide to child care, recommended that toilet training begin by the third month, but mothers were told that making their baby tense would make matters worse. They should be gentle and laugh, and they should not scold. Their child should be relaxed, for obvious reasons. By 1921, though, there was no more laughter, and there was no more talk of relaxation. In their place, there was rigor and firmness and discipline. Behaviorism, the idea that everything in infancy can be mechanically learned, was ascendant.

But within less than 20 years, incredibly enough, the conventional wisdom would shift yet again, this time under the influence of Freudianism. According to this interpretation, babies were said to take deep sensual pleasure in vacating their bowels, and parents who toilet-trained too early were inhibiting the ability of their children to experience pleasure. Right now you are saying, but bowel movements make my baby miserable. Yes. As with much midcentury Freudian child-rearing advice, a little experience at home actually caring for babies would have cleared up a lot of confusion.

But never mind that: Too-early toilet training posed the risk of permanent lifelong damage. “In extreme cases,” according a 1947 book, “one becomes parsimonious, stingy, meticulous, punctual, tied down with petty self-restraints. Everything that is free, uncontrolled, spontaneous is dangerous.” The anthropologist Geoffrey Gorer freely attributed the Japanese character to the early toilet training of Japanese infants—apparently forgetting that many American infants had been trained in much the same way only a couple of decades earlier.

Such whiplash-like reversals, of course, never end, as even in recent years very early toilet-training has come, once again, in vogue. A rare source of sanity is the education professor Celia Stendler, who in 1950 surveyed the previous 60 years of wildly vacillating child-rearing advice in women’s magazines. Instead of pounding in her head with a soap stick, she somehow emerged with among the wisest words ever written about caring for baby. Her language is filtered through midcentury Freudianism, but it is no less moving for it.

“What we can do,” she concluded, “what certainly needs to be done, is to help parents develop insight into their own personalities in the hope that they can more intelligently approach problems of child rearing. No trend in this direction has been noted in the literature examined.”