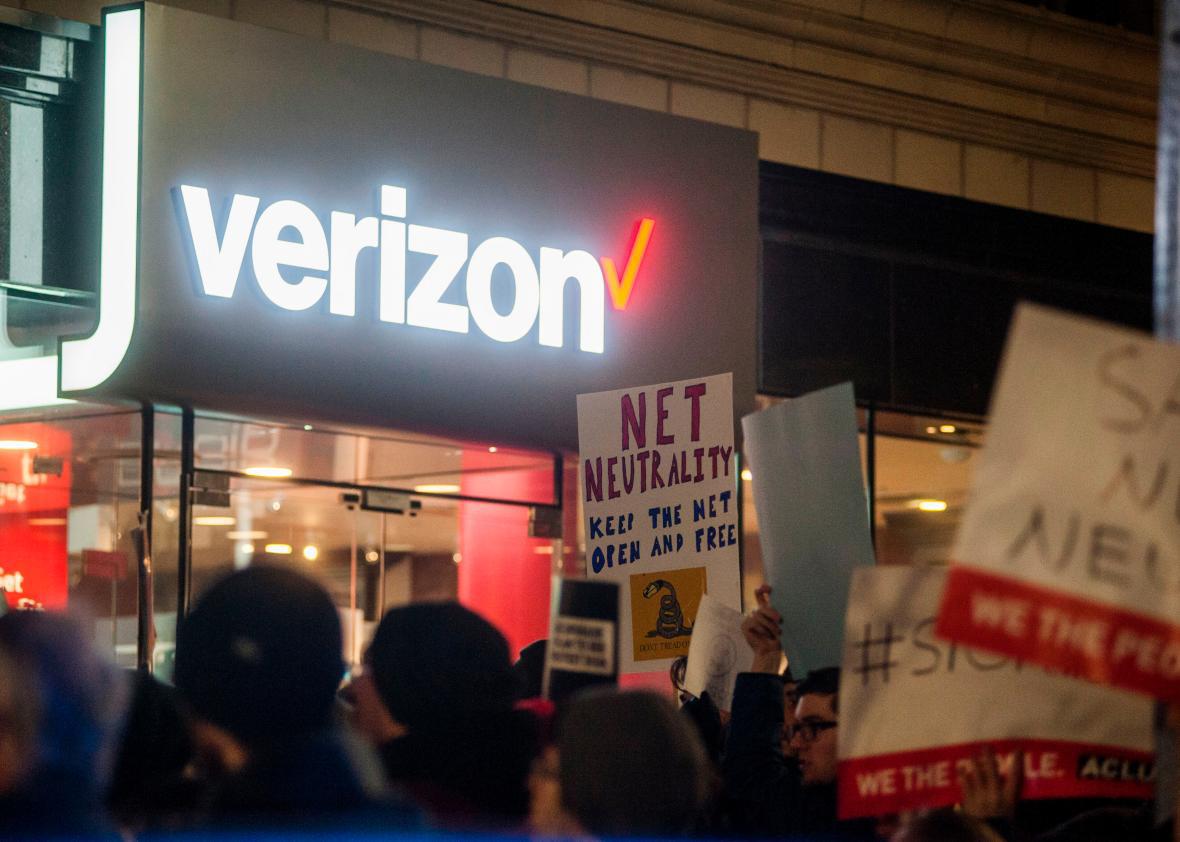

There are only three days left until the Federal Communications Commission votes on whether to repeal its network neutrality protections, the Obama-era rules that prevent internet providers from blocking and throttling connections to the internet or charging websites to access users. The FCC is currently majority-Republican and the agency is expected to vote for the repeal, meaning that by as early as January 2018, the net neutrality rules will be off the books and internet providers could start to charge websites for faster lanes or discriminate against content vis-à-vis connection speeds however they please.

When the FCC creates rules, it seeks comments from the public. The comment period on the network neutrality proceeding, proposed by Trump-appointed FCC Chairman Aji Pai, has amassed more public input than any policy in the agency’s history, with about 22 million comments submitted. But this process has been dogged by seriously troubling irregularities. Though there have been calls for the process to be delayed as a result—including from one of the FCC’s Democratic commissioners—“the vote will take place as scheduled,” an FCC spokesperson told Slate in an email. “The Commission sought comment on these issues months ago and has carefully reviewed the facts and the law.”

That may be true, but the docket where the FCC has solicited public input has been saturated with fraudulent comments in favor of repeal—from bots, Russian email addresses, stolen identities, and even dead people. There was also a cyberattack on the comment system, an incident currently under investigation by the Office of Government Affairs. Someone, or maybe several someones, really wants net neutrality gone, and has gone to great and shady lengths to push along its demise.

The net neutrality repeal process has been so fraught, however, that it’s been hard to keep up with the running list of snafus and trickery. So here it is:

- In May, the names people who recently died were found to have commented posthumously in favor of the FCC’s plan to repeal the network neutrality rules.

- 444,938 of the comments came from Russian email addresses, and 1.74 million comments in total came from outside the U.S. Only 25 of those emails from outside the U.S. were in favor of keeping the net neutrality rules.

- Thousands of comments from stolen identities have plagued the FCC’s system, which New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman’s office helped uncover with an investigation and an online tool with which people can check to see if a comment was submitted under their name.

- Many people’s names appeared thousands of times in the FCC’s net neutrality docket, and 94 percent of the comments appeared to be duplicates and were submitted multiple times.

- In May, the FCC said its comment system went down due to “deliberate attempts by external actors to bombard the FCC’s comment system with a high amount of traffic,” an attack often referred to as a DDoS attack, which the Government Accountability Office is now investigating. According to a letter from two members of Congress who called for the investigation, the FCC hasn’t “released any records or documentation that would allow for confirmation that an attack occurred.”

The public comment window is a critical part of how federal agencies ensure they’re acting in the interest of the public. Without a fair and reliable way for people across the country to engage in how the FCC crafts its federal policies, the only ones who would get a chance to have a say would likely be corporate lobbyists, legislators and bureaucrats, and professional advocates. Thousands of polices are promulgated each year through regulatory agencies, which are much more productive at policymaking than Congress, and the public comment process is the primary way people who are impacted by these rules can engage in the conversation before policies are finalized.

The fact that the FCC is moving forward with its vote to rescind the network neutrality rules despite a seriously troubled public comment period sets a dangerous precedent for federal rulemaking in general. Other agencies, like the Food and Drug Administration or Environmental Protection Agency, could follow the FCC’s lead and move forward with even more sweeping rule changes without a fair public comment process. And federal agencies, which are not governed by elected officials but rather appointees, could lose one of their core conduits for communicating with the American public. And that means the fallout from moving forward with Pai’s proposal, without pressing pause to make sure the public has had a fair turn at getting to voice their concern over or support for changing the open internet rules, could box Americans out of an important corner of democratic life.