Facebook made it possible for companies and campaigns to target advertisements to racists users. But when it comes to advertising an event aimed specifically at fighting racism, well, that’s a different story.

The group Portland Stands United Against Hate held an anti-racist march in Portland, Oregon, on Sept. 10 to counterdemonstrate against an event the same day organized by the right-wing group Patriot Prayer, which has been convening rallies in areas known to be hubs of liberal politics, like Berkeley, California, San Francisco, and Seattle. The Southern Poverty Law Center says that in the past, at least, Patriot Prayer’s rallies had “the clear intent of attempting to provoke a violent response from far-left antifascists” (though Joey Gibson, the founder of Patriot Prayer, says his recent events are all about promoting nonviolence).

Jamie Partridge, one of the lead organizers of Portland Stands United Against Hate and a retired postal worker, tried to promote the anti-racist counterevent on Facebook by buying ads that local Portlanders would see. The demonstration, titled, “Rally/March Against White Nationalism,” is described on its Facebook event page as an effort to “confront a white nationalist gathering in our town.” According to the event page, Portland Stands United Against Hate was in contact with the Portland Police, and the “permitted” event was “committed to community safety and protecting marginalized communities.”

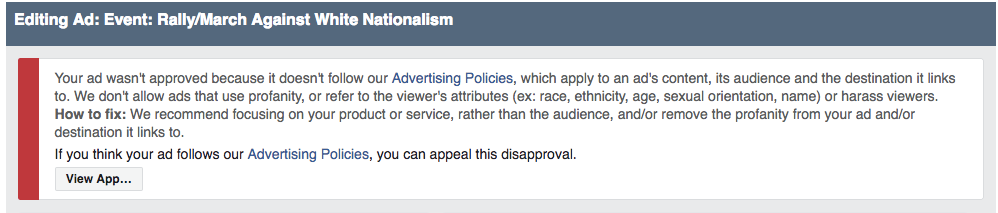

On Aug. 29, the ad promoting the event was approved. But just two hours later, Facebook turned it down—for violating hate speech policies. “Your ad wasn’t approved because it doesn’t follow our Advertising Policies, which apply to an ad’s content, its audience and the destination it links to,” read the denial note Facebook sent Partridge. “We don’t allow ads that use profanity, or refer to the viewer’s attributes (ex: race, ethnicity, age, sexual orientation, name) or harass viewers.” A few things could have happened here. An algorithm could have second-guessed itself, which is not generally how computer programs work, or maybe one of the thousands of people who work on content moderation at Facebook decided in hindsight that the ad violated Facebook’s hate speech policy. Or perhaps someone from Patriot Prayer flagged the event ad as offensive—according to Partridge, the ad did run during those two hours, and he received a report that more than 200 people saw it.

Jamie Partridge

The Portland counterprotest was specifically rallying against bigotry of “Portland’s Immigrant, Muslim, Jewish, Indigenous, Black and LGBTQ+ communities,” as the anti-hate group wrote on its event page. When the Portland Stands United Against Hate organizers tried to appeal Facebook’s denial, they received no response. The only racial category described in any sort of potentially offensive way is “white nationalism,” a known term to describe people who organize under the idea that non-whites are inferior, which to be clear, is racism.

Facebook didn’t respond to Slate about why the ad was denied for violating Facebook’s hate speech policies, and the company’s full metric for how it decides what is and isn’t hate speech isn’t public. But in June, ProPublica published a report detailing leaked documents about Facebook’s content moderation policies. According to the documents, Facebook prohibits hate speech against “protected categories,” which include sex, race, religion, gender identity, national origin, serious disability or disease, and sexual orientation. But when it comes to hate speech directed at subsets of these categories, like age, political ideology, appearance, social class, or occupation, Facebook is far more permissive. According to ProPublica:

One document trains content reviewers on how to apply the company’s global hate speech algorithm. The slide identifies three groups: female drivers, black children and white men. It asks: Which group is protected from hate speech? The correct answer: white men.

So it seems likely that Facebook counted a rally against white nationalism to be racist against white people, and therefore banned the ad as a violation of its hate speech policies. Consider a post made by Louisiana Republican Rep. Clay Higgins following the London terrorist attack in June that called for the hunting and murdering of “radicalized” Muslim suspects, which was not removed from Facebook, as the ProPublica report highlighted. Yet just a few weeks earlier, a status update from Black Lives Matter activist Didi Delgado that dubbed “all white people” racist was removed, and her account was suspended for seven days. Higgins was referring to a particular subset of “radicalized” Muslims, whereas Delgado was criticizing white people in general.

Earlier this month, ProPublica also found that Facebook’s ad-buying system made it possible to target users interested in anti-Semitism. The investigation found that Facebook let advertisers buy ads that would reach “Jew haters” or people interested in “how to burn Jews.” Slate was able to find even more categories of user interests Facebook let advertisers target, like “killing bitches,” “threesome rape,” and “killing Haji.” So Facebook has let advertisers send ads to users based on their hatred of Jewish people and women, but wouldn’t let an anti-racist group promote their anti-hate March Against White Nationalism because it violated Facebook’s hate speech policies.

Last Wednesday, Sheryl Sandberg, chief operating officer at Facebook, posted a note to her Facebook wall that said the company is cracking down on its enforcement against ads that directly attack people based on race, sex, gender, national origin, religion, sexual orientation, or disability. She also wrote that Facebook plans to bring in more people to help with its content moderation and is building a new system to help users self-report complaints about ads, too. But it’s unclear whether any of these fixes will actually correct Facebook’s ad buying system, which is one of the primary ways Facebook, a company valued at more than $400 billion, makes its fortune.

Whatever Facebook decides to do here, more clarity and consistency will go a long way.