No one can dispute that there is sex trafficking in the United States, or that criminals now use the internet to facilitate sex trafficking and other crimes, just as they also use mobile phones and even the U.S. Postal Service. Make no mistake: Sex trafficking is reprehensible, and its perpetrators deserve to be punished to the fullest extent of the law.

But some members of Congress seem to believe the internet itself is to blame for sex trafficking. And they’re now trying to rush through legislation that would make it easier for state governments (as well as the federal government) to punish online service providers when criminals use their services.

That’s nuts. The internet we know and rely on today depends on a carefully balanced framework of laws that, by design, protect online service providers from being sued in every jurisdiction or prosecuted by every ambitious prosecutor who wants a headline.

Congress very deliberately set up this legal framework so that crimes on the internet—an inherently interjurisdictional medium—are primarily a federal matter. Currently, there are two basic federal laws that provide safe harbors to online platforms for content disseminated by their users. The Digital Millennium Copyright Act deals specifically with copyright infringement, while Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act generally addresses most other kinds of legal liability that service providers might routinely face. So, for example, YouTube wasn’t liable for copyright infringement when a user uploaded a video of a baby dancing to a Prince song on its site, and AOL wasn’t liable for any defamation when Matt Drudge republished a defamatory statement about Sidney Blumenthal on its site. This is as it should be: Individual perpetrators, not intermediary platforms, are usually the more appropriate targets.

This framework may not be perfect. For instance, there may be room for the DMCA’s notice-and-takedown provisions to be improved even if it generally gets the balance right. But these two laws help support and protect the innovative online ecosystem we have today. Neither the narrow provisions of the DMCA nor the broad protections of Section 230 offer platforms a blanket protection against prosecution or lawsuits. Importantly, Section 230’s liability protection does extend to federal criminal laws—including sex trafficking or conspiracies to facilitate criminal activity. But without the limited protections the DMCA and Section 230 provide, it’s likely that services like Wikipedia, Facebook, and Twitter wouldn’t exist. These laws are essential to making today’s robust online public squares possible, and they will likely be essential for the next generation of online entrepreneurs.

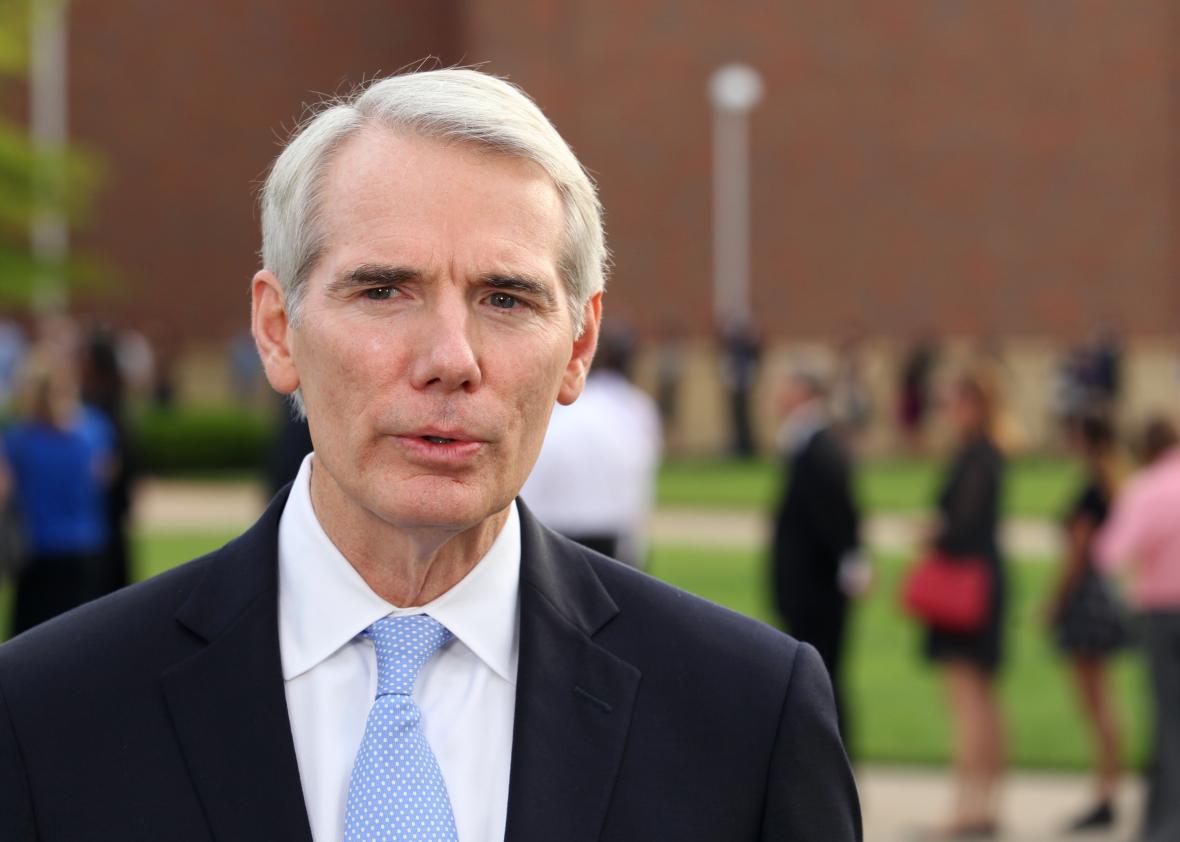

Yet now that entire online ecosystem is in danger. Sens. Rob Portman, R-Ohio, and Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., have recently introduced the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act of 2017 (S.1693), which would unravel Section 230 protections and to make platforms liable for being in the middle of sex-trafficking enterprises. SESTA’s sponsors have made clear they’re specifically going after Backpage.com and other internet classified-ad websites that some might use to market sex services.

But here’s the thing: the U.S. Justice Department already has the authority to investigate and prosecute them. They also can punish corporate online platforms when they cross the line. In fact, Portman has already asked the DOJ to do exactly that in the case of alleged wrongdoing by the online-classifieds service Backpage.com. Furthermore, SESTA’s language is so broad that it could lead to state lawsuits and prosecutions of sites that don’t carry any advertising at all. It could sweep in every online service that hosts user-generated content—perhaps even including email services and comments sections.

To draw an analogy, the bill would be as if Congress decided that FedEx was legally liable for anything illegal it ever carries, even where it’s ignorant of the infraction and acts in good faith. That would be a crazy notion in itself, but rather than applying only to FedEx’s tech equivalents—the giants like Google and Facebook—it also would apply to smaller, less well-moneyed services like Wikipedia. Even if the larger internet companies can bear the burden of defending against a vastly increased number of prosecutions and lawsuits—and that’s by no means certain—it would be fatal for smaller companies and startups. Amending Section 230’s broad liability protection for internet service providers would expand the scope of criminal and civil liability for those services in ways that would force the tech companies to drastically alter or eliminate features that users have come to rely on. It could strangle many internet startups in their cribs.

SESTA’s co-sponsors—who also include Sens. John McCain, R-Ariz.; Claire McCaskill, D-Mo.; and Ted Cruz, R-Texas, among others—are rumored to be attempting to push the bill through quickly without the kinds of hearings and evidence-gathering that ought to be afforded to an issue of this magnitude and complexity.* It has been suggested that SESTA could be attached to the National Defense Authorization Act, a large “must-pass” funding bill for the U.S. Defense Department. For this to happen, it would have to go through McCain, who chairs the Senate Armed Services Committee. He may be a co-sponsor of the legislation, but let’s hope the maverick sticks with his laudable talk of returning to regular order—and this overly broad bill is subjected to the greater consideration and scrutiny it deserves under the normal committee process.

I’m not saying Congress shouldn’t consider laws—including potentially amending Section 230—that would improve the prosecution of sex trafficking and better protect children from sexual abuse. But we need to update those laws in thoughtful ways that also safeguard the internet on which we’ve grown to rely. Both the substance and process for this legislation drastically falls short of the kind of reasoned balancing of interests we have every right to expect from Congress. Worse, it could hobble the fast-paced economic and personal benefits we expect and hope for from the internet. When we think about protecting our children, we need to think about saving the internet for them, too.

*Correction, Aug. 28, 2017: This post originally misstated what state Sen. Claire McCaskill represents. It’s Missouri, not Connecticut.