The Federal Trade Commission received a complaint Monday from privacy advocates requesting a full investigation into a new advertising scheme from Google that links individuals’ online browsing data and what they buy offline in stores.

The privacy group that launched the federal complaint, the Electronic Privacy Information Center, alleges that Google is using credit card data to track whether online ads lead to in-store purchases without providing an easy opt-out or clear information about how the system works. The complaint specifically calls out a new advertising program Google unveiled in May that reportedly relies on billions of credit card records, which are matched to data on what ads people click on when logged into Google services.

The ability to link online ads to actual in-store purchases is often described as the “holy grail” of data-driven advertising, according to David Carroll, a professor at the New School who studies the online data tracking industry.

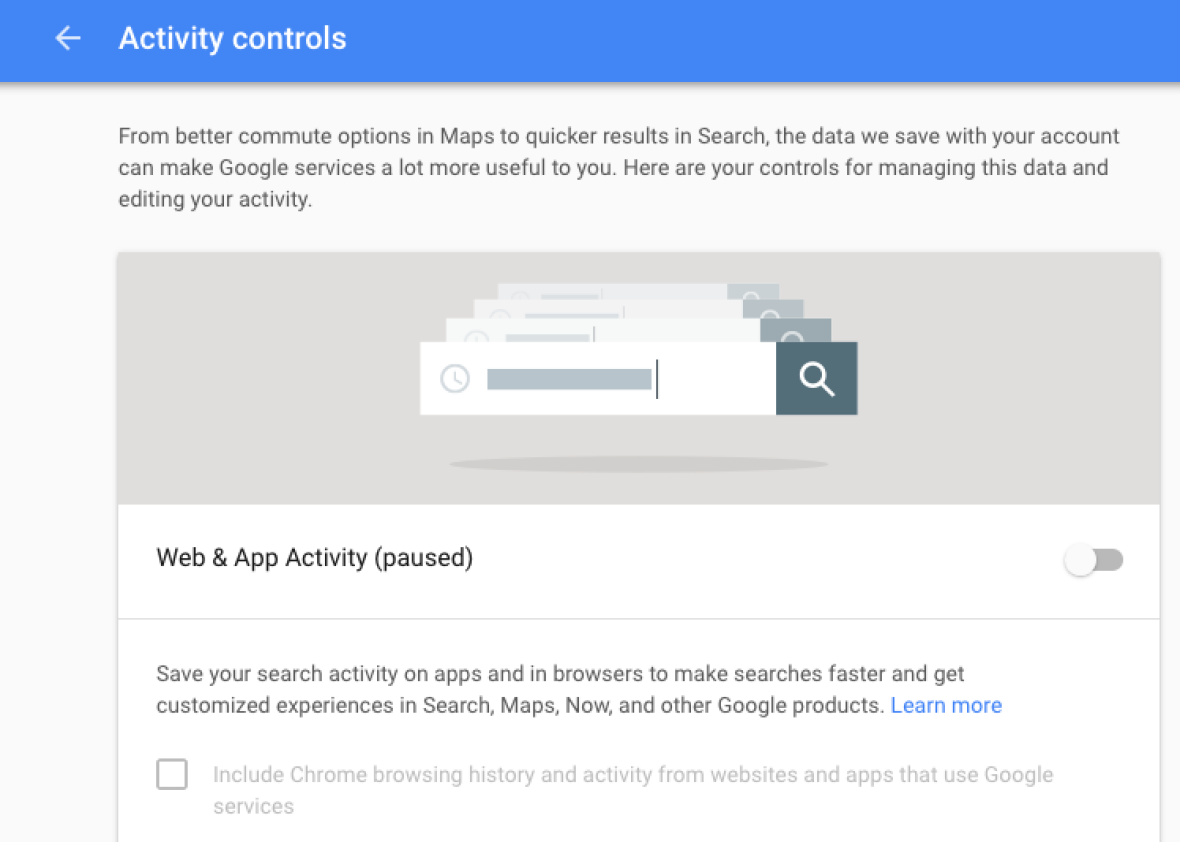

Google says it can’t disclose which companies it works with to get customers’ offline shopping records because of confidentiality agreements it has with those partners. So at the moment, the only way for a Google user to prevent his or her offline purchasing history from being linked to their web browsing is to opt out of Google’s web and app tracking entirely, which could make it nigh-impossible to use other Google services.

If Google did share the names of its partners in its offline ad-tracking program, customers could presumably stop using those services. There are plenty of reasons why a person wouldn’t want their offline purchasing data to mingle with their online accounts. What you buy at a drug store alone can point to health concerns, sexual history, or other personal information that you may want to keep to yourself.

But Google says not to worry about that information seeping out, since it “does not learn what was actually purchased by any individual person (either the product or the amount). We just learn the number of transactions and total value of all purchases in a time period, aggregated to protect privacy,” a spokesperson said in an email. In other words, Google is saying that the advertiser doesn’t learn who clicked on their ads, just how many of those clicks translated to offline sales.

But that even if the data is anonymized by both credit card payment data holders and Google, those in-store linkages are not truly anonymous, despite what companies claim, according to Chris Hoofnagle, a law professor at Berkeley who specializes in data privacy.

“There’s a long history to this,” Hoofnagle said. Ten years ago, a digital advertiser industry group, the Data and Marketing Association, argued that phone numbers were not personally identifiable information since one number is usually shared within a single household linked to multiple individuals. That logic is being recycled. Hoofnagle says that digital marketers’ “new trick is to take personally identifiable information and hash it.” That means the personal data is encrypted. “That would be fine,” Hoofnagle continued, “but everyone uses the same hashes, and so these hashes are essentially pseudonyms.” Or, as Wolfie Christl, a digital privacy researcher and author of the book Networks of Control, explains in a recent report, data companies generally use the same encryption method. If everyone is masked with the same pseudonym process, it’s easy to track that pseudonym across the internet

Just last week, at the annual hacker conference Defcon in Las Vegas, a journalist and a data scientist shared how they were able to obtain a database tracking 3 million German users’ browsing history, spanning 9 million different websites. The data set was said to be anonymized, but the team was able to de-anonymize many of the users, according to a report in the Guardian. For some people, the researchers could just look at the browsing history. For instance, a Twitter analytics page contains a URL with the username in it—so checking to see if a tweet went viral could give away your identity in “anonymous” browsing data.

EPIC’s complaint also points out that Google isn’t sharing enough detail about how it’s encrypting the data. The complaint alleges Googles uses a type of encryption, CryptDB, that has known security flaws. While it’s unclear that Google’s offline to online ad-tracking system uses CryptDB, Google has not shared details on the math and software that its using to implement its encryption.

“We don’t know a lot about how this is implemented,” said Joseph Lorenzo Hall, a technologist with the Center for Democracy and Technology, which is in part funded by Google. Hall says that typically Google would publish a white paper or some further explanation of how its encryption works.

Google also wouldn’t clarify whether users consent to having their web browsing linked to their offline purchase history, but a spokesperson did say that their “payment partners have the rights necessary to use this data.”

Carroll of the New School says that Google’s ad practices here can be manipulative. “Google is in the market of predicting consumer behavior and commoditizing our behavior at scale,” said Carroll. “We don’t know how it works. We don’t know how they are protecting us.”

Even if Google is able to anonymize its ad data, it should still make it easier for people to opt out of linking their browsing history to their offline shopping. Right now, you have to go navigate to the privacy settings of your account and then find the Activity Controls page.

It’s not super intuitive to find, but then again, Google, which is in the business of selling ads, would probably prefer you keep your personal data as accessible as possible.