In 2014, when the Justice Department charged five members of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army with illegal cyberespionage, the New York Times called the move “almost certainly symbolic since there is virtually no chance that the Chinese would turn over the five People’s Liberation Army members named in the indictment.” Indeed, nearly three years later, those charges have led to no arrests and, seemingly, has done little more than irritate the Chinese government.

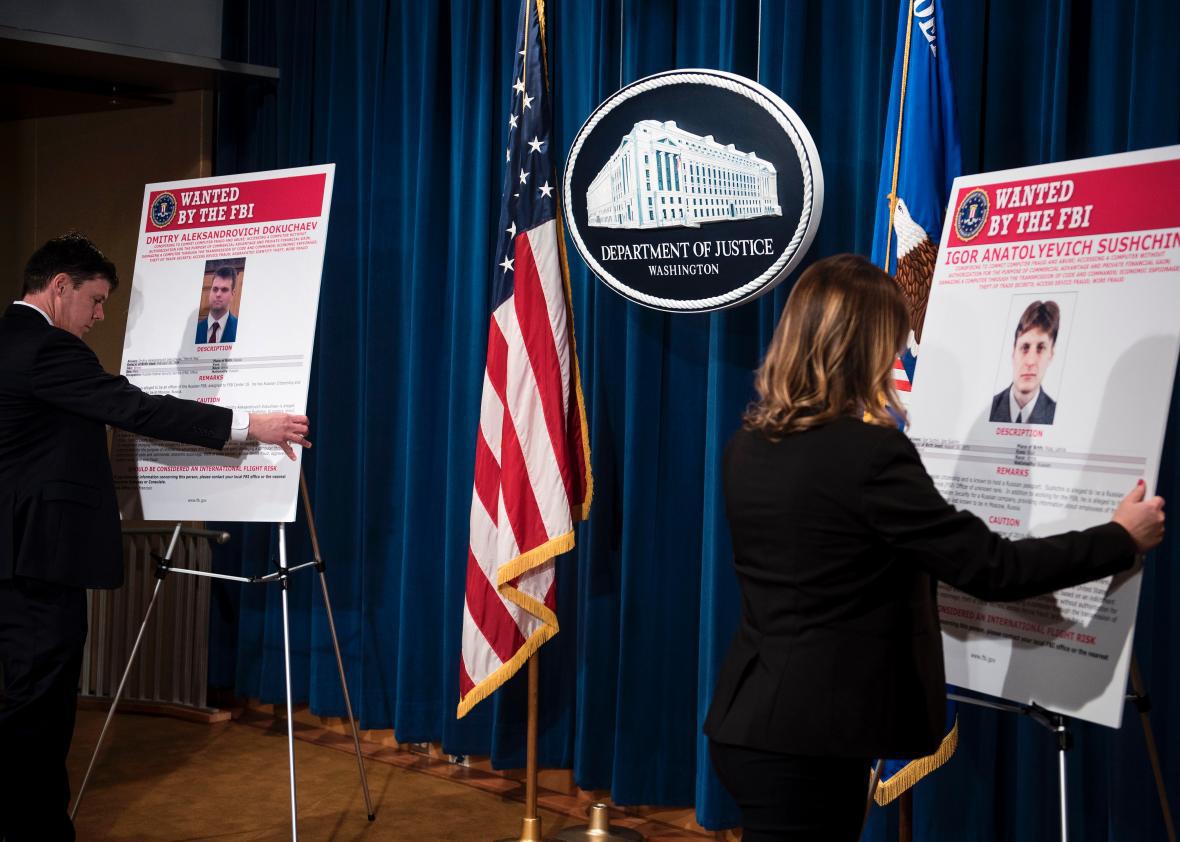

The Justice Department’s decision this week to charge two members of the Russian Federal Security Service with similar cyber espionage crimes—tied, in this case, to the 2014 breach of millions of Yahoo user accounts—appears, at first glance, to be similarly symbolic. The traditional legal toolset for enforcing laws—indictments, trials, juries, imprisonment—are not especially useful when it comes to going after people who are living in other countries and are protected by (indeed, in these cases, employed by) their home governments. The United States can file as many furious indictments as it likes against the members of foreign intelligence services who have infiltrated U.S. computer systems, but the FBI Wanted posters are unlikely to deter those services from doing their jobs.

Still, this week’s charges against the Russians may be slightly more meaningful and less symbolic than those against the Chinese for two reasons.

First, the newly released charges actually resulted in an arrest—not of either of the two charged FSB officers but of independent hacker Karim Baratov, who allegedly helped the FSB infiltrate Yahoo’s networks and who, inconveniently for him, lived in Canada. The two FSB officers named in the indictment, Dmitry Dokuchaev and Igor Sushchin, and the other independent hacker charged with helping them, Alexsey Belan, all live in Russia and have not been arrested. They probably never will be. But even being able to try one person for complicity in a foreign government’s cyberespionage efforts would be a triumph both because it might actually help deter others from following the same path and, perhaps more likely, the trial could offer even greater insight into the inner workings of Russia’s cyber operation.

Second, the the indictment filed against Dokuchaev, Sushchin, Belan, and Baratov gives the rather remarkable impression that arrest and prosecution was not necessarily even the Justice Department’s endgame. Instead, the details of the Yahoo breach laid out in the document seem designed to embarrass the four accused men, perhaps even get them in trouble with their own employer—and to spread distrust of the FSB within Russia and neighboring countries.

The indictment details how the accused allegedly tried to use their compromise of Yahoo’s networks to enrich themselves, not just to provide useful intelligence to the Russian government. For instance, according to the indictment, Belan hijacked Yahoo searches for erectile dysfunction drugs so that people who searched for them would be redirected to the website of an online pharmaceutical company that would, in turn, pay Belan for sending traffic its way. The indictment also accuses Belan of searching compromised Yahoo email accounts for retail gift cards and credit card information. And no surprise he was trying to supplement his income since the FSB’s freelancing fee, per the indictment, is roughly $100 per targeted compromised account.

While much of the indictment covers the compromise of accounts run by U.S. companies, including Google as well as Yahoo, the actual espionage activities it details are largely unrelated to U.S. targets. For instance, their targets apparently included officers of a Russian financial firm, an assistant to the deputy chairman of the Russian Federation, the chairman of a Russian Federation Council committee, a physical training expert employed by the Ministry of Sports of a Russian republic, the CEO of a metals industry holding company in a country bordering Russia, a prominent banker and university trustee in a country bordering Russia, an International Monetary Fund official, employees at a major Russian cybersecurity firm, and an officer of the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs working in its “Bureau of Special Technical Projects” (which, coincidentally, investigates “cyber, high technology, and child pornography crimes”).

The indictment doesn’t name any specific victims or compromised email accounts but it does offer some largely redacted examples of targeted accounts (******as@gmail.com, for instance, as well as ********ov@yahoo.com and ************va@gmail.com). I can only imagine these were included in an effort to send into a panic every person in Russia (and its neighboring countries) with a last name ending in –va, –ov, or –as.

Indeed, much of the indictment seems to have been written to incite discord and distrust of the FSB by Russian companies and government officials. On the flip side, it could serve as a warning to the FSB that its freelancers are using their assignments not just to gather the requested information but also to pick up a few stolen gift cards and redirect some unwitting online shoppers just trying to find a reputable place to buy their male enhancement drugs. Hopefully, it will also make Russians a little more wary of emails purporting to be from the Russian Federal Tax Service (a phishing technique employed by Sushchin and Dokuchaev to try to compromise accounts of Russian financial officers).

Whether any of that will matter to the Russian government is anybody’s guess, but it’s an interesting way to try to make what would otherwise be a fairly toothless indictment a bit sharper. Rather than a tool of legal process, this indictment reads more as a reminder that the U.S. government can also reveal embarrassing information about the inner workings of the Russian government, even if it can’t get its hands on the men who stole your Amazon gift card.