I was part of the “Oregon Trail Generation,” which means that as a child I spent a lot of time dying of dysentery. The first computer I remember was my family’s IBM PC, which I mostly used for playing Maniac Mansion from a copied floppy disk before anyone realized that software piracy was a thing.

At that point, using a computer was not a social activity, except for when we played Oregon Trail at school, named characters after one another, and pointed and laughed when they were bitten by snakes. You didn’t turn to a computer to read things or find information, until the amazing invention of encyclopedias on CD-ROM, invaluable for writing reports about Peru and the Battle of Gettysburg and Odysseus.

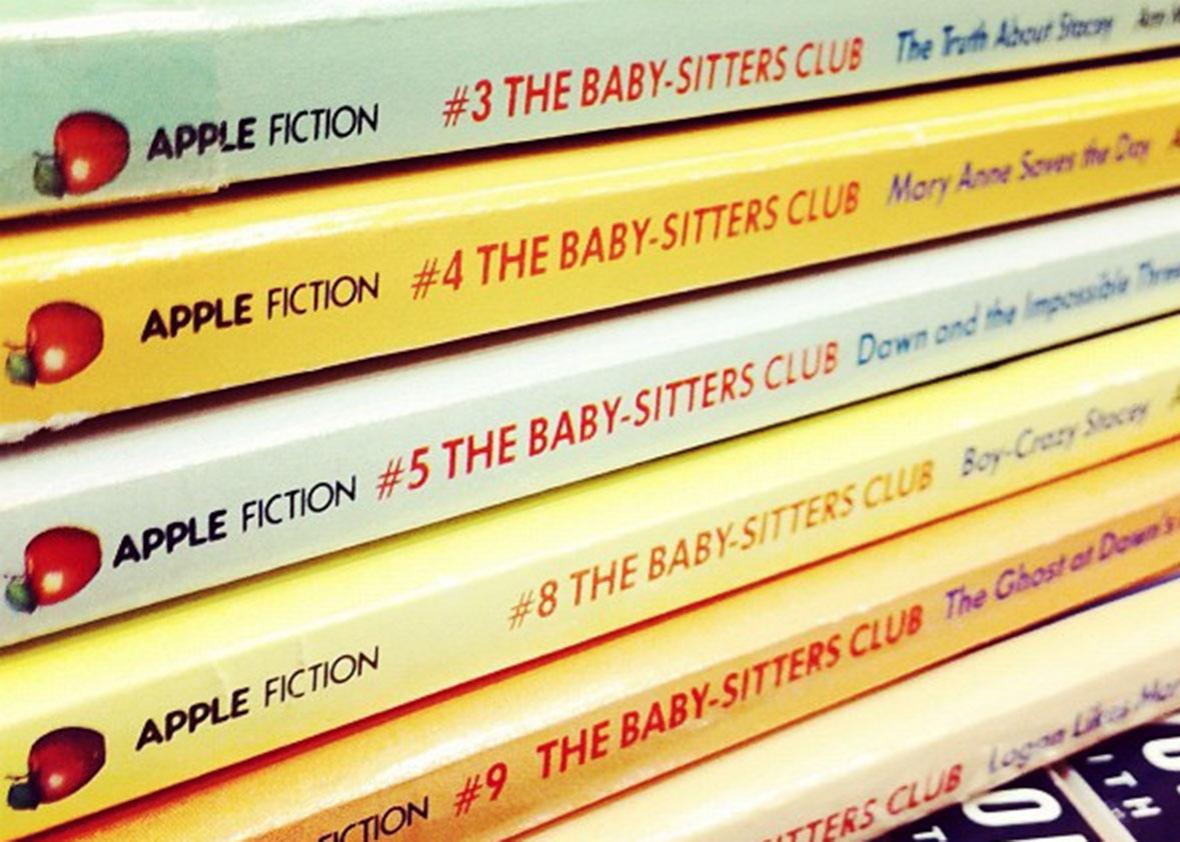

So before Tumblr and Reddit were even a twinkle in their creators’ eyes, I spent elementary school devouring books at a good clip. My parents eventually started trying to nudge my reading habits in productive directions. They bought me Black Beauty and Treasure Island and Little Women. I would read them and enjoy them, and then get back to stacks of Sweet Valley High and Baby-Sitters Club. I also read Gone With the Wind when I was 9 because someone told me I couldn’t, and I decided I preferred Sweet Valley, California, and Stoneybrook, Connecticut, over the Deep South.

The Baby-Sitters Club books were particularly engaging for me because I was so enamored of the idea of a close group of friends. My family moved twice while I was in school, and it always took me a while to make new friends. What I really, desperately wanted was someone to talk to about books. I wanted a book club! And the friends that I did make never seemed to be interested in the books I liked. In the early ’90s it seemed like all preteens wanted to read was R.L. Stine, but reading a single book about evil cheerleaders gave me my first experience of literary snobbery. (I once tried to convince someone that A Wrinkle in Time was a horror novel. It didn’t work.)

It’s probably appropriate, then, that it was the Baby-Sitters Club that first taught me that a computer could be used for talking to people. Specifically, it was back-of-the-book ad for Prodigy, declaring boldly that with the new Online Baby-Sitters Club, you could talk to Ann M. Martin and read brand new stories and make friends all across the country! Whoever created this “online” thing, I immediately decided, was speaking directly to my soul. For some time after that, I assumed the internet was just a place where people went to talk about Baby-Sitters Club, which seemed like a pretty worthy invention to me.

Obviously I begged my parents for Prodigy. This was 1992, and they had no idea what I was talking about. In retrospect, I can understand why $9.95 per month for five hours of online time for me to talk about books with strangers might have been a hard sell. They didn’t sign up for Prodigy.

I reached out to Ann M. Martin to see if she had fond memories of the Prodigy board, though it turns out that, though she wrote content for the board, she had little to do with the Internet aspect and didn’t communicate directly with participants. Still, exchanging an email with Ann may have just made my dashed childhood dreams finally come true.

My first online experience came a couple of years later when a middle school friend’s dad set up a bulletin board system. We would log in after school and send messages to each other and play Legend of the Red Dragon. My seventh-grade diary recounts in great detail how the boy I had a crush on asked my in-game character to marry him, followed by by agonized speculation about what it meant. To this day, it remains a universal constant that most new technologies can be immediately appropriated for middle-school flirting.

Of course, it was my family’s subscription to AOL when I was 14 that really opened up the world to what I knew it could be—something beyond the local. I didn’t have to force my friends to read the things I wanted to read. Instead, I could find people literally anywhere to talk to about J.R.R. Tolkien and Danielle Steele (since at that point I was beyond Baby-Sitters Club … OK, fine, I was also reading Sweet Valley University). And thanks to Usenet, I also discovered that when I’d been writing my own stories about Kristy, Mary-Ann, Claudia, and Stacey (or, more recently, Kirk and Spock), it was actually a thing called fan fiction, and that other people did it, too, and then shared it with each other!

At some point during college when I realized that I could study the internet for a living. Many years later, I’m doing exactly that, and sometimes I’m struck by how much we can focus on the negative and take for granted how much smaller and lonelier our worlds might be if we weren’t online. We might see more of the bad things in the world than we’d like to see, or we might learn too much about our friends’ political beliefs, or we might suffer the worst kind of context collapse when our high-school acquaintances fight with our bosses in Facebook comments.

We may also spend less time with our noses in books than we might if our eyes were never on a screen, but we also always have someone to talk to about them afterward. And when the outside world is a bit more contentious, and our friends are about to be bitten by snakes, we can gather online to help them—now, no one has to travel the Oregon Trail alone.