Watching a recent trailer for the forthcoming Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, I caught a brief glimpse of an old-fashioned control panel, its huge, brightly lit buttons shining out against the imperial dark. For all the familiar futuristic trappings of the surrounding shots, that one image is immediately recognizable as the residue of an older fantasy. It is a trace not just of the earlier films in the series but also of the moments in which those films were made, evidence of a way we once imagined the world could someday be.

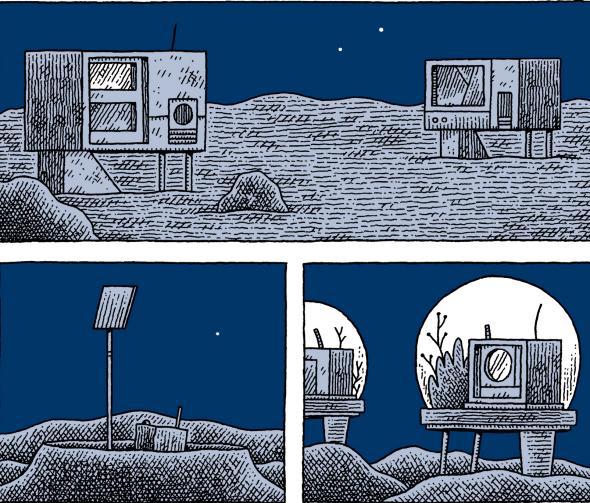

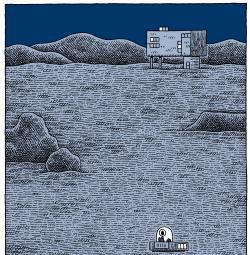

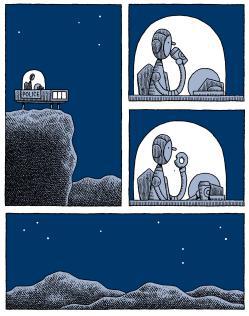

As I contemplated that shot, I found myself pulled back to Tom Gauld’s recent comic book, Mooncop. At once poignant and quietly comical, Gauld’s short novel, published in September, follows an unnamed police officer while he goes about his business during a peaceful lunar colony’s final days. Everything has an oddly outmoded quality, from the modular modernist buildings—which look like Le Corbusier dwellings as interpreted by NASA—to the fishbowl glass helmets people wear in place of more functional spacesuits. There’s no crime to solve, his therapist robot is on the fritz, and the satellite’s population is dwindling as the colonists give up and return to Earth, leaving him increasingly alone among its washed-out craters and crags. This is an earlier idea of the future, one that’s already largely been forgotten when it failed to line up with the unfolding present.

Tom Gauld/Drawn & Quarterly

Over email, Gauld told me that he’d gone back into his own past to find inspiration for the book. “I was thinking of the science fiction I ingested as a child and which, at the time, I perhaps didn’t entirely realize was fiction,” he wrote. More recently, he recalls seeing “a 1960s tin toy of a silver moon patrol police car with a figure driving from within a glass dome,” a reminder, as he puts it, that we once imagined “not only that we would colonize the Moon but that it would be so successful that we’d need a police force up there to maintain order.” Yet the box of that same toy showed the officer surveilling an empty lunar landscape: Much like the hero of the book Gauld would eventually write, the officer was patrolling just to patrol.

Gauld’s most resonant themes here are disconnection and isolation. In one elegant, melancholy sequence, our protagonist observes the distant Earth from a lunar bluff, watching enormous clouds kiss the continents. “It seems like the party’s over and everybody’s going home,” he complains later. That lament vibrates throughout the surrounding pages: A few notable exceptions aside, he is almost always the only character in any given panel. When others join him, he still typically stands apart, secure and distant in the glass bubble of his space helmet.

Tom Gauld/Drawn & Quarterly

Even the most dogged residents of Gauld’s moon aren’t quite sure why they’re doing on its inhospitable surface. “Whatever were we thinking? It seems rather silly now,” one of the earliest colonists wonders aloud, shortly before departing. Silly is exactly the right word: Despite the somber blue and gray shades of Gauld’s art, Mooncop’s tone is much like that of the science fiction he enjoyed as a child—“hopelessly naive, but often sweetly so,” as he puts it.

Of course, such naiveté isn’t always a design choice, just as it isn’t always sweet. In ways Gauld couldn’t have anticipated while working on the book, it’s tempting to read it in dialogue with Donald Trump’s anti-scientific agenda. At least one of the president elect’s advisers has suggested that the incoming administration plans to abandon NASA’s climate change research, and instead pump funds into space exploration. As with most of Trump’s nebulously-defined goals, that plan has more to with re-creating past glories—Space Age triumphs, in this case—than it does with building a better, more livable, tomorrow. He would rather reconstruct an obsolete vision of the future than protect against imminent threats in the present.

On a too facile reading, Mooncop’s retrofuturistic style might seem to align Gauld’s work with Trump’s perverse rejection of immediate, terrestrial realities. Like the aesthetics of Star Wars—aesthetics that inspired some of Gauld’s own design choices—this is a dream that we cling to, even as the waking world chips away at it. Ultimately, though, Mooncop instead revels in the persistent promise of possibilities that never quite found their way into the waking world. It hollows out a space within those evacuated visions and invites us to live within.

Mooncop, in other words, makes poetry from the act of dwelling on what could have been, however improbable it might seem in retrospect. This is a story about recommitting to dreams that others have abandoned. If Mooncop is a lonely book, it’s likely because dreaming is lonely work, even when we struggle—as Gauld’s hero ultimately does—to dream together. But as Gauld shows, the very effort can also be surprisingly beautiful.