Late-night overdrinking? Writer’s cramp? Spoiled kids? Such complaints haunted 19th-century Britons. The blog Diseases of Modern Life is run by a group of historians at the University of Oxford, working on a research project about Victorians who feared that new technologies and configurations of social life were making people sick. The body and the world—such commentators thought—had fallen tragically out of sync with one another, in an industrial age of telegram and train travel.

This blog is full of fascinating tidbits the researchers have come across in the course of their investigations. (It’s also got great images, some of which I’ve reproduced here.) There are some delicious oddities: In one post, researcher Melissa Dickson describes the ammoniaphone, a creation of a Dr. Carter Moffat, who claimed to take the air of southern Italy, which (opinion agreed) produced the best opera singers, and distil it into a chemical formula that you could huff in order to purify and clarify your voice. Here was a technological solution to rampant air pollution, branded and packaged to offer immediate relief.

Science Museum, London. Wellcome Images

In another post, Dickson writes about H.G. Wells’ short story “The New Accelerator,” from 1901, about a chemist who creates a “nervous stimulant” that would let a person move so quickly that he could perform all of his duties at warp speed, thereby defeating the demands of a world that came at you too quickly. This satire argued that the only way a person could possibly keep up with the rush of modern life was to become superhuman.

In many a case that the researchers identify, Victorian ideas about “diseases of modern life” seem to be totally intertwined with ideas about class and social place. Jennifer Wallis analyzes widely circulated stories about new kinds of addiction and intoxication: lady cologne drinkers, who supposedly hid their alcoholism by chugging perfume; lawyers and clerks and other professional men who imbibed alcohol late at night, not at the pub but in their own offices; the well-to-do woman supposedly “picked up on Broadway,” having succumbed to a morphine addiction. (That last lady appeared in an advertisement for Lydia E. Pinkham’s patent medicine, which she should have turned to instead.) In all of these cases, people who were socially expected to control themselves in every situation were driven to drink by the hectic pace of their work and social lives.

The consequences of such a world for the young were supposed to be dire. In another post, Wallis writes about fears of overpampered or “spoiled” children, who would not eat what they were served and rampaged through their family houses without censorship from “indulgent” parents. “Nineteenth-century concerns for spoiled children drew on contemporary ideas about the development of the nervous system and laws of heredity, considering how the process of growing up might literally—and permanently—alter the fabric of the body and brain,” Wallis writes. (Here’s a fine contemporary joke from the London Journal: “There’s one good thing about spoiled children.” “What’s that?” “One never has them in one’s own house.”)

Diseases of Modern Life

Well-to-do late-19th-century women brought flower arrangements into the drab, ugly houses of poor people who were stricken with illnesses, believing that the beauty of the flowers could cure any number of ills. While this idea now seems eminently condescending—surely the stricken poor might prefer deliveries of food for the rest of their family members to eat?—Wallis points out that no less an authority than Florence Nightingale believed in the practice, writing in her Notes on Nursing:

The effect in sickness of beautiful objects … and especially of the brilliancy of color is hardly at all appreciated. … Little as we know about the ways in which we are affected by form, by colour, and by light, we do know this, that they have an actual physical effect.

In offering this “cure,” “flower missionaries” thought to bring a little bit of nature to people who were totally trapped inside the urban cityscape industrialism had created.

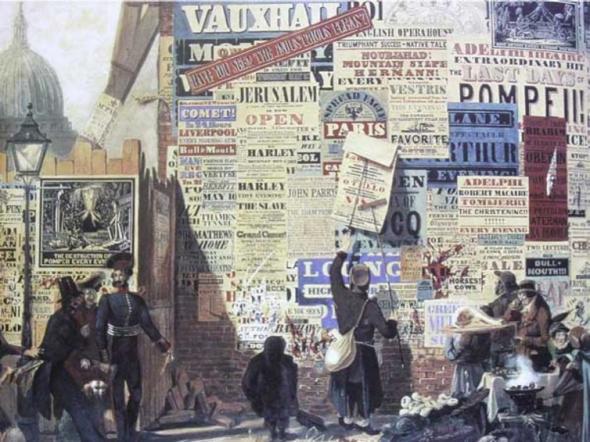

Sometimes, the poor were recast as just part of a threatening landscape of urban ruckus, which encroached on the tranquility of the well-to-do class. Furious at the impositions of street musicians, who made it impossible for them to get work done in the city, in 1864 a group including Charles Dickens petitioned the House of Commons to pass a Bill for the Suppression of Street Music. “Your correspondents are professors and practitioners of one or other of the Arts of Sciences. In their devotion to their pursuits … they are daily interrupted, harassed, worried, wearied, and driven nearly mad by street musicians,” the group wrote. The petitioners cared far less for the conditions that might have driven the musicians into such a job, and more for their own peace of mind.

Is it helpful for us, contemplating our own “Diseases of Modern Life”—depression, anxiety, digital distraction, overwork—to know that people have been thinking roughly recognizable thoughts for hundreds of years?

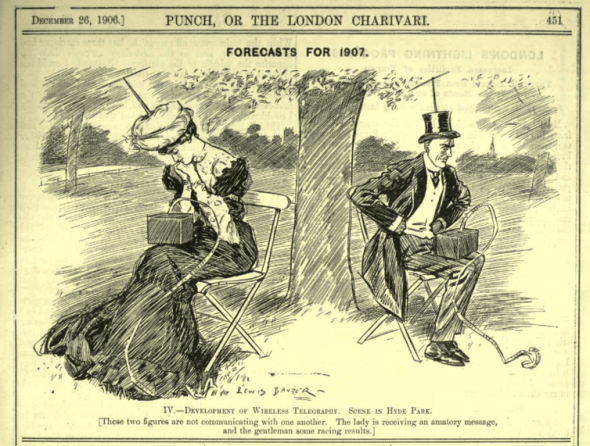

Internet Archive

Writing about a cartoon that appeared in Punch in 1906, Melissa Dickson notes the similarity between this satirical scene—a man and a woman, each with their separate wireless telegraph—and today’s worries about smartphone alienation: “Different technology, same statement … As dramatically as technology changes, we, at least in the way we regard it, remain surprisingly unchanged.”

But I find it more helpful to think in terms of precursors. It’s not that “nothing has changed,” and so none of our contemporary concerns are valid. It’s more that the social world we live in has been rapidly evolving in response to an explosion in new technologies for at least two centuries. The value lies in thinking critically about the way these anxieties take shape. How many of today’s middle- and upper-class concerns about “Today’s World” would look just as class-bound as the Victorians’ dated worries, if examined from a vantage point of a hundred and fifty years hence?