Early this week, James Clapper, the head of U.S. intelligence, complained to journalists that Edward Snowden’s whistleblowing (my word, not Clapper’s) had sped up wider use of encryption by seven years. That’s great. Now let’s speed it up even more.

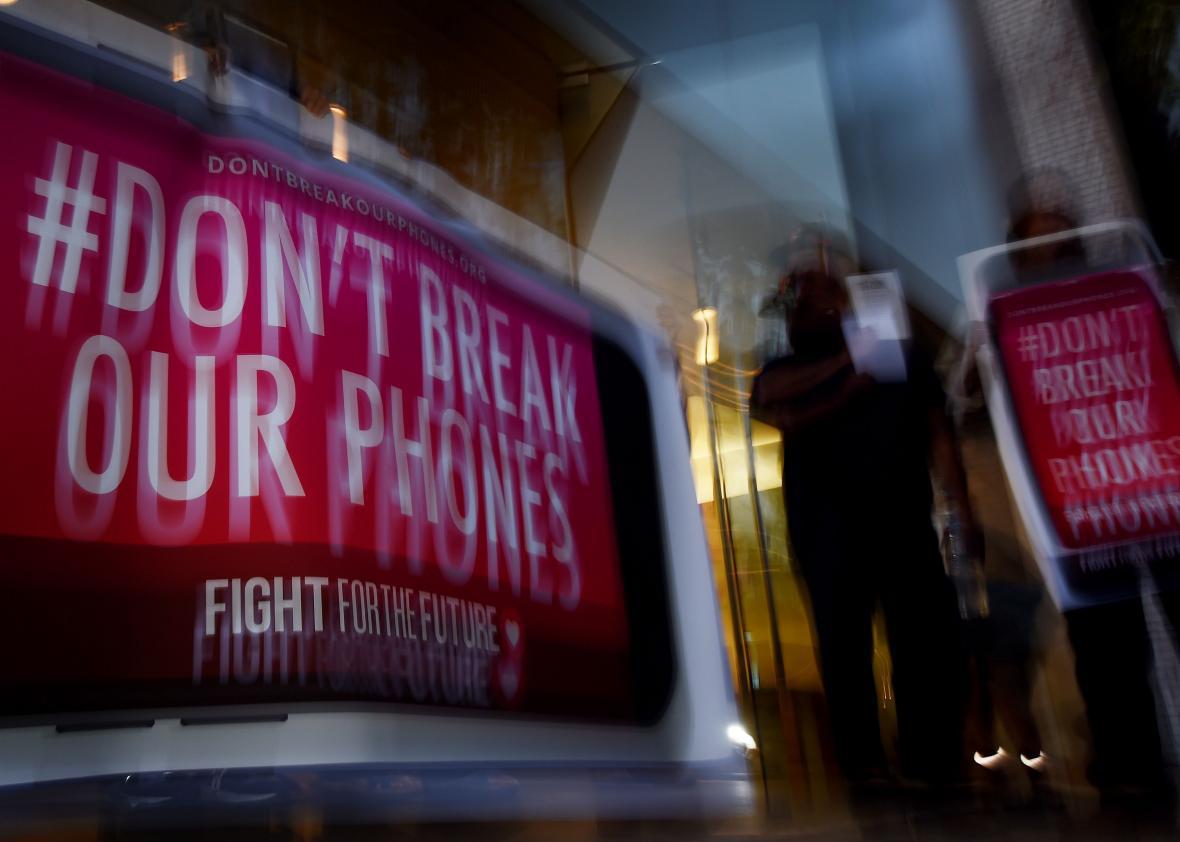

Not so fast, of course. Lots of powerful people don’t just want to hinder the adoption of strong encryption. They actively want to derail it.

Which is why, in several recent cases involving Apple phones, the FBI appealed not just to a judge but to public opinion. It warned that national security depended on being able to crack the late San Bernardino killer’s employer-supplied phone. Then it paid hackers more than $1 million to find a flaw in Apple’s operating system. It demanded access to another phone in New York state, but got access in other ways to the passcode. These cases went away, but not the issues they raised.

Law enforcement has only escalated its fear-mongering about going dark—being unable, due to strong encryption, to understand what surveillance targets are saying to one another or decipher the data on their devices. Members of Congress are proposing new legislation that would require tech companies to compromise the security of devices and software. The 1990s “Crypto War” over mobile phones is being replayed with new ferocity, this time in a much larger arena. The rhetoric has inflated commensurately.

The specter of terrorists communicating freely may have been the government’s ace in the Apple case. But it’s hardly the only card that people in authority can play. And we’re seeing the outlines of their strategy as the nation finally starts to debate what is truly a binary issue.

Encryption is binary because it’s either strong or it isn’t. A backdoor makes it weak. The experts in the field are clear on this: Weak or crippled encryption is the same thing as no encryption. So the choice we’re going to make as a society is whether we can securely communicate and store our information, or whether we cannot.

Those of us who believe we must protect strong encryption have to acknowledge some potentially unpleasant realities if our side wins this debate. If you and I can protect our conversations and data, so can some very bad people.

President Obama foreshadowed the next phase of the crypto fight in Austin last month. Speaking at the South by Southwest conference, he talked about, among other horribles, a “Swiss bank account in your phone” that strong encryption might create.

Consider the banksters who rigged interest rates, stealing billions from the financial system and eroding yet more trust in our vital institutions. They were caught because they were brazen and stupid in their communications, which provided evidence of their conspiracy. Do we want to make life easier for corporate criminals? (Of course, given our government’s notoriously soft-on-corporate-crime stance in recent years, at some level impunity already is the default.)

Do we want public officials to have easy ways to violate open-government laws? In many states, for example, members of city councils are required in most circumstances to communicate in ways that will leave a public record. Should we effectively invite the venal ones to cheat?

That latter scenario resonates with me for many of reasons, including this: I’m on the board of the California-based First Amendment Coalition, which fights for free speech and open records. I can’t be specific, but we’re currently involved in a case featuring members of a city council whose email communications are being withheld from the public. What happens when—not if—they take these to Signal, a text-messaging and voice system that encrypts everything, or to PGP-encrypted email, where even if we get the records we won’t be able to read them?

Given these potential problems, it’s tempting to be sympathetic with the law enforcement position on encryption—but history is clear that we can’t trust the government in this arena. As Harvard law professor Yochai Benkler wrote recently, our law enforcement and national security institutions have routinely—and with the impunity so routinely assumed by the rich and powerful—lied, broken laws, and thwarted oversight. “Without commitment by the federal government to be transparent and accountable under institutions that function effectively, users will escape to technology,” he wrote, and as a result we are learning to depend on technology.

Which also means, in the absence of remotely trustworthy government, we’re going to have to be honest with ourselves about the potential harms to transparency and accountability in a strong-crypto world. Yes, some tools make it easier to commit crimes. Yes, the Bill of Rights (or what’s left of it) makes things less convenient for the police. Yes, we take more risks to have more liberty; that’s the crucial bargain we struck with ourselves at the nation’s founding.

As Oregon Sen. Ron Wyden explained at a recent gathering of technology and human rights activists, it would be much more dangerous to force backdoors or other crippling of technology. And as he said in response to truly idiotic anti-security legislation from two powerful senators, “it will not make us safer from terrorists or other threats. Bad actors will continue to have access to encryption, from hundreds of sources overseas. [And it] will empower repressive regimes to enact similar laws and crack down on persecuted minorities around the world.”

As so many others have said, this is not about security vs. privacy. It is about security versus a lack of security—for all of us. That’s going to cause some discomfort, but liberty has a way of doing that.